In February 2022 a Nor’easter blew into Maine and toppled a 100-year-old apple tree on Ben and Laura Herman’s farm. The four movements that follow tell the story of Bruce Herman’s affection for that tree.

I

Eleven years before the tree’s demise, Bruce photographed his grandson, Will, Ben and Laura Herman’s son, perched in its upper limbs. One year later that image inspired a new painting, QU4RTETS No. 1 (Spring). Together with three more of Bruce’s figurative works, four minimalist paintings by Makoto Fujimura, and an original musical score by Yale composer Christopher Theofanidis, No.1 (Spring) became part of called QU4RTETS—a collaborative endeavor to celebrate T. S. Eliot’s long poem, Four Quartets.[1]

When Bruce begins a painting, he lays down a ground of pigment on a prepared panel to which he often applies squares of gold or silver leaf. Passages of scumbled opaque paint follow. He also abrades his surfaces, scrapping away paint or using a sander to reveal hidden layers of color and texture. Layers of varnish or alkyd resin are added to finish the work.

Each Herman painting in the QU4RTETS collaboration represents one of the four seasons. For instance, the lower lefthand corner of No.1 (Spring) features patches of chartreuse, green, and paired with passages of light cobalt blue above, this pallete signals spring. I am reminded of the words of Wendell Berry that read “Where the winter lay dead-brown/on the wood’s floor, now green/leaves and flowers open/and flourish in unconditional being . . .”[2]

The central figure in No.1 (Spring) is a semi-abstract rendering of the apple tree. Yet as we follow the rise of its thick trunk upward it reaches a barefooted boy. Above his head is a rectangle of moon gold that to my mind looks like an eight-light window to heaven. Wearing a white T-shirt and cut-off jeans with knees pulled slightly toward his chest and left arm resting on another tree limb, he appears comfortably settled in the crotch of the tree. Will’s head is turned directly toward us. Eyes alert, he surveys the world and he studies us.

The fourth section of Four Quartets, “Little Gidding,” contains this line, “. . . the children in the apple-tree.” For Eliot, it may be that the apple tree gestures Eden and the children, Adam and Eve, its prelapsarian innocents. But like Herman, Eliot surely knew that the tree of the knowledge of good and evil mentioned in Genesis was not an apple tree, that only legend. Better the “apple tree among trees of the wood” mentioned in Song of Solomon 2:3, thought by many to prefigure Christ, as sung about in the hymn:

I’m weary with my former toil,

Here I will sit and rest awhile:

Under the shadow I will be

Of Jesus Christ the apple tree.[3]

In any case, the subject of Eliot’s poetic line is an apple tree with children and the subject of Bruce’s painting is an apple tree with his nine-year-old grandson. Painting, like poetry, is meant to be read. Studying the painted layers of No.1 (Spring) with a bit more attention, we can also engage its weave of ideas: bits of biblical narrative, an iconic modernist poem, a family photograph, and, not least, Herman’s aesthetic. In his new book, Makers by Nature, Bruce offers, “We’re carriers of cultural meanings and values more than we are originators.”[4]

II

With Ben, Bruce cut the fallen apple tree into manageable lengths to be slabbed at a local sawmill. Until the sawyer’s blade reveals it, every mature tree carries a great secret: the character of its interior, its soul. Sawyers often splash a bit of water on freshly cut boards to gain some sense of the wood’s character. Not unlike splitting open a piece of shale to discover the print of a perfectly preserved fern or cracking a geode to behold its crystalline interior, I’ll wager that these common actions are also holy. Mysteries revealed.

Lumber in tow, Bruce returned to his studio in Gloucester, Massachusetts where he stacked the boards and let them cure for 18 months. If No.1 (Spring) bears witness to the apple tree’s earlier life, so also does the newly milled lumber. Last winter Herman had the boards planed and the clean cut of those steel blades further revealed its figured grain. Apple trees often grow in twists and turns torqued as they are in late summer by heavy loads of fruit. Their converging limbs form crotches and joints that over time can generate beautiful burls or reveal distress in curious patches of gray spalting.

Planet earth boasts an estimated three trillion trees. Some percent will be harvested for timber, others clearcut for paper pulp, many more used to stoke fires. But most will remain unnoticed until they join the litter level of the forest floor to decompose. The anonymity of these trees prompts a mind-bending thought; if the universe redounds in beauty, most of its terrestrial and celestial splendors have never been and never will be seen. At least that is the human reality. But if God is the Maker of all things, this beauty has been and is beheld by not just by One, but better—a fellowship of Three.

III

After planing the boards, Herman left them to dry in his studio for another eight months. Then, last summer, he began assembling five finger-jointed boxes from the applewood, one for each grandchild. After sketches, pieces cut to size, joints glued, and finish sanding, at last, the completed boxes were ready to receive several coats of Watco oil, and with it a revelation deeper than the sawyer’s splash. Now we are peering directly into the wood.

In thinking about Herman’s body of work, the applewood’s figured grain is a lovely conceit. The convex and concave lines that wend their way through these boards also appear in the faces, torsos, and limbs of his human subjects. With those souls, the old soul of the apple tree lives on. Ronald Rolheiser observes:

We can imagine aging as a transformation in beauty as much as in biology. The old are like images on display that transpose biological life into imagination and art. The old become strikingly memorable, ancestral representations, characters in the play of civilization, each a unique, irreplaceable figure of value.[5]

Writ large in the figured grain of the old tree is wisdom, the same wisdom that resides in Bruce’s other figurative works in the QU4RTETS series: No.2 (Summer), No.3 (Autumn), and No.4 (Winter).

IV

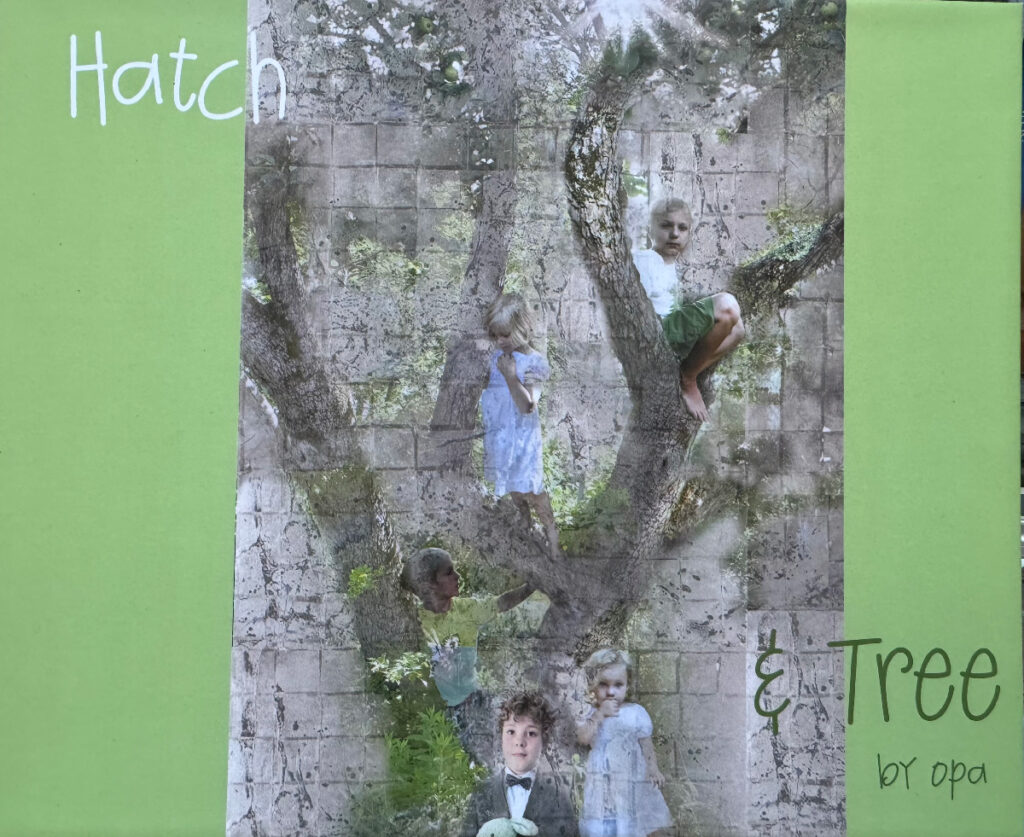

In the final act of this account, the fallen apple tree becomes Tree, a beneficent maternal character. I know this because Bruce allowed me to read Hatch & Tree, a limited-edition book that he wrote and designed as Opa, for his grandchildren.In it he explains:

She was a giving tree and lived to allow singing, laughing children to play in her bough. She was more than a hundred years old and knew a thing or two about the earth and sky. She also knew about people and had seen many people come and grow and leave, and start their own families, bringing their own children to her. And all those children for generations came to play in her branches.[5]

Now we understand Opa’s purpose in handcrafting five wooden containers. They were designed to receive copies of Hatch & Tree and a copy of Eliot’s Four Quartets (for later reading). As the grandchildren opened their Christmas gifts what they would quickly discover is that they are the main characters in this L’Engle-like adventure.

The arc of the story I’ve been telling began with a child playing in an apple tree and ends, as the subtitle of Herman’s storybook suggests, On the occasion of dear Tree’s resurrection. Along the way Will, now twenty-two and about to be married, climbed the tree to survey the world spread before him. An unnamed sawyer revealed the figured grain of the old tree. A painter and maker fit together wooden joints in his shop to fashion treasure boxes. That same maker wove a tale of adventure for his grandchildren—shared memories hidden in cherished new heirlooms.

Ah, the beauty of this sublime world. So many first delights, so much beauty and joy. In due course, all pass from our rich worlds of experience to enter the mysterious domain of memory.

Notes:

“Applewood” is the second in a series of short essays on melancholy.

Special thanks to Laurel G. Anderson’s photograph of the apple orchard.

[1] Eliot’s celebrated Four Quartets is a difficult text. For a well-studied introduction see Thomas Howard, Dove Descending: A Journey into T. S. Eliot’s Four Quartets (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2006).

[2] Wendell Berry, “Poem 2013, VI,” Another Day: Sabbath Poems, 2013-2023 (Berkeley: CA: Counterpoint, 2024), 11.

[3] Richard Hutchings, one verse selected from many variations of the song, The tree of life my soul hath seen (more familiarly, Jesus Christ the Apple Tree), (1761).

[4] Bruce Herman, Makers by Nature: Letters from a Master Painter on Faith, Hope, and Art (Downers Grove, IL: IVP Academic, 2024), 32.

[5] Ronald Rolheiser, Sacred Fire (New York: Image, 2014), 298.

[6] Bruce Herman, Hatch & Tree (Woolwich, ME: 2024).