Watershed

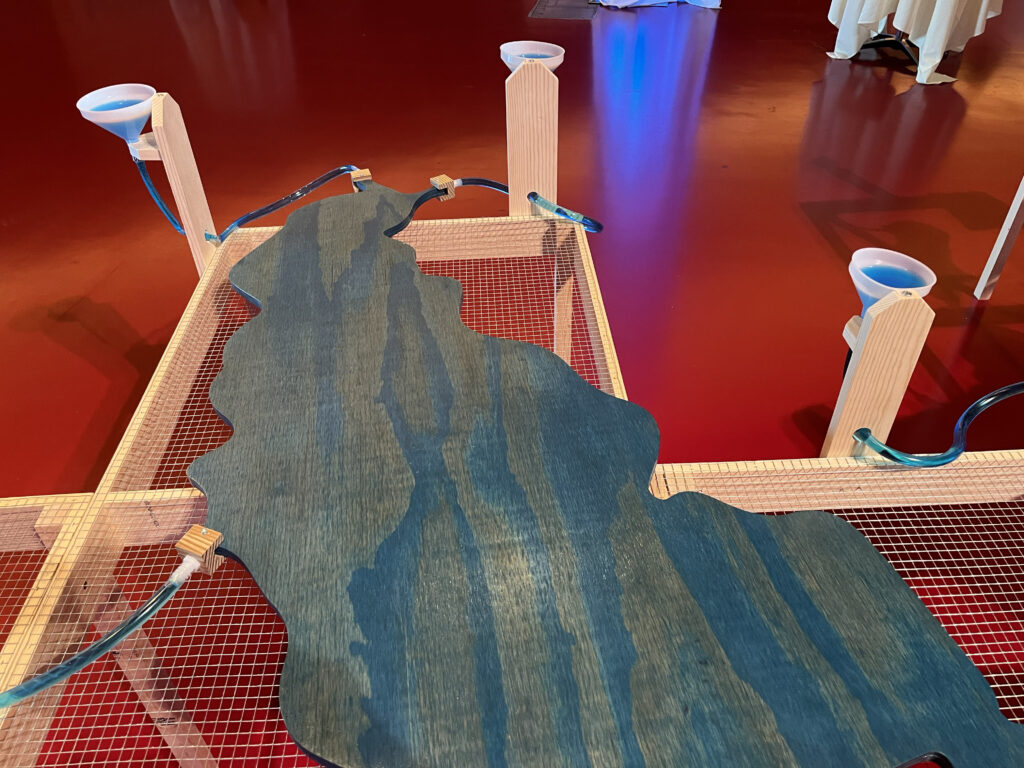

More than any I can recall, Watershed was an entirely serendipitous project. The impetus for it was a spring 2023 conference at Upper House in Madison, Wisconsin. Themed Let the Art Speak: Regarding The Land, colleague Kate Austin and I had hoped to include an art installation in the program, but our best ideas had fallen flat. During a planning meeting Susan Smetzer-Anderson mentioned the Yahara watershed and Melissa Shackelford shared an image of that network with the rest of us. At that moment an idea came to me full force. I imagined creating a piece that would capture the natural spirit of the Yahara watershed, its network of streams, lakes, and wetlands that sustains our city and the surrounding region. Early the next morning and in a quiet moment, I sketched it out.

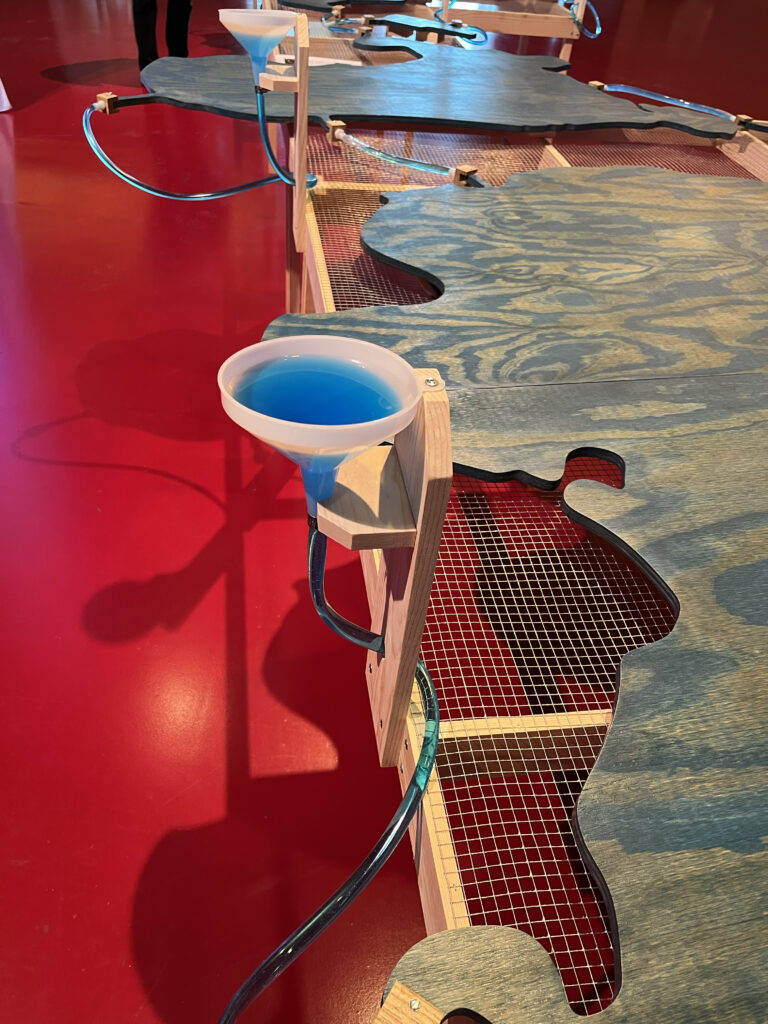

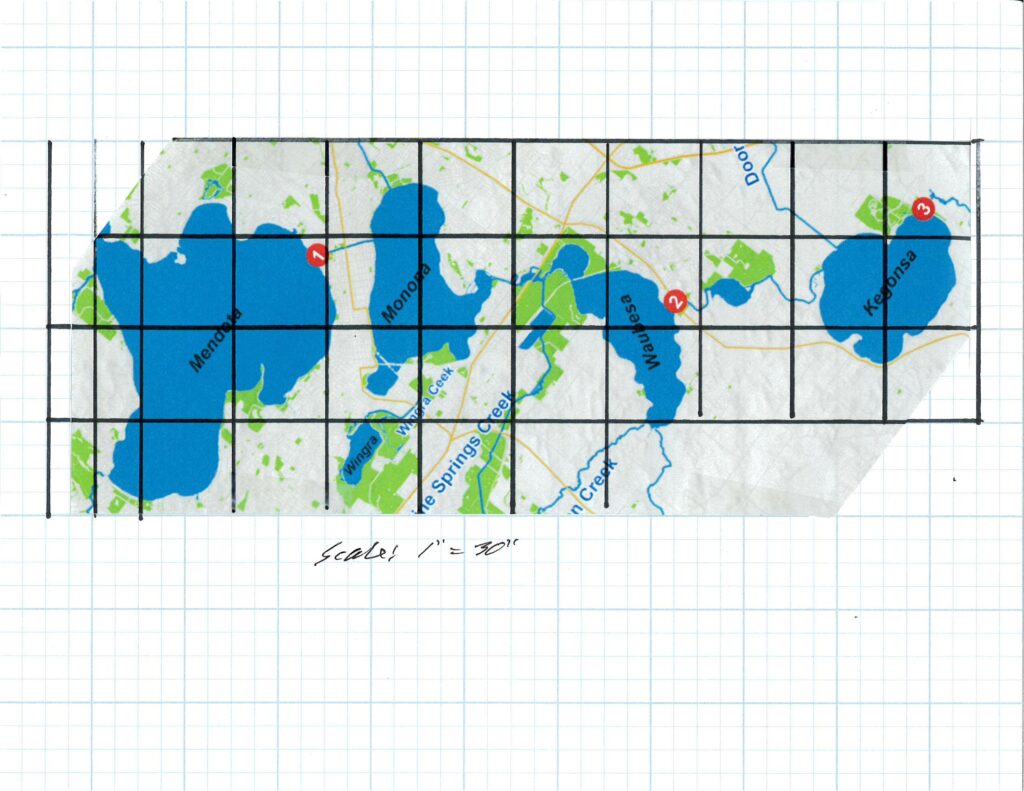

Temporary in nature, I fashioned Watershed from ¾ plywood sheets. Mike Smith’s partnership was essential. He programmed his CNC router to cut the four lakes and smaller bodies of water from the plywood and to scale. I stained the cutouts cobalt blue and finished them with four coats of urethane varnish. To represent the river and streams that feed the lakes, I employed three sizes of white plastic funnels and used clear ½ inch vinyl tubes to make faux connections between the various parts. This interconnected system rested atop tables, legs and frames fashioned of 2 x 2 and 1 x 4 inch pieces of pine and top trimmed out in ½ inch square galvanized fencing material. Finally, I filled the funnels and tubes with water dyed blue. In the end, the entire structure measured 3 feet high, 25 feet wide, and 10 feet deep.

Eighteen days after the conference, Watershed made a second and unanticipated appearance. The annual breakfast meeting of the Madison Clean Lakes Alliance was being held at the Frank Lloyd Wright designed Monona Terrace Conference Center in Madison and nearly 800 guests would attend. Executive Director James Tye invited me to install the piece for their event. As the photos illustrate, the center’s vivid red enamel floors provided a striking contrast for the installation. The following morning Watershed received mention in the Wisconsin State Journal.

In the end, I produced a piece unlike any previous work. The material properties of the piece—it’s hardware-store aesthetic—was still entirely mine, but its temporary, exploratory nature felt entirely fresh. The intriguing structure fashioned from simple materials celebrated the natural environs of the region that has been my home since 1986.

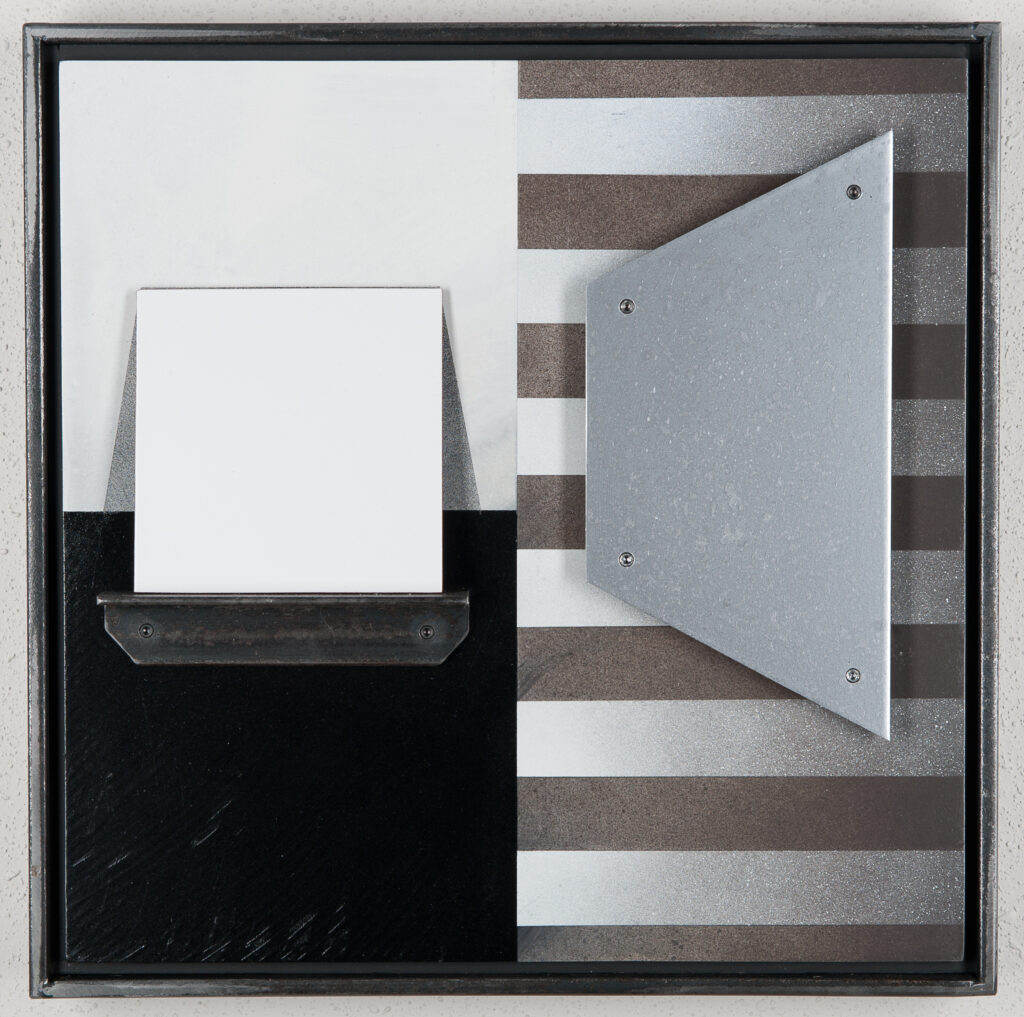

Sentries, Towers, and North Country

For the first ten years of life, I lived with my family on my grandfather’s farm in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. Over the decades I have headed North again and again to vacation, attend family weddings, funerals, and reunions, and seek solace in spiritual retreat.

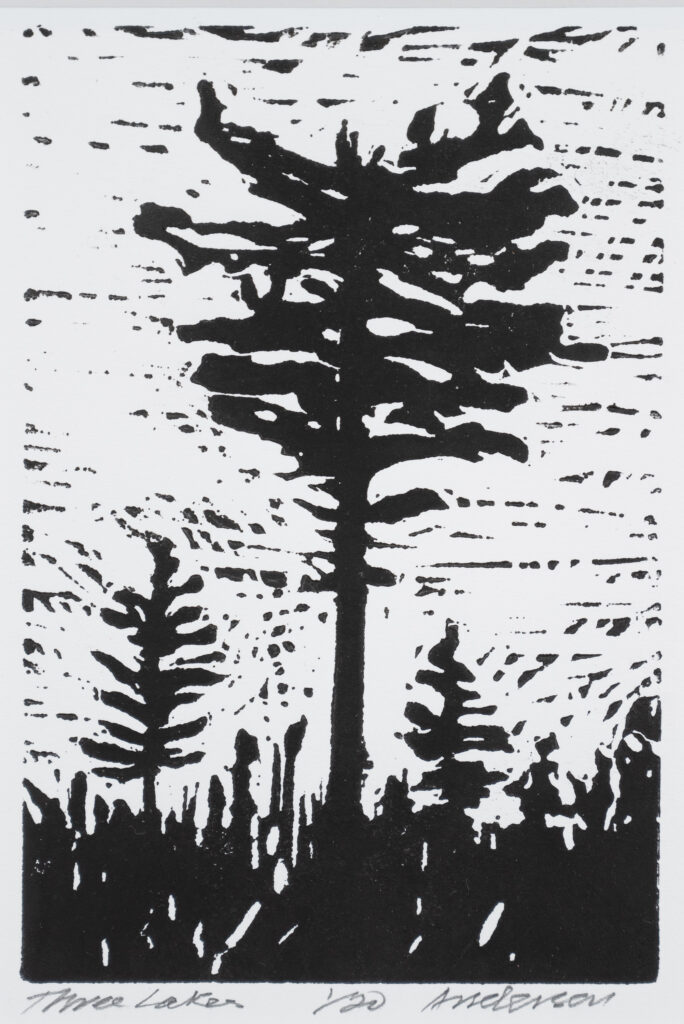

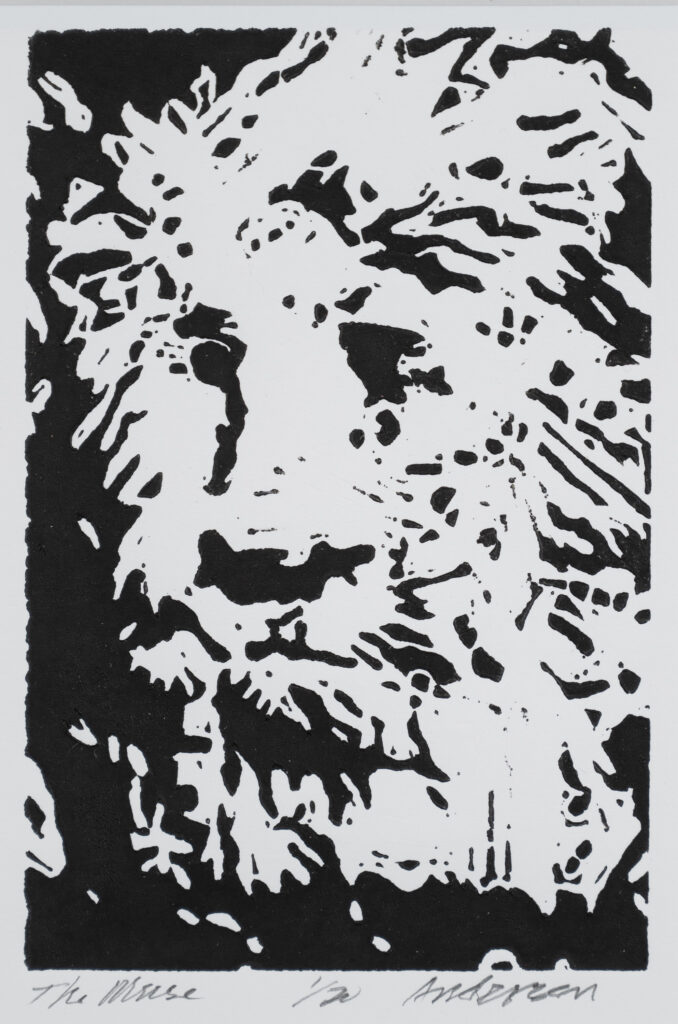

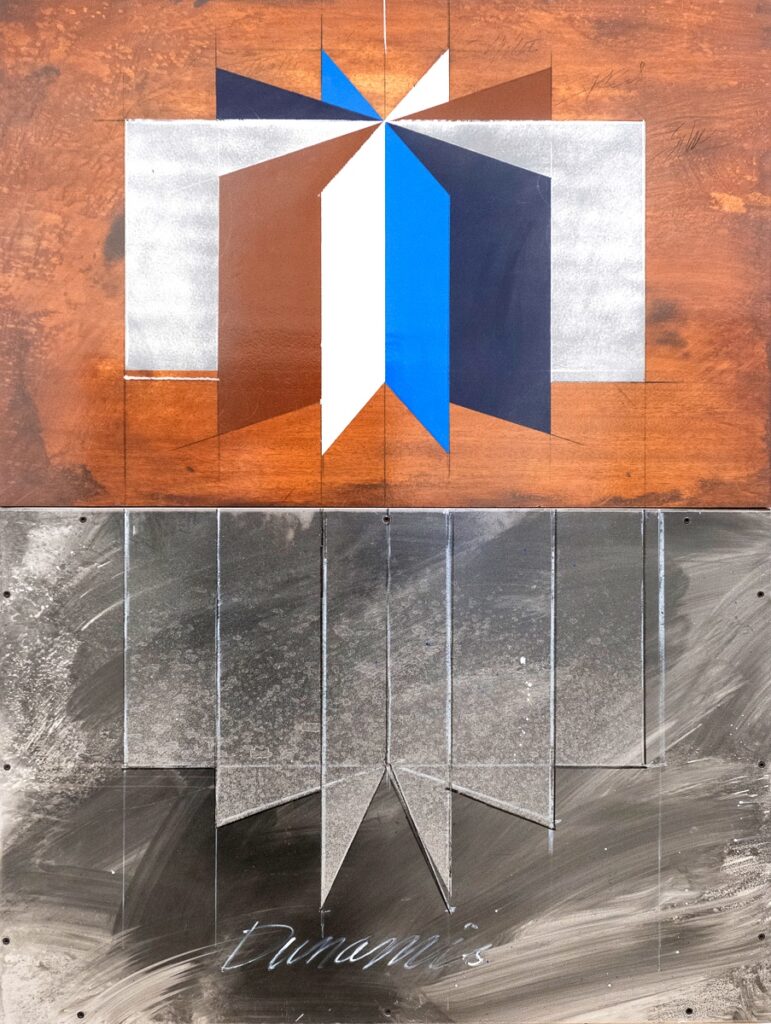

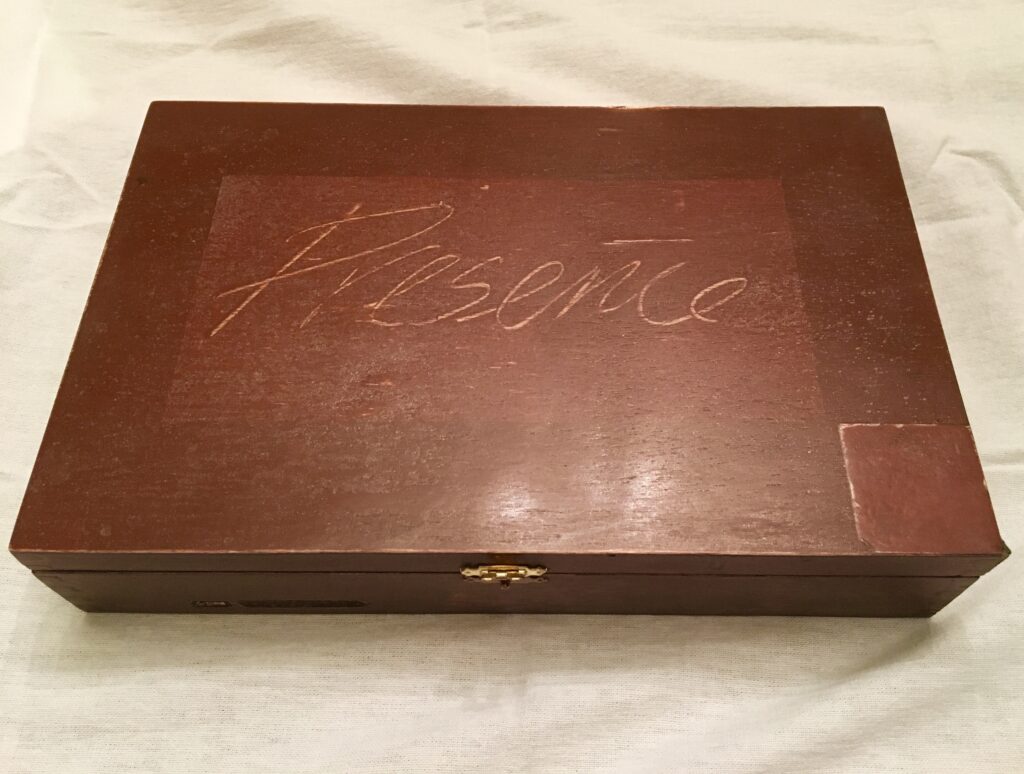

The new assemblages and linocut prints in this exhibit explore my enduring desire to head north. As the various titles suggest, these pieces embody aesthetic dimensions of places fixed in my memory—majestic eastern white pines, collected images and found objects, and old granaries, mills, and lookout towers.

There is a backstory. In his articulation of the Gothic Style, British art critic John Ruskin (1819-1900) considered the rustic timbers, stones, and iron of the North and the artisans who skillfully shaped them foundational. Decades later and in a new forward to his Pilgrim’s Regress, C. S. Lewis (1898-1963) described the spirit or sensation of sehnsucht that had been, since youth, ever-present to him. Here abbreviated, it was: “That unnameable something, desire for which pierces us like a rapier at the smell of bonfire, the sound of wild ducks flying overhead . . . the morning cobwebs in late summer, or the noise of falling waves.”

The character of the north is primal. I was born to it. It lives in me. In recent months, Ruskin’s Gothic sensibility and Lewis’s melancholy have been central to my studio practice. Amid the work of making and writing, a Northern Aesthetic has emerged and work in my studio prompted a season of broad reading, listening, and discernment.

These new works were exhibited in early 2023 at the Overture Center for the Arts in Madison.

Strang, Inc.

When Strang Architecture, Design, and Engineering decided to relocate their Madison office in 2018, Peter Tan invited me to consult with his team about plans for their new reception area. Tan, the firm’s Chief Design Officer, hoped to include work I had been doing with cold rolled steel, especially experiments to develop a patina on the metal. My method included broad brush application of red cider vinegar, powdered graphite, solvents, sanding, grinding, and polyurethane sealer. After much deliberation, we agreed on a concept of three vertically hung 4 x 8 foot sheets of steel and a more narrow horizontal panel of perforated steel spanning the upper half of the assemblage on which the Strang logo would be affixed.

Production became a harrowing process. The sheets of steel I had purchased were nearly impossible to move without another pair of strong hands, and while I could manage the patina process I was developing, in the end I could not control it. As studio work progressed, I began to doubt that I could deliver the final product.

However, once installed the installation took on a warm glow that, as hoped, formed a splendid backdrop for two pairs of Wassily chairs. The chairs, icons of Modern Design, were conceived by Bauhaus-trained artist Marcel Breuer in 1925. The ones belonging to Strang were unusual since the straps fitted to their chrome frames were orange leather, not black leather or canvas, more common applications. Together the oxidized steel panels, handsome Wassily chairs, Strang logo, and finely tuned lighting formed a striking ensemble, like a perfect dinner entrée paired with exceptional wine. For some time I had hoped to install my work in a contemporary architectural space and the Strang project satisfied that desire. I would relish the opportunity to do more.

Approaching the Mystery:

Red, Yellow, Blue

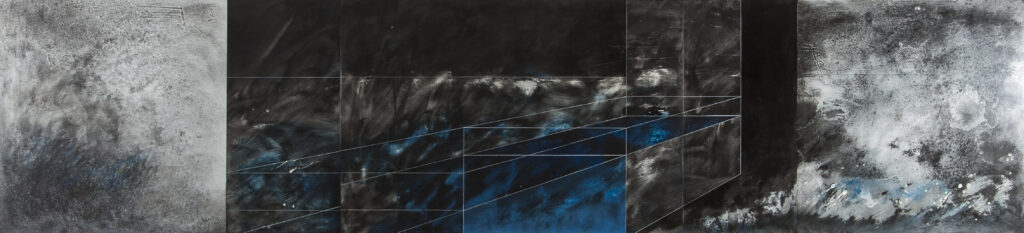

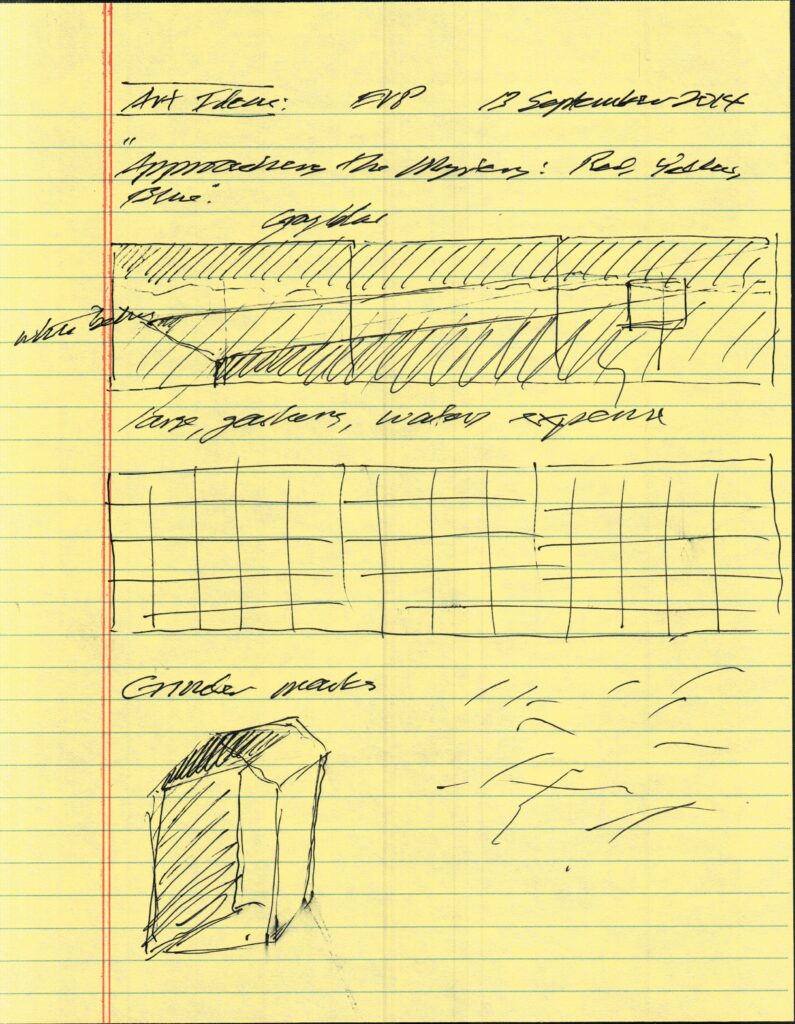

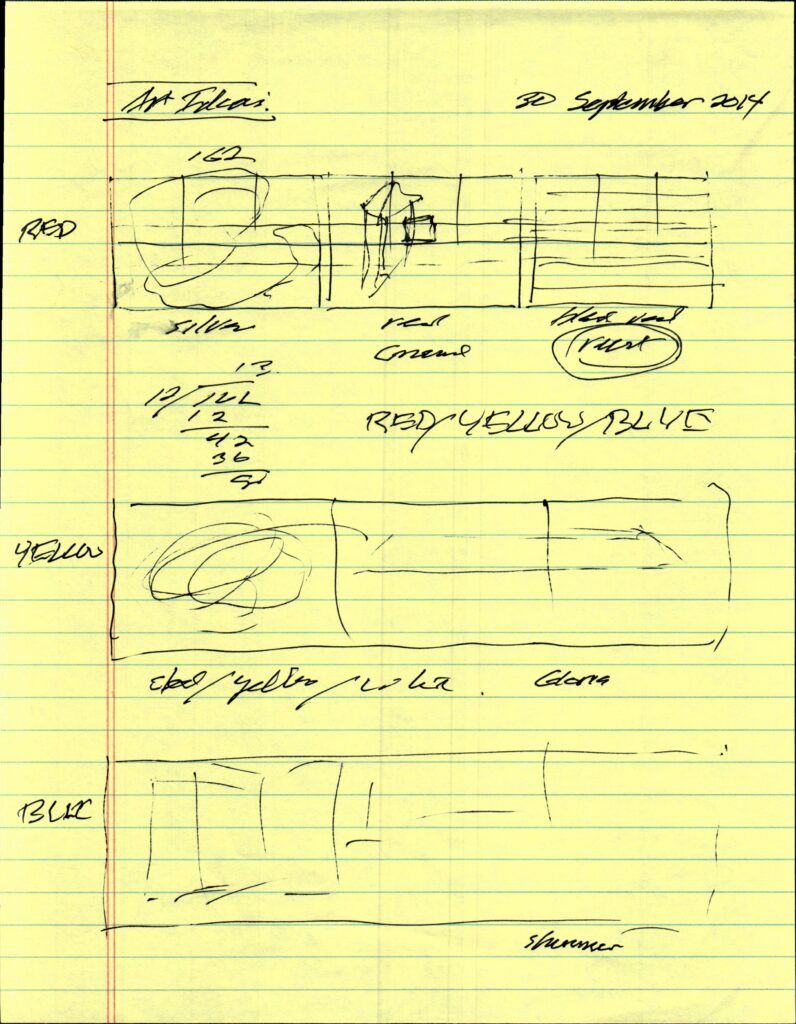

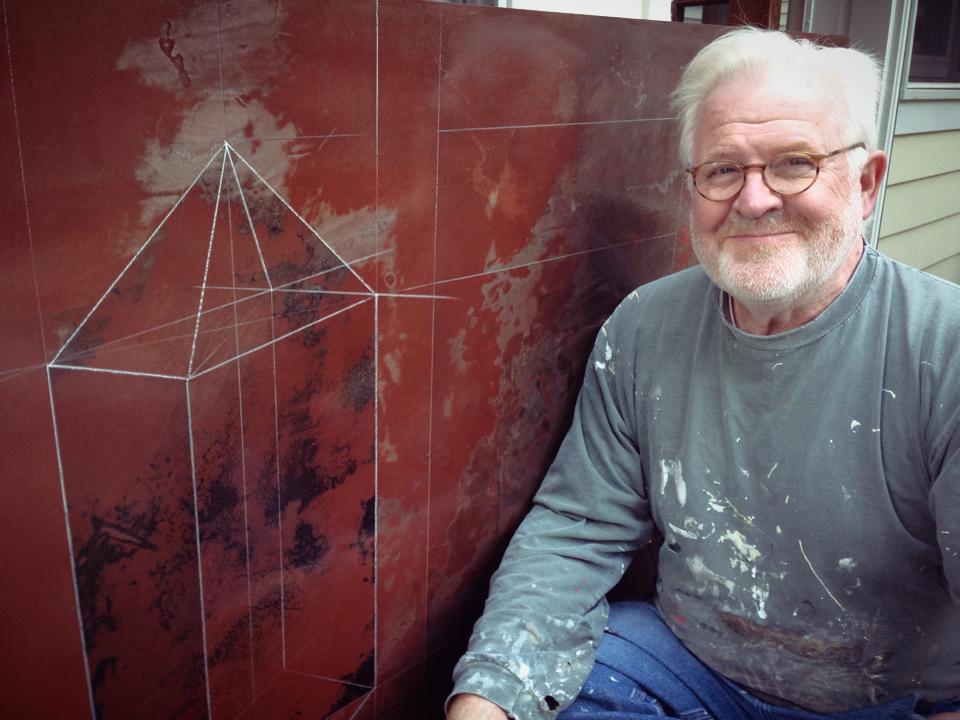

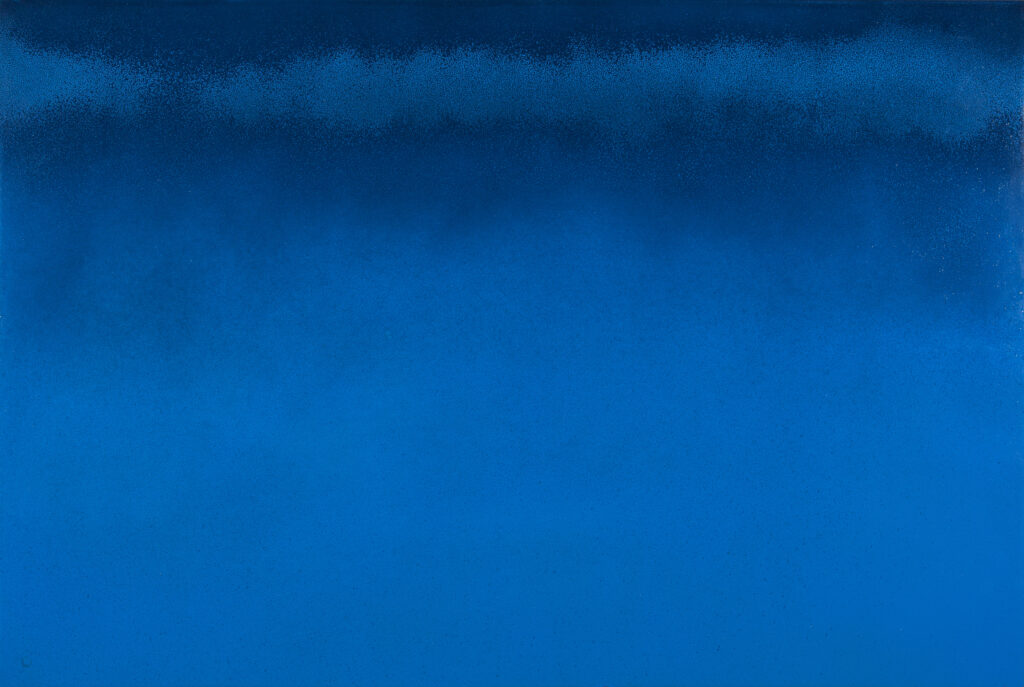

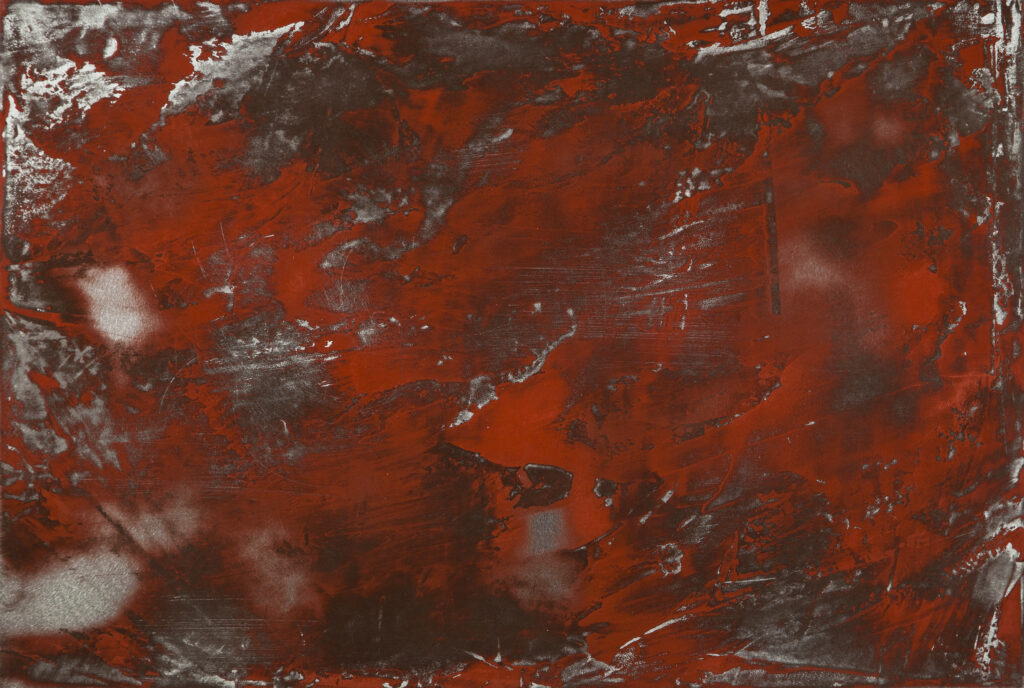

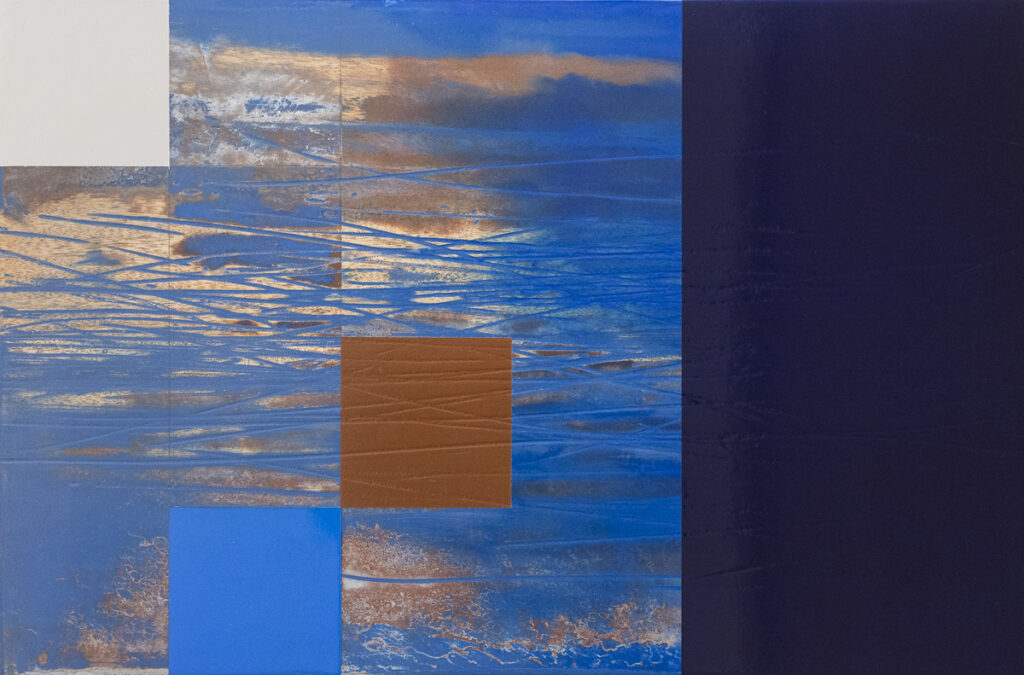

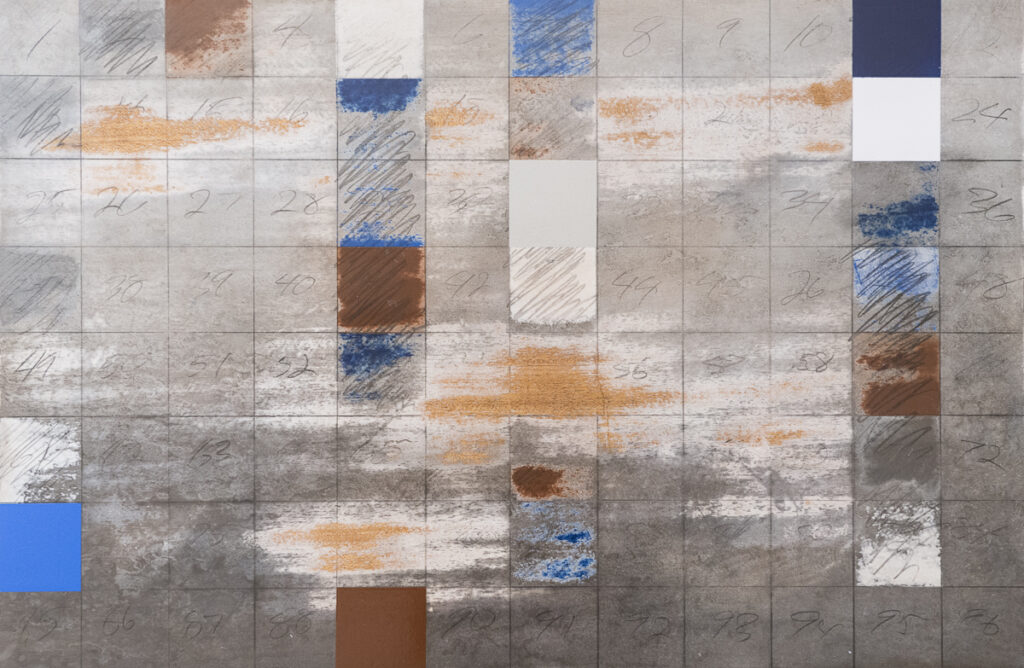

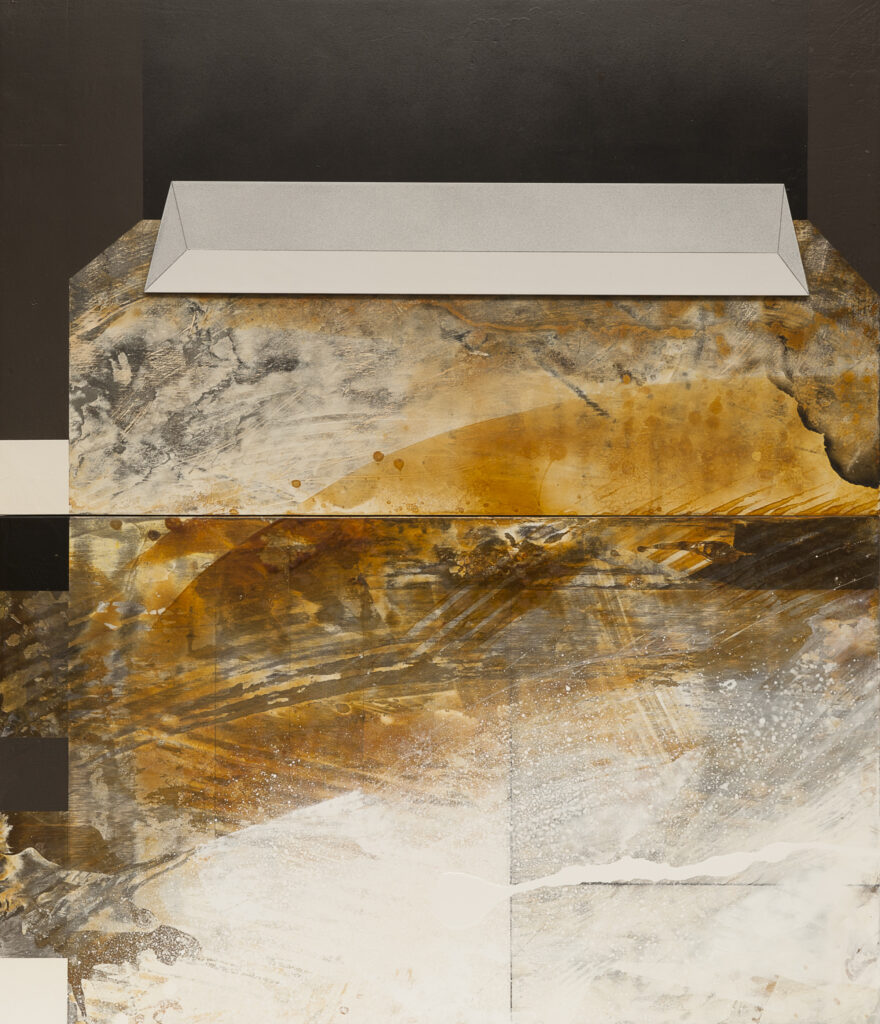

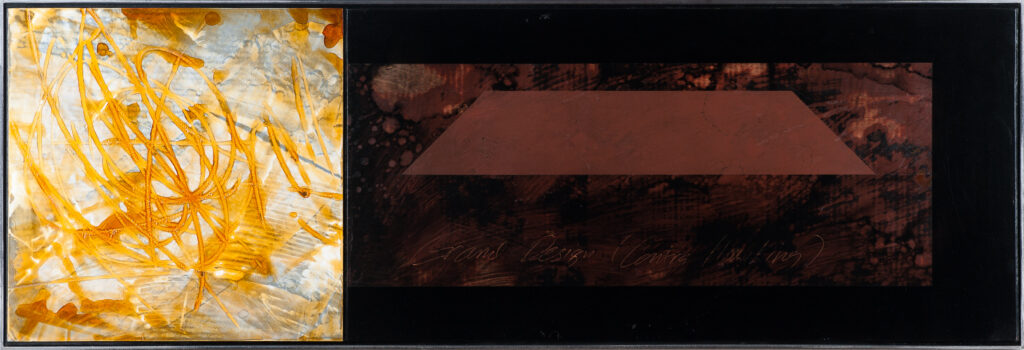

In 2014, an invitation from Judson University to hang a one-person exhibit in their Draewell Gallery breathed first life into an ambitious project. As preparation, I sketched out three landscape-format pieces in my yellow legal pad. I imagined four triptychs (twelve panels in all) painted in enamel on steel and employed a formalist schema—limited palette, materials, and geometric proportions—to guide the project. In its way, these new pieces would be a homage to works like Piet Mondrian’s, Composition with Red, Blue, and Yellow (1930) [image] and Jasper Johns, Painting of Two Balls I (1962) [image]. But my greater ambition was to engage in theological reflection on the nature of the Trinity, the one whom metaphysical poet John Donne described as “three-person’d God.”

Three of the triptychs were very large—3H x 15W feet. Working on this scale with heavy material was an intense experience. More than once while working late and even into morning hours, a wave of despair came over me. Several long journal entries bear witness to the struggle. I needed to let the work become, the paint be paint. I needed to let my initial ideas, material and theological, find their form. The great mystery of God’s being and the possibilities of human making occupying space in the paint-splattered close quarters of my garage studio.

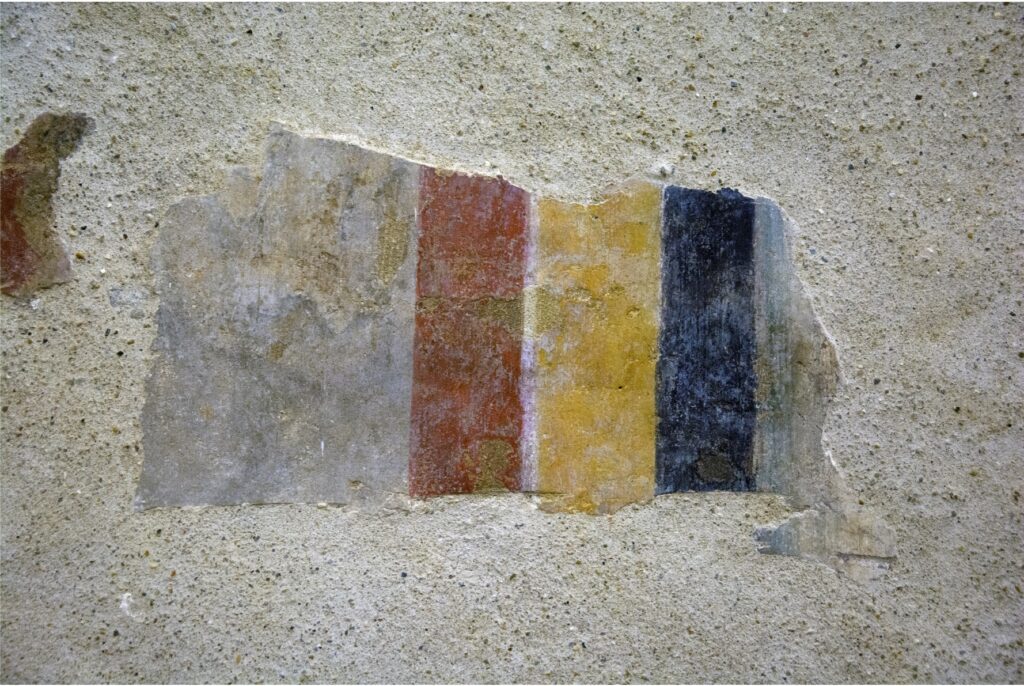

I could not have anticipated what transpired a few months later. In January 2015, I traveled with a dozen friends to Orvieto, Italy. During our last Sunday in the city, host John Skillen invited us to attend mass at San Giovanni Evangelista. This Romanesque church was built in 1004 atop the ruins of an ancient Etruscan temple and located in the city’s medieval district, it is the oldest church in Orvieto. Although the site has been remodeled and renovated several times, some portions of the church’s frescoes remain. That morning on the sanctuary wall immediately to my right a fresco fragment caught my eye. It was the remnant of a picture border rendered in red, yellow, and blue, hues identical to the palette I had chosen for Approaching the Mystery. The visual idea I had been pondering was an old, perhaps ancient idea. For Mondrian and Johns, this palette of primaries was an Avant garde exploration, for the unnamed artist who made this fresco, it was essence.

In years to follow, Approaching the Mystery traveled to several venues. Eventually the Center Gallery at Calvin College purchased the smaller triptych and, sometime later, Door Creek Church purchased two of the large works: Incarnate and Deep Blue.

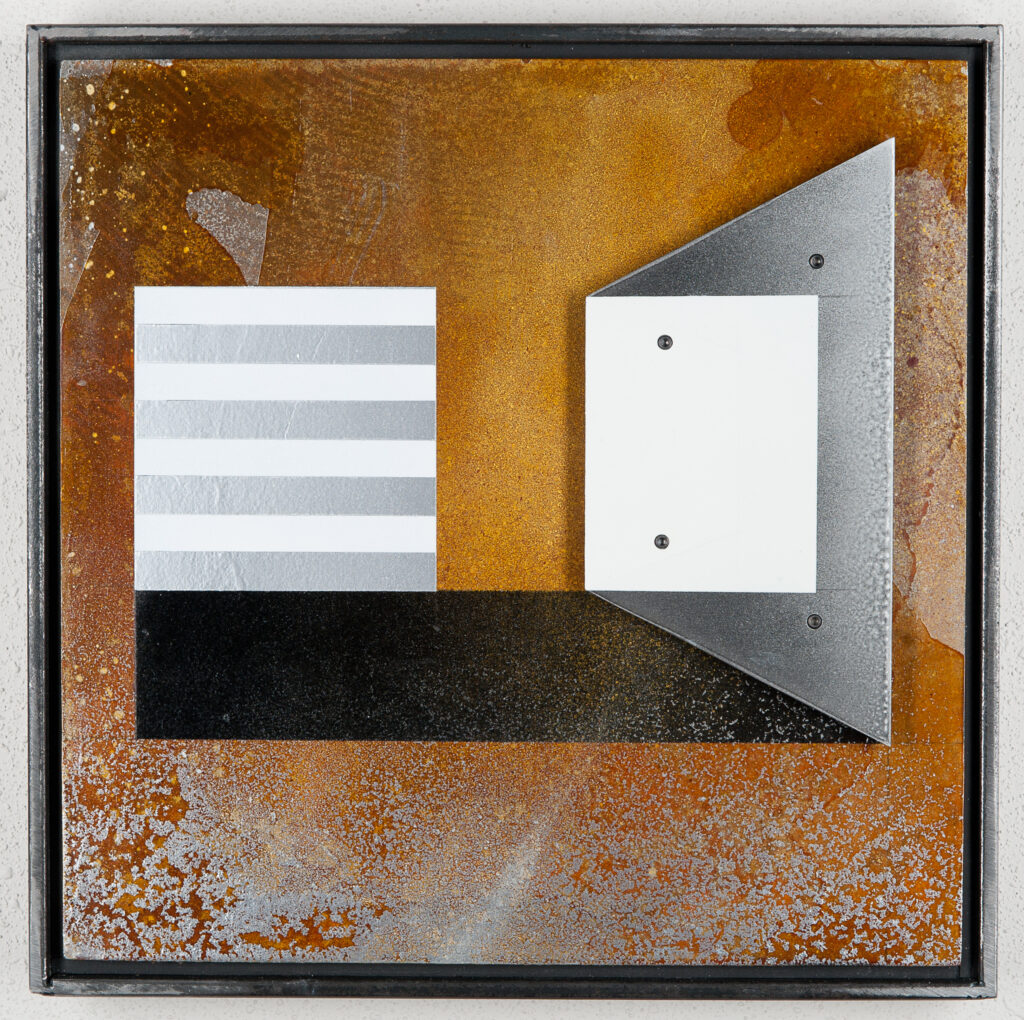

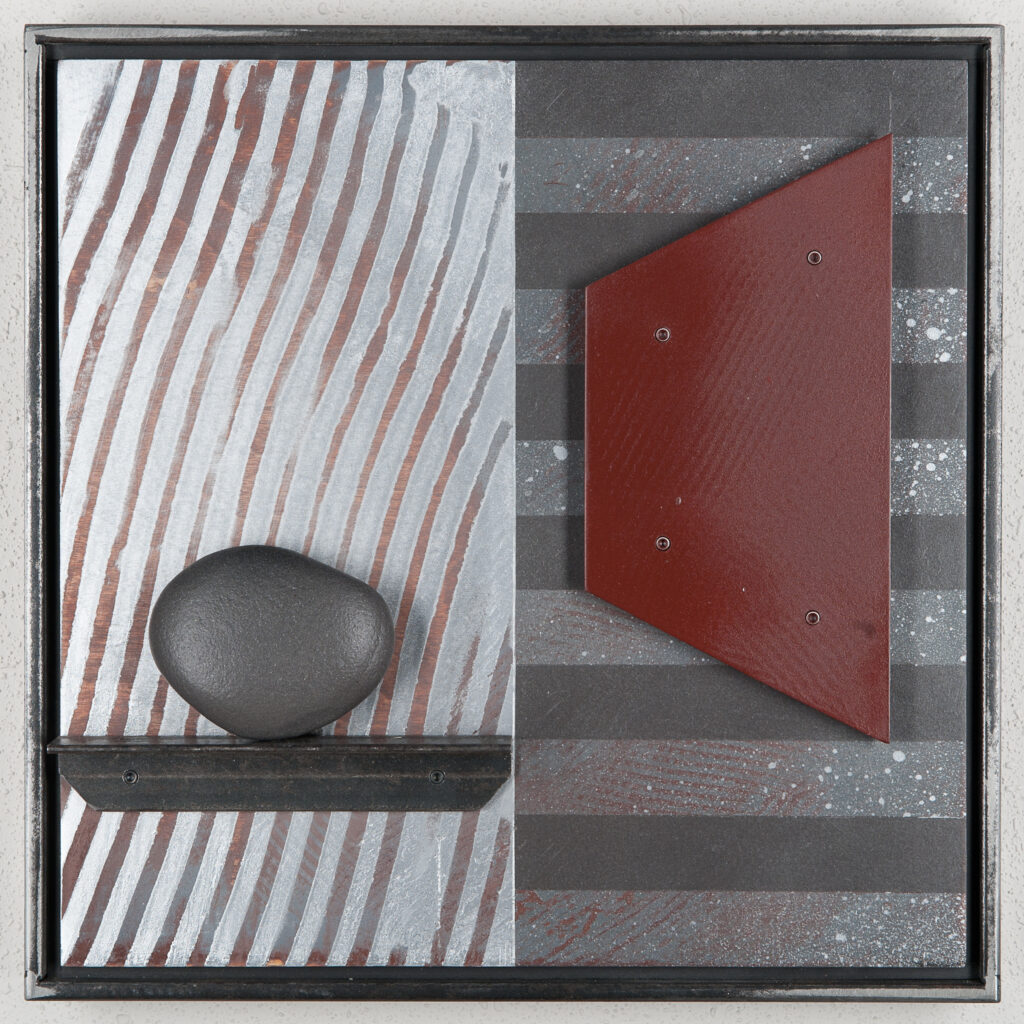

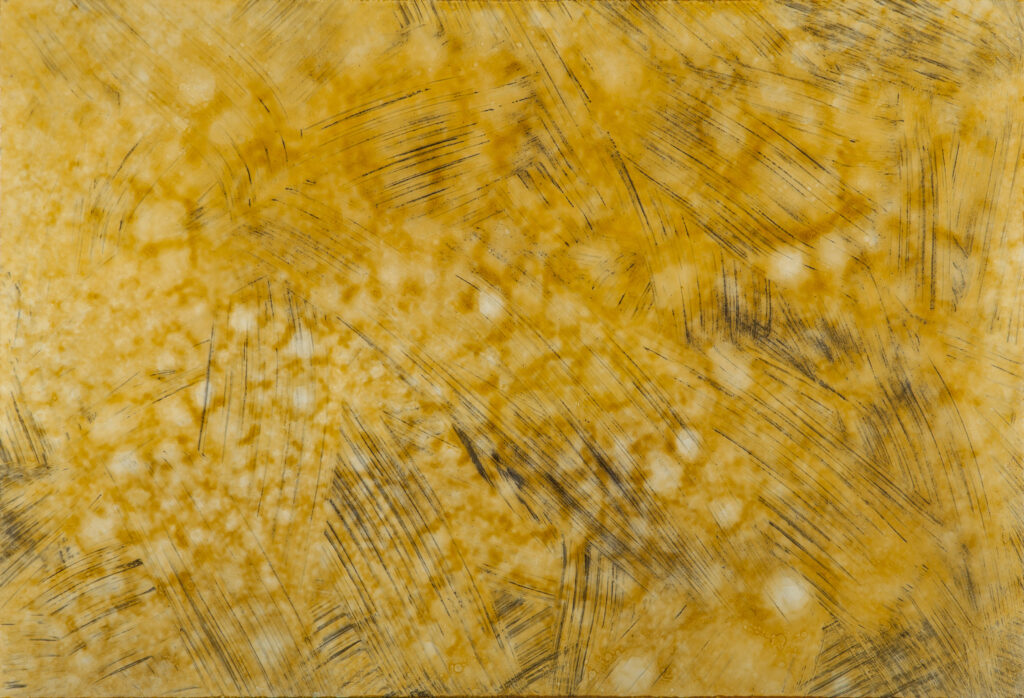

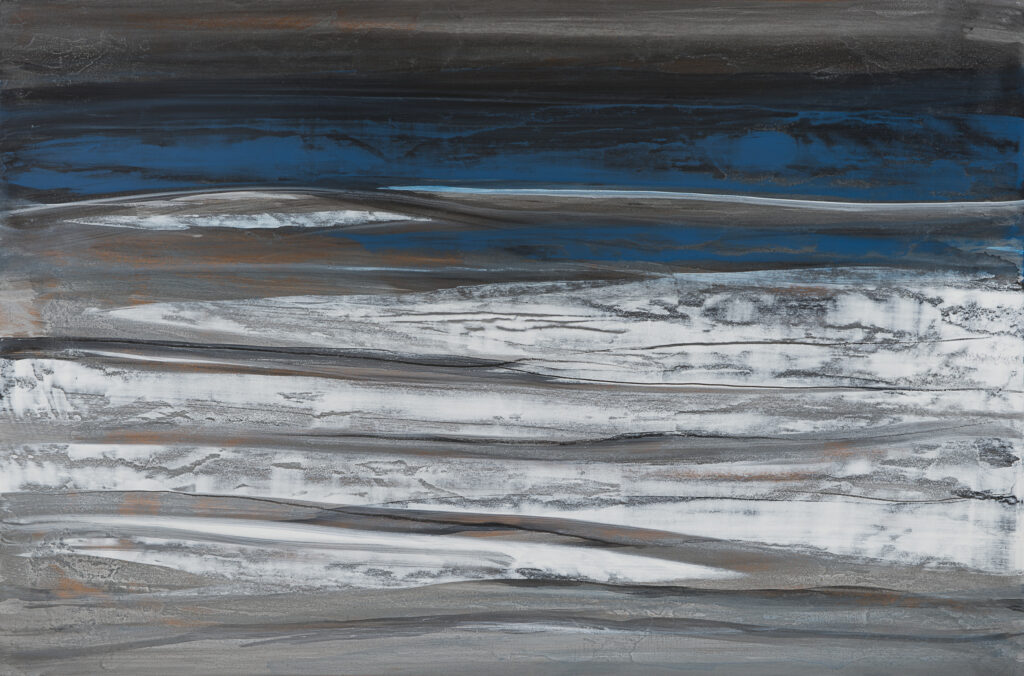

Waiting for the Waters

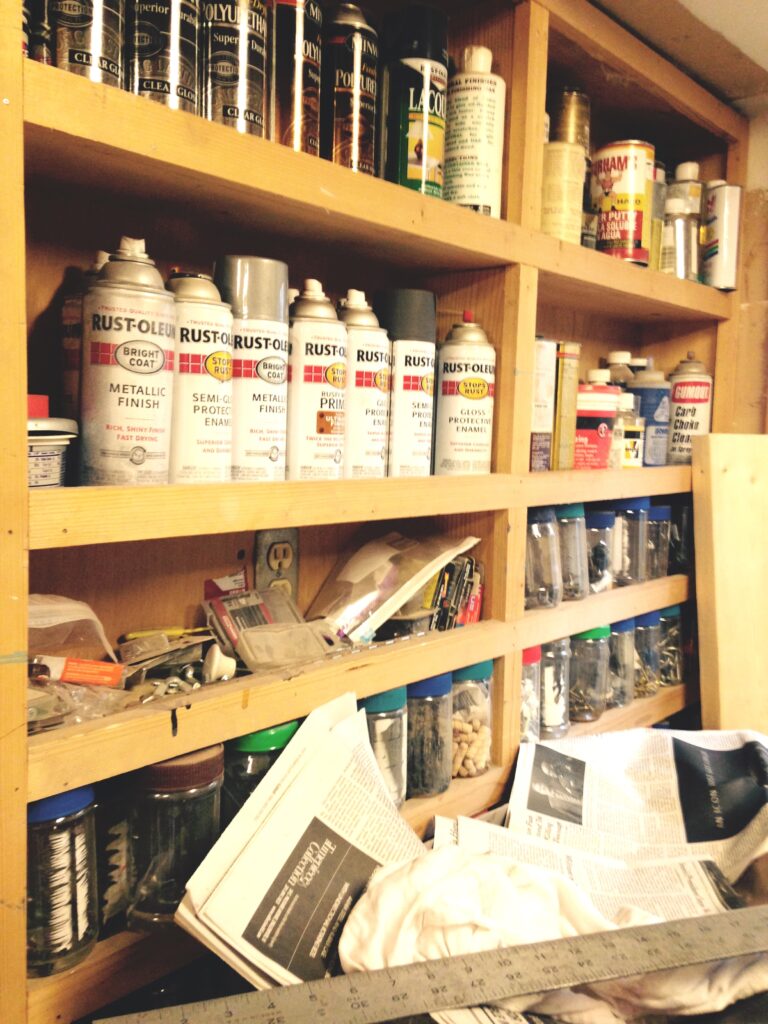

In 2012, Barry Sherbeck and I proposed an exhibit to the Overture Center in Madison, Wisconsin. After several meetings over coffee (sushi too), Waiting for the Waters became our organizing concept. We imagined Barry’s photographs and my paintings as meditations on two biblical texts; the account in John 5 of a man, lame for 38 years, waiting beside the Pool of Beth-zatha for its water to stir so that he could be healed, and Psalm 23, another invitation to wait, though notably beside still waters. Rust-Oleum enamel applied to panels fashioned from mahogany, steel, and galvanized tin were my primary media.

Even as we were creating this work Barry’s wife, Carol, was diagnosed with cancer, and began treatment. Our visual meditations on waiting gained a poignancy we could not have anticipated. Installed on hallway walls opposite each other, the photographs and paintings entered into a rich, albeit unspoken, conversation. We and our viewing friends waited for waters to stir, but we also took in their silence.

Lucent Studio

From 2008 through 2012, friend and photographer Barry Sherbeck hosted a series of exhibits in Madison’s Willy Street Neighborhood. Two rooms in the suite he was leasing had tall ceilings, hardwood floors, and track lights; the makings of a fine gallery. At his invitation, I joined Barry to curate a handful of exhibits in Lucent Studio. We selected themes, invited collaborators, installed work, and hosted receptions. Artists Bobette Rose, Cynthia Reynolds, Eugenia Brown, Gary Nauman, Leslie Iwai, Rachel Durfee, and others joined us to pull together memorable exhibits like Hovering: Waters and Repose, and the company of these friends prompted me to produce exciting new work.

Safe Passage