Having backed tight into our loading dock, the driver hopped from his cab and walked to the rear of the truck where, in one swift motion he grabbed the strap of the cargo door and sent its hinged panels clattering overhead. “I’ve got a shipment for you. It’s heavy.” He slipped his pallet jack beneath the wooden crate, gave it a few pumps, and pulled it inside. “Yeah, could you sign this bill of lading for me? Anyplace is okay. Thanks pal. Have a nice day.”

Denise Weyhrich’s sculpture, Tabernacle, had arrived. It would join thirty-four other works in a traveling exhibit that artist and collector Sandra Bowden and I had co-curated. Come to the Table included everything from an Albrecht Dürer engraving to modernist prints by Jasper Johns and Sadao Watanabe. Most of the contemporary pieces, including Denise’s, had been created by members of CIVA (Christians in the Visual Arts). Come to the Table, a CIVA exhibit, would travel for the next three years to church and university galleries around the country inviting viewers to consider afresh the significance of gathering as God’s people at God’s Table.

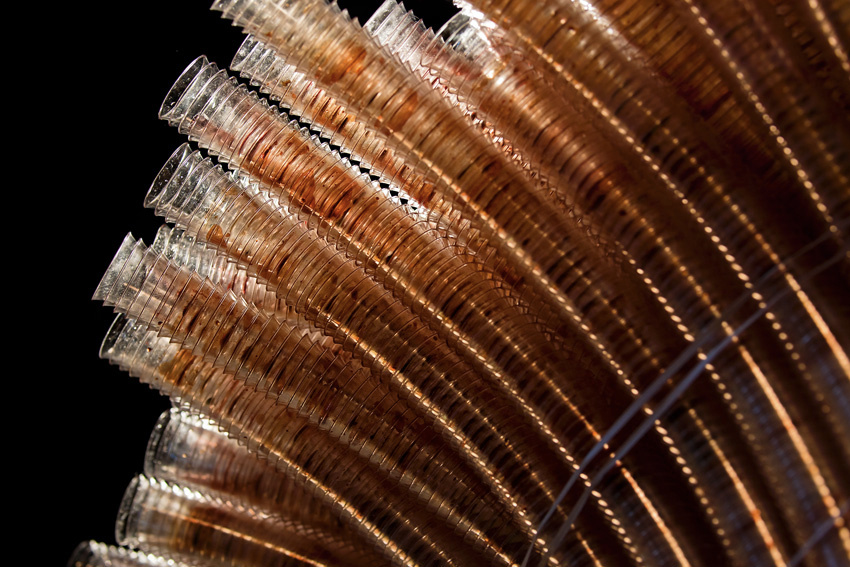

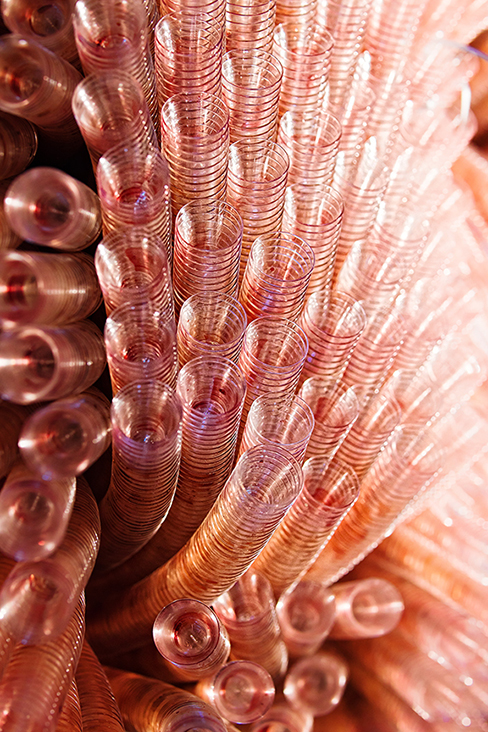

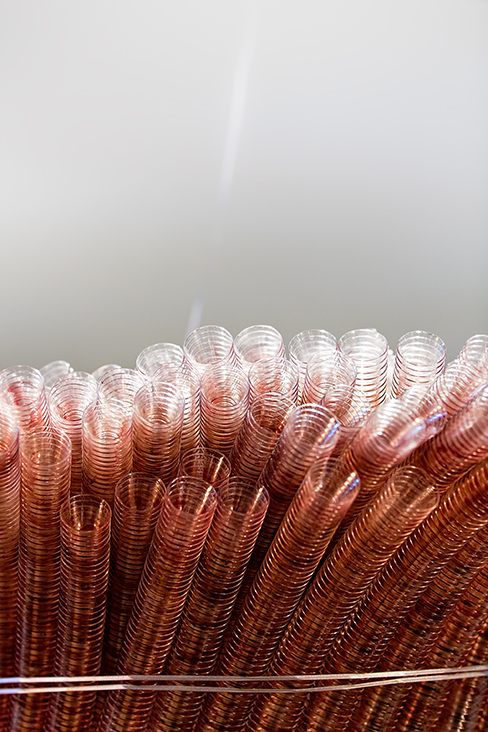

After maneuvering the crate onto a dolly, into the old freight elevator, and through the doors of our gallery, my colleague and I began unpacking the piece. As we peeled away the shroud of plastic wrap that protected Weyhrich’s piece while in transit, a wine-like fragrance filled the room. Tabernacle was fashioned entirely from 70,000 unwashed plastic communion cups. Denise offers, “the people at St John’s Lutheran church did think I was crazy collecting the used cups but they blessed my request just the same.” A year and a half later, Denise completed Tabernacle (2010). As we pulled away the last layer of Saran, a few cups, sometimes in groups of two or three, fell to the floor. The only glue securing the leaning stacks of communion cups together was the sugary residue from the evaporated grape juice. In a moment of slight panic, we did our best to reinsert the cups atop their spindly towers.

Come to the Table premiered at Blackhawk Church in Madison, Wisconsin. A light inside the base of Denise’s ambitious assemblage caused her sculpture to emit a red-amber glow. Tabernacle looked magnificent. But our earlier apprehension about its stability was quickly confirmed. Between worship services, the church atrium where Come to the Table was installed quickly filled with people. Amid hundreds of meetings and greetings and kids rushing about, parishioners barely noticed the sculpture and inadvertently brushed against it. Communion cups fell to the cement floor. Some were quickly retrieved and awkwardly pressed back into place. Others crushed underfoot like empty cicada shells.

In the rural Bible Church where I worshipped as a child, disposable communion cups would have been unthinkable. We were low church Protestants, not Catholics, Episcopalians, or even Lutherans. Even so, my boyish mind reasoned that the glass thimbles from which we sipped a splash of grape juice each month merited careful attention. After Communion the deaconesses washed and dried those little vessels by hand, carefully returning each to their round receptacles in the lidded silver trays from which they’d been served. The trays were covered by a white linen towel and returned to a small closet alongside files of choir music, boxes of candles, and two brass offering plates.

At some point this kind of attentiveness proved impractical for larger contemporary churches. Glass cups were replaced by plastic, silver trays retired in favor of cleverly folded gray cardboard rectangles. On Communion Sundays, soon after the closing benediction, parishioners, making haste to the parking lot, tossed the plastic cups into plastic-lined plastic buckets. Holy remembrance, fleeting. Still, it seems right to suppose that most of the 70,000 cups Denise collected at St. John’s represented at least one moment when a worshipper paused to remember the shed blood of Christ. Welch’s in hand, the suffering and humiliation of Jesus on a Roman cross, the miracle of his resurrection. Not until my early 60’s did I understand that gathering for Holy Communion needed to be the apex of my worship week.

In the upper room the first disciples watched their teacher take a cup and, after giving thanks pass it to them, saying, “Drink from it, all of you; for this is my blood of the covenant, which is poured out for many for the forgiveness of sins.” (Matt 26:27-28) Two millennia later, more than a few theologians are still trying to comprehend the nature of that feast. Real Presence? Holy remembrance? Perhaps Tabernacle, now in the permanent collection of the Sasse Museum of Art, offers some insight. The beauty of Weyhrich’s piece is the manner in which it gathers the quotidian—used plastic communion cups—into a congregation of holy prayers. Seven being the biblical number of completion, Denise used seven silver ribbons to bind the 70,000 cups together. She notes, “The seventh ribbon runs through each stack of cups and to the ceiling, as heavenward prayers of the saints are often illustrated in medieval manuscripts.”

This essay first appeared on April 10, 2025 in the The Lent Project 2025, an online publication of Christianity, Culture & the Arts and Biola University.