By Cameron Anderson

It was my wife, C. K., who christened the first day of December “December Fool’s Day.” December 1st is my birthday, and those who know C. K. will recognize the pronouncement as evidence of her affection and wit. As our family grew, we paused each year between Thanksgiving feasting and the playing of Handel’s Messiah to celebrate December Fool’s Day.

Born in 1953, I turn 70 today. More than my 18th, 21st, or 40th birthdays this one seems consequential. The new decade it signals is not unlike a curious object one holds up to study in the light. In this instance, two realities prompt scrutiny: the advance of my wife’s early onset Alzheimer’s and my inner fire to make and write.

C. K. will not remember that today is December Fool’s Day. Dementia steals these details from her. In earlier times this good woman clipped articles from the Sunday New York Times she knew I would want to read. She expertly copyedited my manuscript for The Faithful Artist, published by IVP Academic in 2016. Seated at our dining room table with red pen in hand, she announced: “You really don’t understand commas, do you? . . . and semicolons, don’t get me started!” Affection and wit.

These days the memory of longtime loves—family members, our little house on Rust Street, keepsakes—slips away. She revisits simple stories and photos again and again; attempts, it seems, to forestall their complete erasure. And so the covenant that C. K. and I made before God and friends on August 23, 1975, schools us. Tragically, her disease also keeps covenant.

Caregiving and creative work are disgruntled companions, each steals precious attention from the other. I do not entertain romantic notions about how this will go: that my wife’s decline will make me a better artist or that creative work will make me a better caregiver. What I can say is that both are my work, work assigned to me before time, work that is mine to do now.

On the creative front my projects are heading in good directions. The publication of a book in 2021, the relocation of my studio in 2022, and two new exhibits earlier this year have been helpful signposts to get me to the point I am now.

In 2021 IVP Academic published God in the Modern Wing: Viewing Art With Eyes of Faith, a book I co-edited with biblical scholar G. Walter Hansen. Preparing essays for a multi-contributor volume and gaining art-image copyright permissions requires more than a little rigor. But somehow opening a carton of freshly printed books ignites one’s desire to do more. Future writing plans include monthly posts for this website; the completion of a long-form essay entitled Sentries, Towers, and North Country, stimulated by my Overture exhibit earlier this year; and, long in the works, a more substantial book entitled The Garden: An Artist Reads Genesis 1-3.

A troubling season followed. The center of the consternation was the close of a generous studio I had been leasing on Madison’s east side. I remodeled the space with the help of friends and early on it was a joyful and generative place. But for reasons unspoken here, those satisfactions had been carried off. Matters came to a head in 2020 when a developer purchased—849 East Washington Avenue—and all but its façade was scheduled for demolition. In January 2022, just as my lease ended, a deep winter freeze triggered the sprinkler system and the studio flooded with several inches of water. Tools now rusted, wooden crates full of art soaked, books ruined, final retreat was urgent. Months later, my loading dock studio as well as the CIVA office and gallery (located in the same building, and which I had also leased and remodeled) were reduced to rubble. It was a cathartic reckoning.

The Wisdom writer acknowledges life’s ebb and flow. There is “a time to tear down,” but also “a time to build.” In due course I began to experience sweet release from lost labors and relationships. I gutted my home workshop and installed new insulation, power circuits, lights, and even heat. I purchased an enormous tool chest. I cleaned and sharpened my tools. I sorted bins and boxes of screws, brads, and assorted hardware. I built a workbench from recycled red oak. My modest makerspace in order, I tuned-up a second clean space in our basement.

Tearing down and building up became prelude. Early in 2023 a wild season of artmaking commenced. First was preparation for Sentries, Towers, and North Country, installed on March 10 at the Overture Center in Madison, Wisconsin. Colleague Susan Smetzer-Anderson posted a thoughtful blog about this new body of work. On the heels of the Overture exhibit came the manic making of Watershed, a temporary installation I constructed for the second-annual Let The Art Speak conference held at Upper House on April 15. Friends Barry Sherbeck, Bill Montei, Kate Austin, Mike Smith, and Scott Wilson contributed to its success. During the conference, friend Galen Hasler texted an image of the installation to James Tye, Executive Director of the Clean Lakes Alliance. Eighteen days later Watershed was on view at the organization’s annual 800-person breakfast held in the ground floor Madison’s Monona Terrace. The following morning it received mention in the Wisconsin State Journal. I was out of breath. But that whirlwind of making was deeply satisfying.

Our lives follow a path and we invoke terms like fate, karma, providence, or calling to sort that fact. In some measure we get to chart a course. But we are not, as the Stoics believed, “masters of our fate.” Every human plan is contingent. That fact leads me to wonder what the next decade may hold.

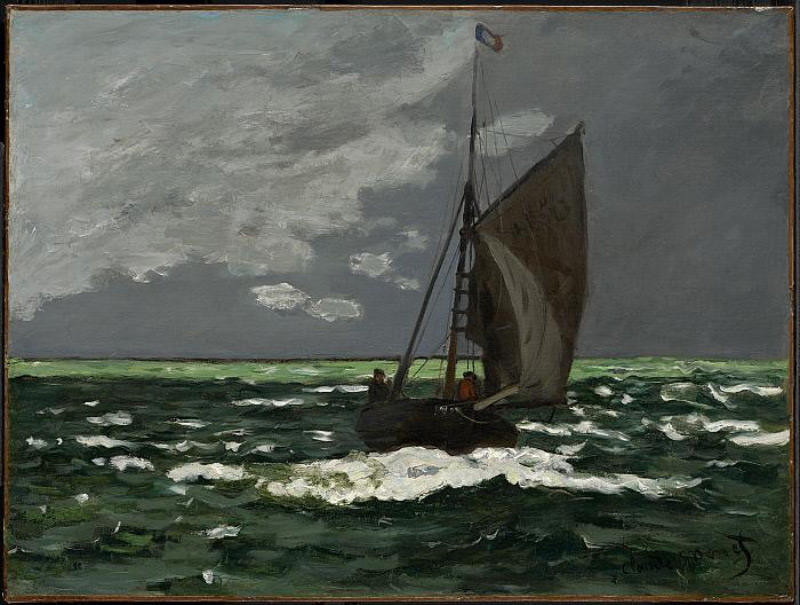

For many years Pat Jones and John McCray welcomed me to their beautiful country house in the Berkshires where, late in summer, I enjoyed their extraordinary hospitality. It was on a daytrip with Pat and John to the Clark Art Institute in Williamstown, Massachusetts I first saw Claude Monet’s Seascape, Storm (1866). To my aesthetic mind, this small painting is a nearly perfect work.

Seascape, Storm, a painting by Claude Monet

The upper half of Seascape, Storm features a slate sky resting heavy on the green-black sea beneath. From the left edge of the picture plane, thickly scumbled light gray clouds blow right toward the mast of a boat. Wind fills its sail and a row of roiling whitecaps undergirds the silhouetted vessel as it navigates choppy waters. The efficiency of Monet’s brush is impressive. This dramatic scene depicts a classic trope: persons vs. nature. But, a painter myself, I dare to believe that Monet’s true purpose in making this painting was to capture the scene’s emerald-green horizon—rendered less as a line of demarcation where earth and heaven meet and more a place or realm just beyond.

Horizons are powerful metaphors. They represent the future as a possible goal or destination. For most of life I encountered these realities as faraway abstractions. My sense was that I would live for a long while. I reasoned that, though there were many things I hoped to accomplish, there would be many seasons in which to do them. Friendships would wax and wane. Instances of mastery would be countered by error. I would journey forth but always head home. There would be time. No longer.

Astrophysicists now believe that the universe (or multiverse) is expanding at a stunning pace. By contrast our earthly futures have an end point. But I lift Monet’s jewel of a painting to the light, so to speak, and am stirred again to encounter art as metaphor. In it there is a horizon just ahead, but beyond it another filled with emerald-green light. That second space holds back the leaden sky pressing down and my spirit heads toward it.