I

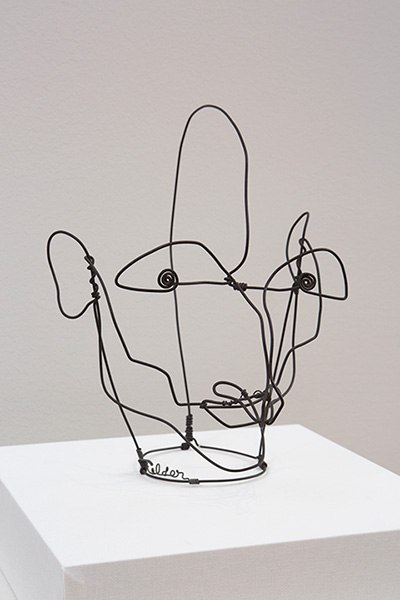

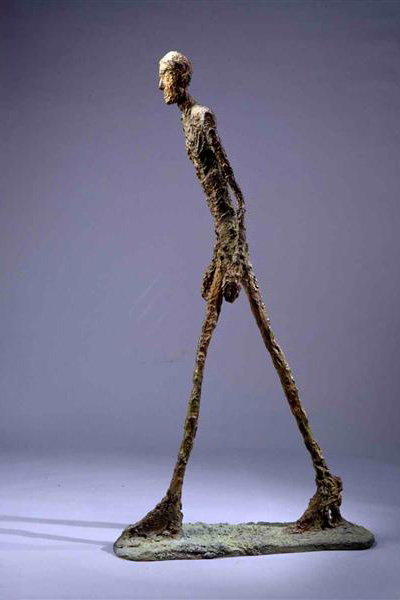

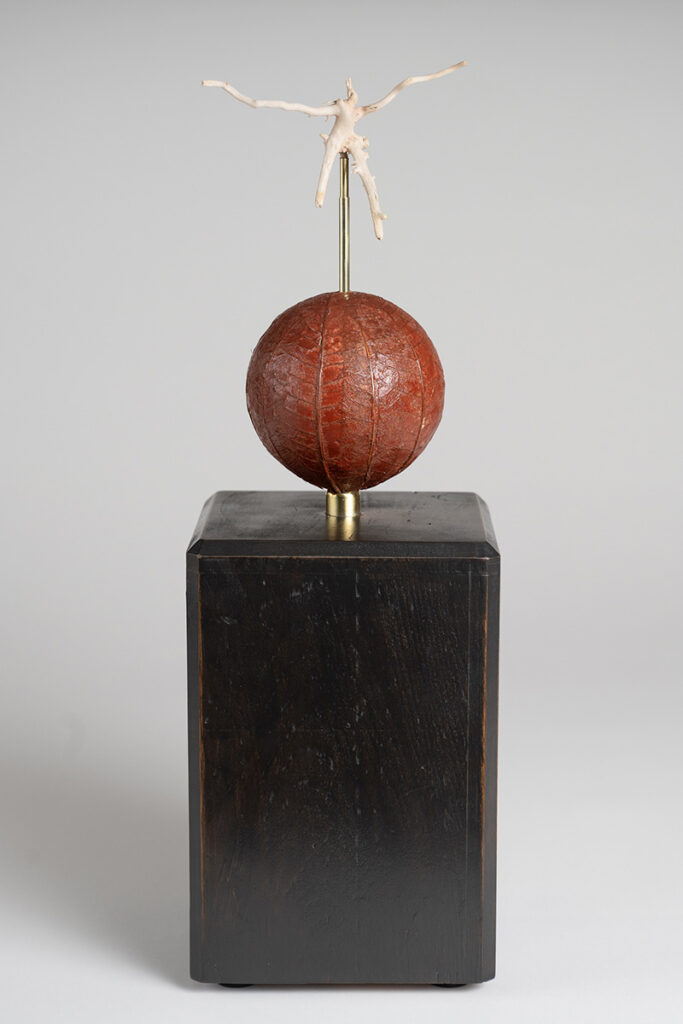

Some time ago, while combing a Lake Huron shoreline, I spotted a bleached root that registered immediately as a small human figure. Its form reminded me of modern works like Alberto Giacometti’s elongated bronze sculptures and Alexander Calder’s playful wire drawings. I kept the found object nearby, sensing I might make something of it. In recent months, Roi, pictured above, emerged.[1]

Alexander Calder, Portrait of De Celeyran (Michel Tapié), (c. 1930)

Alberto Giacometti, Walking Man I (1960)

At first the frail man seemed to be running wildly away, as from a house afire. But the essence of a project often evolves in its making. When I mounted the stick figure atop the red oxide sphere—another found object, polychromed with red primer and clear lacquer—I sensed Roi, French for king, rushing forward like the Son of Man loosed from his tomb.

Cameron Anderson, Roi

mixed media assemblage (2025)

I finished Roi’s pedestal, a cedar beam cutoff, with a mixture of powdered graphite and urethane, and used several diameters of brass tubing to connect the parts. Here I saw the Spirit of Christ striding Creation, jetsam prompting theological reflection. My fanciful imagining was not without precedent.

In her novella The Spirit Level, Chloe Aridjis recounts the story of Christ the Vine:

According to legend a Jewish laborer was working in his vineyard when he came across this particular figure with reddish roots sprouting from his head, beard, ears, groin and armpits. The man interpreted it as a sign and converted to Christianity, then donated it to the archbishop of Toledo, who would later carry the image with him to Valladoid, where it became an icon in the seventeenth century, held aloft during festival processions, people praying to the tiny Christ as they begged for rain.[2]

Christ the Vine (c. 1400), Prado Museum

I am not attracted to the crude root, but the story of a farmer unearthing a likeness of Jesus is a delight. For several hundred years his discovery was considered a sacred relic until, as Aridjis explains, “The powers of the man-root were deactivated in the eighteenth century when the Age of Enlightenment removed its charge, and the rain was seen to fall regardless.”[3]

The writer’s account is instructive. Through the ages theologians have quarreled, sometimes viciously, about the legitimacy of fashioning likenesses of Jesus. Are such things idols or icons? If permitted, how might an artist render the Galilean for whom no extant images exist? For that matter, how could anyone hope to depict the one whom the apostles believed was the very fullness of God? It’s a long contest of convictions that begins with third-century images of Jesus the Good Shepherd and travels the centuries to include everything from icon writers applying egg tempera and gold leaf on gessoed panels to outsider artists brushing household enamel onto wooden cutouts, and from Catholic orders and modernist painters producing Stations of the Cross to Andy Warhol’s extensive appropriation of da Vinci’s Last Supper.

The scope and range of these Jesus images is encyclopedic, and the controversy, evergreen. Catholic and Protestant gift stores are filled with plastic figures, prayer cards, and T-shirts bearing images of Jesus. To some this is religious kitsch, “Jesus Junk.” To others, cherished objects of devotion.[4] There is a wide meaning-gap between mass-produced devotional objects and religious paintings and sculptures the artworld deems significant. Absent any easy resolution between low- and high-culture taste, let each thing be what it is in the eyes of its beholder.

Albrecht Dürer, Ecce Homo, detail (1512)

Mark Wallinger, Ecce Homo, detail (1999)

II

Back to Roi. It’s the earthier depictions of Jesus that draw me in. In John’s Gospel for instance, Jesus, defending the woman caught in adultery, “bent down and wrote with his finger in the ground.” (8:6) On seeing a man blind from birth, Jesus “spat on the ground and made mud with the saliva and spread the mud on the man’s eyes, saying to him, ‘Go, wash in the pool of Siloam.’ Then he went and washed and came back able to see.” (9:6-7) When he learned from Mary that his dear friend Lazarus, her brother, had died, Jesus “began to weep.” (11:35)

As John’s account moves toward Jerusalem, Pontus Pilate, Roman Governor of Judea, arrests Jesus and has him flogged. Roman soldiers curse and beat him. And at the conclusion of Pilate’s interrogation the governor presents Jesus to the angry mob wearing a crown of thorns and purple robe. “Behold the man! (ecce homo),” declares Pilate (19:5). How shall we understand his meaning? Did Pilate speak these words as mockery? Had he unwittingly foretold Jesus’ coming rule and reign? Jesus is crucified.

A week or so after his resurrection, seven of Jesus’ disciples returned to Galilee and set out on the lake to catch some fish. They labored in vain until, near dawn, their master appeared and granted them a miraculous catch. Boats now laden with fish (153!), they returned to shore to find “a charcoal fire, with fish on it, and bread . . . Jesus said to them, ‘Come have breakfast.’ Jesus came and took the bread and gave it to them and did the same with the fish.” (21:9-13).

True religion is not ethereal, but grounded, not wafting in the sweet by and by, but corporeally present. If, in his humanity, the Son of Man was what we are, might we also say that the incarnation is the central pole that supports the tent of all human being and meaning?

Imagining the man fashioned from driftwood charging like a king into the world, prompted me to revisit Gerard Manley Hopkins’ poem “The Kingfisher Catches Fire.” As the poet’s “just man” enacts grace in all things, he:

Acts in God’s eye what in God’s eye he is—

Chríst—for Christ plays in ten thousand places,

Lovely in limbs, and lovely in eyes not his

To the Father through the features of men’s faces.[6]

Though not easily sorted, one might read Hopkins’ closing lines like this: lovely in limbs and eyes and each a unique human visage, we, now Christ ourselves, play like a troop of actors in ten thousand places on Creation’s stage.

III

Human encounters in the world sustain my life and, again and again, help me locate my reason for being. This is how each generation works out what Madeleine L’Engle once described as the “tragedy and glory” of being human. But these days I often encounter the pace, scale, and dislocation of late-modern life as a threat. The algorithms of social media have caused disasters, deals, and discounts to become daily bread. Moment by moment the dopamine-drip of digital devices corrodes my “inscape,” (Hopkins’ term). And just as every Amazon shipment is tracked, so also am I. The whole world—its pleasures and maladies—beckons and my finite being is overwhelmed.

In 1917 Russian theorist and critic Viktor Shklovsky wrote: “This is how life becomes nothing and disappears. Automization eats up things, clothes, furniture, your wife and the fear of war.”[5] In the century that followed, social observers like Jacques Ellul, Marshall McLuhan, Neil Postman, and many others articulated deep concern about the ways in which a coming technological and digital age would alter human experience. That day has arrived and with unprecedented existential force. Vouchsafing our humanity has never been more urgent!

How then to be human when nearly every economic future and power structure seems pitched against it? It’s an immense question, one that outpaces my wisdom. But in the spirit of this essay, I offer two encouragements. First, artists can help redress the challenge of our late modern moment. Our creative labors occur in proximate times and places, and I believe that our acts of material making present a counter offensive to the steady advance of consumer capitalism. The privilege of making a painting or chair, drafting a musical score or poem, producing a film or loaf of bread, restores human pace and scale to our lives. Returning to Shklovsky, “and so, what we call art exists in order to give back the sensation of life, in order to make us feel things, in order to make the stone stony.” Artists cannot save the world. But deep and wide, we can generate some of the beauty our hungry souls desire. So let us play in ten thousand places.

Cameron Anderson, Roi

mixed media assemblage (2025)

Prompted by Roi, my second encouragement is to study the man Jesus. Right now, a lot is happening in the world in the name of Christianity. But notice how seldom these aggressive endeavors (even in the church) bear any resemblance to Jesus’ life and teaching: Don’t be anxious about today. Don’t build big barns to hoard your wealth. Lose your life, if you hope to save it. Love God. Love your neighbor. Though it was not my intention, making Roi and drafting this essay in this season became a Lenten reflection: behold the man who is the radical exemplar of what it means to be human.

Notes:

[1] I am having some fun here juxtaposing the figure in my sculpture to the profane king in Alfred Jarry’s disruptive French play Ubu Roi (New York: New Directions, 1961). The play, first performed in Paris on December 10, 1986, prefigures the Dadaist and Surrealist movements.

[2] Chloe Aridjis, The Spirit Level (Madrid: Loewe Foundation, 2023), 74-75.

[3] Aridjis, 75.

[4] Betty Spackman, A Profound Weakness: Christians & Kitsch (Manchester, UK: Piquant, 2005).

[5] I thank Sharon Hale for this citation. Viktor Shklovsky, “Art as Device,” Viktor Shklovsky: A Reader, ed. and trans. Alexandra Berlina(New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2017), 80.

[6] Gerard Manley Hopkins, “As Kingfishers Catch Fire,” Gerard Manley Hopkins: Poems and Prose (1953, London: Penguin, 1985), 51.