Easing north on Highway 141 through Wausaukee, Wisconsin (pop. 594), I never fail to notice Eden Restored. Unlike the 16th-century embroidered textile pictured above, this single-story shop clad in tan vinyl siding hardly signals Paradise.[1] Its health market offers bulk tea, natural oils and supplements; and its lifestyle center a hyperbaric chamber, near infrared light panel, and sauna. Despite these offerings, in summer months, it’s the Ice Cream Station on the west side of the highway that boasts long lines and crowded outdoor tables.

It may seem odd to start an Advent meditation this way. With an opening scene headed north one could rather imagine a cold winter’s night, the first dusting of snow, and a stall in some empty barn (there are plenty) where the Christ Child might be born. But we begin our Advent watch with the proprietor of Eden Restored. For do we not share her sense that, in some primeval age, there was a Paradise? Do we not also long for Eden restored?

I know that ache each spring with the early burst of crocuses in our lawn. I sense it mid-summer when the fireflies blink about our backyard. That longing returns in autumn as spirited sparrows cavort in our privet hedge. Even in bleak mid-winter, notions of Paradise hold fast. For me, the most poignant anthem of this longing resides in the lyrics Joni Mitchell’s lyrics: “We are stardust, we are golden. We are billion-year-old carbon, and we got to get ourselves back to the garden.”

The opening chapters of Genesis remind us that, “The LORD God took the man and put him in the garden of Eden to till and keep it.” But beguiled by the cunning serpent, the Garden’s first gardeners elected to eat of the fruit forbidden them. God could not abide their rebellion and Adam and Eve were banished from the Garden. To prevent their return, winged Cherubim brandishing a flaming sword keep watch at its gate.

Revisiting this familiar story yields several surprises. Consider, for instance, the possibility that only four beingss have ever known the Garden’s verdance and communion firsthand: God, its maker; Adam and Eve, its residents; and the interloping serpent. To all others and across all time it remains a secret garden.

And consider this: although Adam and Eve were sent away from the Garden, neither Testament mentions God’s departure. An omnipresent God is not bound to any particular place, of course, no less one of his own making. But Genesis confirms that Adam and Eve, “heard the sound of the LORD God walking in the garden at the time of the evening breeze.” Again and again, Scripture reports that God visits his created order, that he tabernacled with his people in Eden, Sinai, and Bethlehem. Do we long for Eden because its Divine Creator is eternally present there?

There is more. The biblical story begins in God’s Garden and concludes in God’s City; the New Jerusalem. John’s revelation describes that city as a perfect cube measuring 12,000 stadia on every side. Unlike Babel, the divine metropolis need not reach toward heaven since the very glory of God is already contained within. God’s throne rests at the center of God’s City and a river flows from it. Trees of Life line the banks of that river and the leaves they bear are for the healing of the nations. Could it be that God erected his City to feature his Garden?

Finally: if the reality of God’s Garden transcends all time and space and if he remains present there, perhaps God’s Gardener—the one whom Mary Magdalene met as the first to witness the resurrected Christ—can lead us back?

This Advent, watch for him, the Son of Man who has and will come, the one who will greet us at the Garden’s gate, the only one who can lead us in.

Notes:

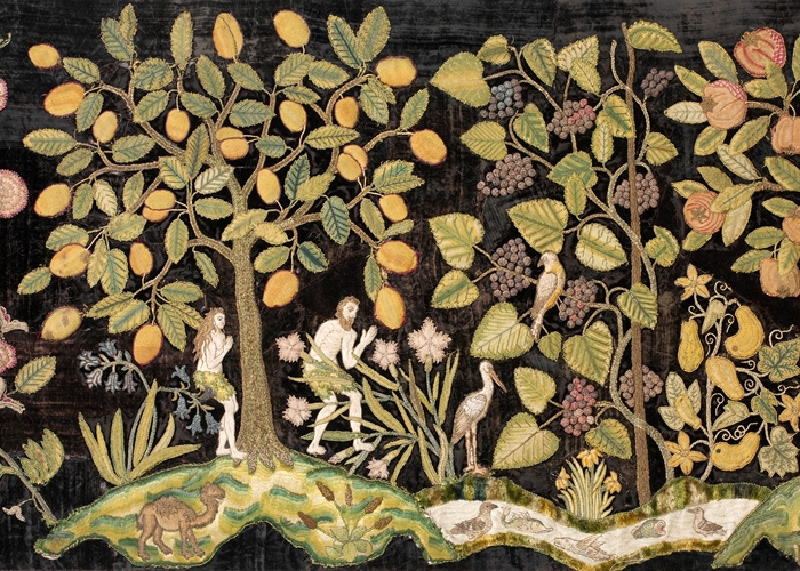

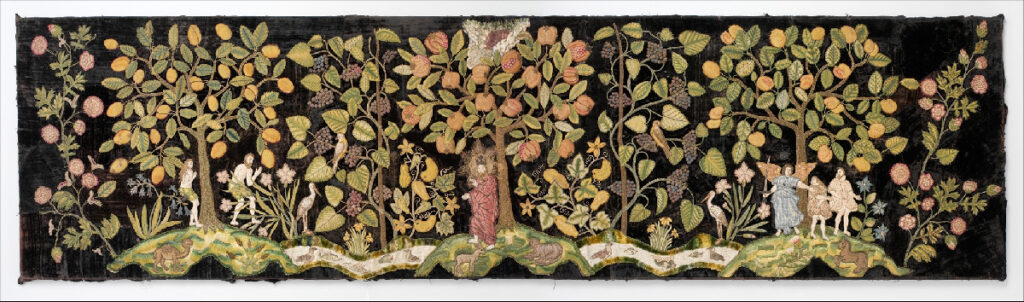

[1] “This panel was one of a set of three valances probably used to decorate the tester of a bed. Small elements—fruits, flowers, and leaves—were worked in tent stitch on canvas and then applied to the dark velvet foundation on which was worked the river in the Garden of Eden, the figures of Adam and Eve, and God the Father, in polychrome silk and metal threads.” Anonymous, late 16th-Century British Tapestry, Collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

This essay first appeared on December 1, 2024 in the Advent Project 2024, an online publication of Christianity, Culture & the Arts and Biola University.