Notes from the Studio

At age twelve I asked my father if I might have a drawer in his filing cabinet. I imagined gathering all my things and ideas . . . shoebox collections, roadmaps, summer camp mementoes, clippings from LIFE Magazine . . . in one place. For even then I sensed that the world’s small wonders and bits of knowledge added up to something. He agreed that the second drawer from the top, including its fistful of army-green hanging files, would be mine. Although my aspiration to organize the universe was short-lived, that same impulse led me to become a junior philatelist. Through middle school and beyond I devoted many hours to soaking canceled stamps, pressing them between volumes of our World Book Encyclopedia, and mounting wild birds, prime ministers, and their far-flung countries in neat rows.

Why does a child comb for shells and pebbles, then line them along the sill of her bedroom window? Why gather marbles in a jar or a clutch of bracelets on one’s wrist? Fitting found things together makes a big world sensible. This movement toward order is primal. Beasts and birds create habitats and abide seasonal rhythms. Homo sapiens pursues this same ordering, but with unusual zeal — a desire, I take it, inherited from our first parents who were tasked to name the creatures.

The second creation account reads, “out of the ground the LORD God formed every animal of the field and every bird of the air, and brought them to the man to see what he would call them; and whatever the man called each living creature, that was its name.” (Gen 2:19 NRSV) A few million species needed names. The mammals and birds, so also fish and reptiles, one assumes, as well as the many plants, trees, and flowers. The natural sciences are born from the Divine instruction to name these myriads. Does not beauty, art’s lifeblood, invite the same? All this sorting of creation’s mystery, the music of the Spheres.[1]

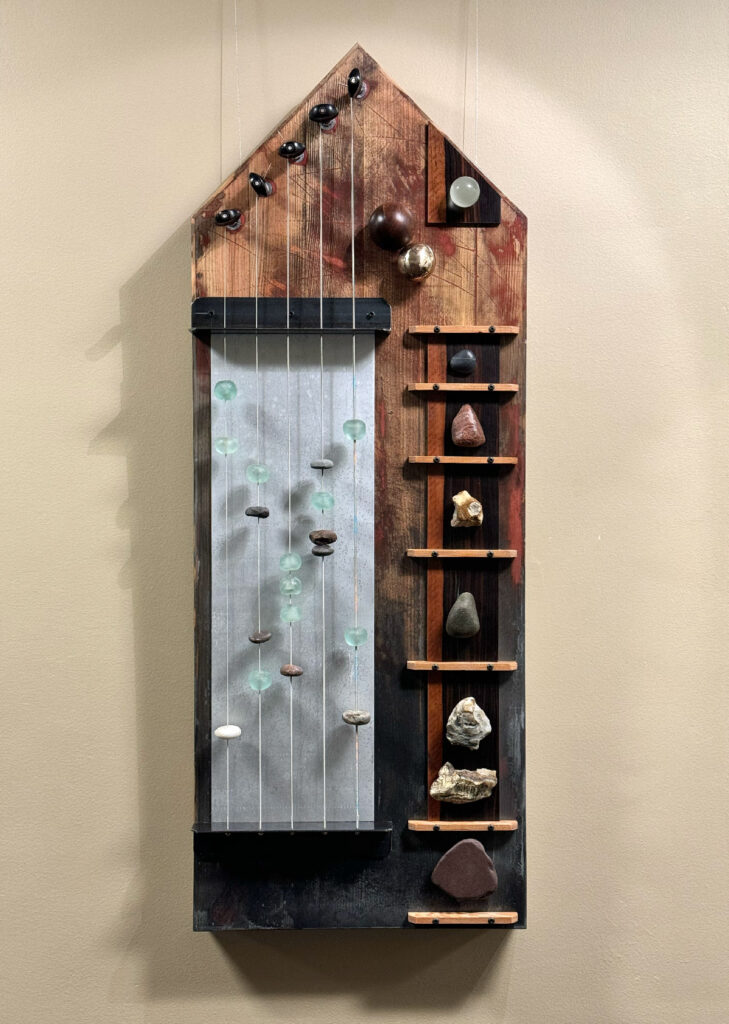

Recently I completed a new piece, The Glass Bead Game (Homage to Hesse). The title taken directly from a Hermann Hesse novel published in 1943. As one friend righty cajoles, mine is a kind of “hardware store aesthetic.” In my studio I am surrounded by assorted lengths of wood and steel, cans of Rust-Oleum enamel, Minwax varnishes, Bulls Eye shellac, and a surplus of found objects. In this milieu abstract notions gain material form. I am the maker of little universes ever lingering at the edge of my mind’s eye, objects and spaces like Joseph Cornell’s boxes, Alberto Giacometti’s The Palace at 4 a.m., and Isamu Noguchi’s remarkable gardens and plazas.

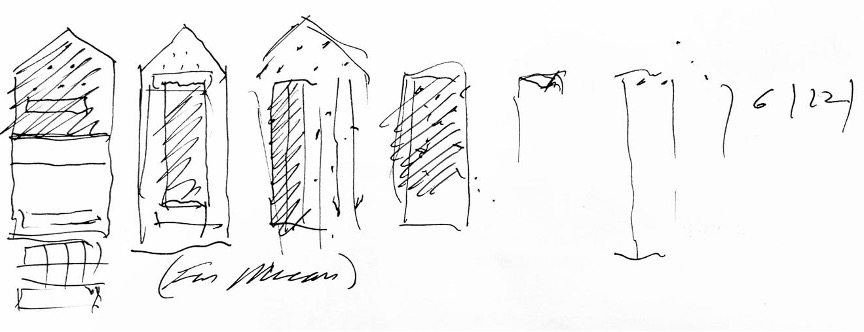

A few rough sketches in hand, a season of hunting and gathering for the piece commenced. I retrieved a slice of rosewood veneer, a bronze ball cast many years ago, and a mahogany sphere l had turned on a lathe. I purchased turquoise glass beads and ebony tuning pegs on Etsy and bass guitar strings at a local music store. And yes, repeated trips to Ace Hardware. Spread before me then, a puzzle of ratios, shapes, and patinas that, as homage to Hesse, needed fitting together.

The backstory to my fascination with Swiss German writer Hermann Hesse began in my late teens. I was caught up in the counterculture, a season in American life rife with political revolution, music festivals, and underground newspapers. In the words of singer songwriter Paul Simon, we had all gone “to search for America.” I began eagerly reading everything from Richard Brautigan to Albert Camus and “Bucky” Fuller to Jacques Ellul. But Hesse’s novels struck a special chord. I was not alone. The youth culture’s appetite for titles like Demian (1919), Siddhartha (1922), and Steppenwolf (1927) was voracious. It found Hesse’s coming of age tales compelling, made more exotic by his fascination with Eastern spirituality. Although Hesse was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1946, interest in his work waned until the early ‘70s when and due to the rapt interest of the counterculture, his reputation enjoyed a stunning renaissance.

Considered his summa, Hesse spent eleven years writing The Glass Bead Game, the last of his nine novels.[2] By Providence, I settled into my Christian beliefs early on and was not a religious seeker at this time in my life. Nonetheless the premise of Hesse’s novel lit me up! The setting for the story is Castalia, an imaginary European province in some distant, perhaps post-apocalyptic, future. The devastation of WWII and Hitler’s rise to power—during which Hesse wrote the novel—is long past and a group of gifted scholars has gathered to train teachers and to play the Glass Bead Game. Ralph Freedman suggests that, “The game is brilliantly conceived as a ceremony both mystical and rational—a secular sacrament.”[3] A small group of intellectuals and artists devote themselves to the study of mathematics, linguistics, philosophy, art history, and Western Classical music. The task of this community—one modeled after a Medieval monastery—is to discover and preserve the best of the human mind and spirit.

The story’s central character is Joseph Hecht, a young Hesse-like prodigy. At age twenty-four, Joseph graduates and begins his years of free study. During those years Hecht learned to play Glass Bead Game and as he did its significance fell on him full force:

I suddenly realized that in the language, or at any rate in the spirit of the Glass Bead Game, everything actually was all-meaningful, that every symbol and combination of symbols led not hither and yon, not to single examples, experiments, and proofs, but into the center, the mystery and innermost heart of the world, into primal knowledge. Every transition from major to minor in a sonata, every transformation of a myth or a religious cult, every classical or artistic formulation was, I realized in that flashing moment, if seen with a truly meditative mind, nothing but a direct route into the interior of the cosmic mystery, where in the alternation between inhaling and exhaling, between heaven and earth, between Yin and Yang, holiness is forever being created.[4]

After years of studious preparation and broad travels, Hecht becomes the community’s esteemed leader, its Magister Ludi (lat. master of the game). But near the end of the novel, the story takes a surprising turn; Hecht leaves his community to embrace a higher calling, but also a darker fate.

Curiously, Hesse does not supply a description of the actual game nor instructions for how it was played. On first reading about The Glass Bead Game I imagined it to be something akin to a three dimensional chess board. It was that absence of description and instruction that opened my mind’s eye to the possibility of ordering curiosities, ideas, and geometries into some kind of whole. The possibility of gathering all things and ideas and fixing them in some neat row; if you will, lining a window’s sill with small treasures. Recently I learned, “That the ‘inventor’ of the Game [in the novel], Bastian Perrot of Calw, got his name from Heinrich Perrot, the owner of the machine shop where Hesse once worked for a year after he dropped out of school.”[5] Apparently that shop and its oily labors had been, for young Hermann, spiritually evocative.

Invariably, autobiography shapes the dramatic arc of Hesse’s stories. His maternal grandfather, Hermann Gundert, was a celebrated Christian scholar, linguist, and missionary to India. In 1877 grandson Hermann Karl Hesse was born to Johannes and Marie Hesse. “Both Johannes and Marie, besides being devoted Pietists, also had ambitious literary tastes and intellectual curiosity. Johannes eventually assumed the position of director at the Basel Mission Society in 1893, however his intellectual interests remained wide and varied, extending to Latin literature, Greek philosophies, and Oriental religions. Marie also pursued her literary interests, writing biographies . . . and mastering four or five languages in between filling the duties of wife, mother, and daughter and attending endless prayer meetings.”[6]

Young Hermann was precocious, irascible, and at one point even suicidal. His parents struggled desperately to raise him as he abandoned their piety, though on one occasion he did offer that his parent’s, “Christianity, one not preached but lived, was the strongest of the powers that shaped and moulded me.” Regarding religion, Hesse was syncretistic, comfortably assembling and reassembling spiritual histories and beliefs to suit his purposes. And, given his upbringing, Hermann’s attraction to Eastern spirituality might seem preordained. Other formative experiences included an unhappy year of study at Maulbronn Seminary (Hesse completed no academic degrees), a pilgrimage to India, ongoing Jungian analysis, and three marriages, first Maria, then Ruth, and finally Ninon. A neo-romantic poet and painter, Hesse preferred the serenity of rural life and until his death in 1962, was a man of letters.

Hesse’s Castalia and its Glass Bead Game are fictions. But we are drawn to them because in our better cultural moments Castalian-like communities do gather: sometimes in universities and seminaries, also in music conservatories, museums, writing groups, and artist colonies. Hesse’s vision is best realized for me in the community of friends, old and new, with whom I travel. And in the end, I stand by my childhood sense that the world’s small wonders and bits of knowledge cohere. They are a foretaste of the holy unfolding built into a cosmos that is filled to the brim with named beings and things. These were my thoughts as I gathered things, measured their meaning, and fashioned The Glass Bead (Homage to Hesse).

Notes:

[1] Cameron J. Anderson, “The Music of the Spheres,” The Faithful Artist (Downers Gove, IL: IVP Academic, 2016), 199-226.

[2] Hermann Hesse, The Glass Bead Game, trans. Richard and Clara Winston, for. Theodore Ziolkowski (New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston), 110. Hesse’s two-volume work, originally Das Glasperlenspiel and published in Switzerland, was first translated into English in 1949 by Mervyn Savillas as Magister Ludi.

[3] Ralph Freedman, “The Glass Bead Game,” New York Times Archives, January 4, 1970.

[4] Hesse, The Glass Bead Game, 110, 119.

[5] Theodore Ziolkowski, in Hesse, The Glass Bead Game, ix.

[6] J. Sobel, Hermann Hesse: Background, Childhood, and Youth (1977-1895), May 2, 1997.