Eager to support artists in Ukraine, Professor Richard Cummings had an idea. He curated an exhibit entitled We Are Together: Icons of Hope and invited twenty-one artists like Sandra Bowden, Bruce Herman, Sedrick Huckaby, Tim Lowly, Steve Prince, Delro Rosco, Ned Bustard, and others to donate work. I gladly contributed Light in the Vault and Dazzling Darkness.

Light in the Vault, 12 x 12 inches, silver enamel and orange shellac on oak.

Dazzling Darkness, 12 x 12 inches, black and silver enamel, and red lacquer putty on charred oak.

We Are Together opened on March 19, 2024, in Boger Gallery at the College of the Ozarks, where Richard teaches. The show will travel on to Lviv to encourage local artists, and proceeds from the sale of the artwork will be used to establish a benevolence fund for contemporary icon painters in Western Ukraine. To launch the project, Cummings produced a striking limited-edition print entitled Christ is Here (Xpnctoc tyt), pictured in the header of this post. Describing the layers of symbolism in this piece, he explains:

The city skyline of Lviv is reflected in the blood of Christ who, having shared in our human sufferings, feels the pain of a suffering nation and its people. Malevich’s iconic Black Square painting [1] became the cracked and spoiled ground of war over which God is still sovereign, and the gold throughout the piece provides a sense of hope and reflects the radiance of the promised New Creation.

Richard’s thoughtful exhibit and compelling print summoned two reflections: the first having to do with the shifting meaning of the term “icon,” the second our urgent need for hope.

In our time, “icon” or “iconic” is a ubiquitous term deployed at will to signify any number of things. But in popular usage it mostly refers to a celebrated public figure or pixilated tile on a digital device. Religious-minded folks, especially Orthodox Christians or students of art history, will be quick to observe these don’t signal the sacred; they don’t point to a Holy Other.

Lifelong, the world of religious icons has seemed mostly foreign to me. Here is why. The focus of my undergraduate and graduate training was modern and contemporary art. Sacred art made cameo appearances in some art history classes, but in the artworld, so-called Christian dogma was mostly flagged as the enemy of personal expressive freedom. Meanwhile, the Bible-believing churches that nurtured my spiritual life mostly disdained religious images. The B.I.B.L.E. (as the children’s chorus went) was all we needed in faith and in life. Never mind that Jesus, the Word, had become the brilliant Icon (image) of God.

In 1990 a short essay by William Safire helped me locate the function of the term icon in contemporary life. “Now, in this time of symbol-fascination, icon is being worked harder by people who have tired of using metaphor as a voguish substitute for paradigm, model, archetype, standard or beau ideal,” wrote Safire. “The word’s meaning is now ‘cherished symbol’ extended beyond religion.”[2] Earlier usages of the term icon had been radically repurposed; for the most part, it no longer referred to a carefully rendered object generated by a prayerful icon writer to deepen the devotion of a pious supplicant.

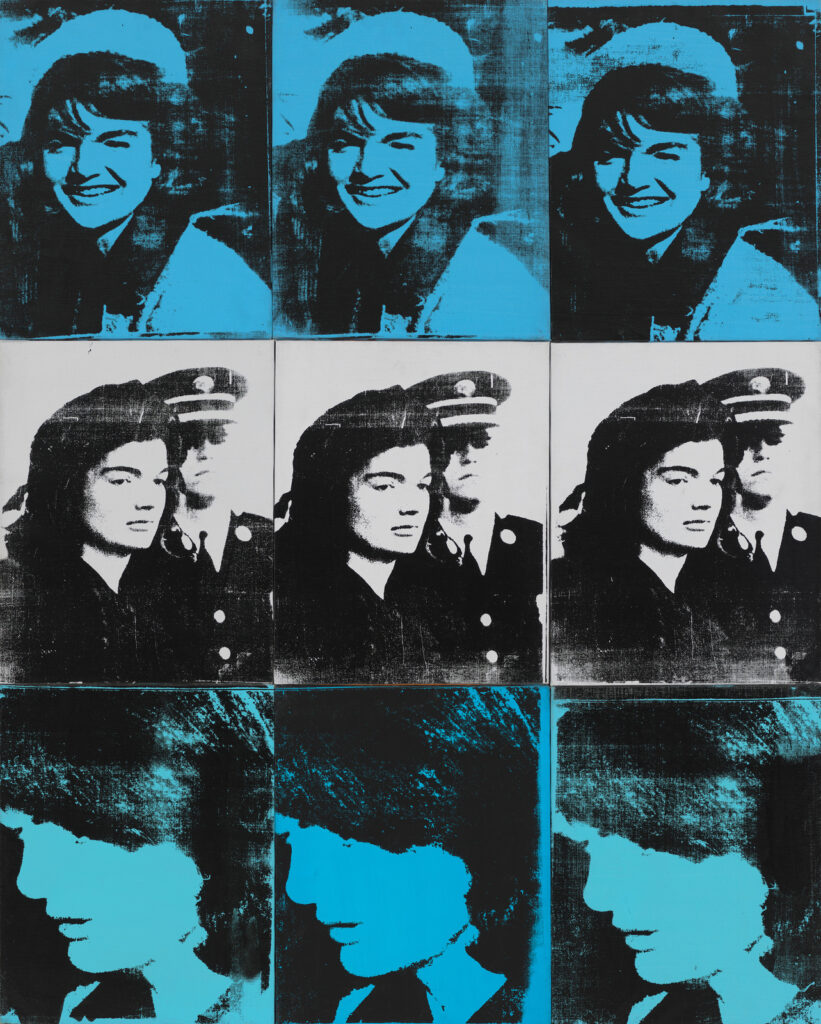

Decades before Safire’s column, Pop Artist Andy Warhol—a brilliant designer and colorist—understood that image is everything. In the 1960s he began appropriating images of Mao, Marilyn, Jackie, and Elvis from tabloids and fanzines, re-presenting them to viewers as memorable visual icons. A deeper look reveals something more: the celebrities Warhol depicted were often burdened by tragedy. Andy was himself such a figure. As much as any, this tragic sense appears in his work Nine Jackies (1964), a piece from a series he produced months after the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, Jackie’s husband.

As suggested, today’s icons point in two directions. In the first instance, they confer godlike status to the powerful, beautiful, and famous. That was Warhol’s visual pantheon. Today it’s Barbie, Taylor, LeBron, and Trump—each a demigod to loyal fans. Second and more subtle, the icon now exists to do our bidding. Click your mouse (make a command) on a small graphic symbol for Capital One, West Elm, or Domino’s, and move thousands of dollars in a millisecond, arrange next-day delivery of a leather chair, or order a pizza for halftime. In service to pleasure and efficiency these pixelations function like portals to the land-of-no-limits, regulated only by available cash or credit.

The new icons, call them celebrity and agency, outpace the old. Go ahead, pray to a sacred icon and what? Nothing. Silence. Do the old ones get you anywhere? Do they deliver anything? The new ones bear our image and do our bidding. I know, it’s not that simple. But the move from old to new has occurred at breakneck speed, and sometimes the new icons swiftly take you to very dark places. Meanwhile the incremental erasure of transcendence is barely perceived.

The strength of Cummings’ Christ is Here print is its appropriation of a late sixth-century icon, Christ Pantocrator. Richard’s artwork is not an icon in the traditional sense: his image is printed, not painted (icon makers refer to their work as writing); its metallic surface shimmers but is not goldleaf; and it does not closely adhere to a particular iconographic program. But this departure allows Cummings’ piece to function as a religious icon for our moment. It builds on that deeper tradition to present us with the powerful image of the King of Heaven. A golden nimbus surrounding his head, the wise teacher sits above an inverted image of Lviv’s blood-red, spired cityscape and his fierce gaze meets ours. How will we respond to the devastation of Ukraine, its culture, and people?

Second, a thought or two about hope. From Vietnam in the 1960s to present-day Gaza, I am weary of violence and war—the killing of countless innocents, the plundering of homeplaces, the senseless destruction of fertile lands and cultures. Listen to the psalmist:

Too long have I had my dwelling

among those who hate peace.

I am for peace,

but when I speak,

they are for war. (Ps 120:6-7)

Vladimir Putin is a modern icon but an autocrat with a dead soul. What childhood wound or maniacal obsession made this man? I cannot say. But the world knows that Putin’s appetite for violence and conquest is insatiable. He believes that Russia’s greatness and his requires the subjugation of every other power.

In the negative, this vacuum of virtue, Putin’s atrophied heart points to the single ethic that could liberate the entire world: consider others more highly than yourself. This is not our natural state. But imagine a world where most of our energy is given to help others survive, then thrive. And notice that the virtue of other-centeredness is what our best mentors, spiritual directors, and parents possess. They laud the achievements of the very ones who may one day surpass them; the success of their mentees, disciples, and children is their greatest delight. This kind of ecology is easily voiced but difficult to achieve. It is radical in the truest sense. Jesus taught, “to gain your life, you must lose it.”

Ending where I began, Professor Cummings has more to teach us. After the intense labor of launching the We Are Together: Icons of Hope exhibit, Cummings gave himself to one more task. In a letter sent to each artist who donated work to the Ukraine exhibit, he wrote: “I would like you all to know how incredibly grateful I am for your participation in this project. I am overwhelmed by your generosity and by your outpouring of support for the people of Ukraine and for the Ukrainian artists. To show my gratitude, I have made an edition of 50 of my prints, Christ is Here (Xpnctoc tyt).” With the letter, each of us received a numbered and signed print.

So far as I know there is no calculus wherein beautiful gestures cancel acts of violence. But the beauty of Richard’s project is that he chooses hope. He exercised his agency to take action, to do his part, to offer what artists have to give: our creative spirits and the work of our hands. But when I received Richard’s, I understood something more: he distributed gifts to those who had already given. His gesture was at once the gift of a beautiful object and the gift of a beautiful act. Lewis Hyde writes, “Sometimes, then, if we are awake, if the artist really was gifted, the work will induce a moment of grace, a communion, a period during which we too know the hidden coherence of our being and feel the fullness of our lives.”[3]

Note: In support of the We Are Together project, original unframed copies of Richard’s print Christ is Here (Xpnctoc tyt) are available for $150. I encourage you to contact him at bogergallery@cofo.edu for details.

Notes:

[1] Kazimir Malevich painted Black Square in 1915. A leading artist in the Russian avant-garde and founder of the Suprematist art movement, Malevich was born in today’s Ukraine. His goal was to move art away from copying nature and toward pure abstraction, and he employed geometric forms to do so.

[2] William Safire, “I like Icon,” The New York Times Magazine (February 4, 1990), VI: 12.

[3] Lewis Hyde, The Gift: Creativity and the Artist in the Modern World (New York: Vintage Books, 2007), 196.