By Cameron Anderson

Then I considered all that my hands had done and the toil I had spent in doing it, and again, all was vanity and a chasing after the wind, and there was nothing to be gained under the sun.

—Ecclesiastes 2:11

From birth, Bible-believing churches had been my spiritual home, but when I headed off to college and then graduate school to study visual art, I chose secular institutions. During those years, the prospect of sorting out the relationship between my deeply held faith and a growing passion for art intrigued me. It is also churned considerable self-doubt. [1] A few years after completing my M.F.A., I discovered Madeline L’Engle’s Walking on Water: Reflections on Faith and Art. One sentence in the opening pages of her book was particularly arresting:

“To try to talk about art and about Christianity is for me one and the same thing, and it means attempting to share the meaning of my life, what gives it, for me, its tragedy and its glory.” [2]

L’Engle’s declaration allows for suffering and beauty to coexist, and it came to be that my spiritual formation and studio practice would engage this same tension lifelong.

This blog is the third of a four-part series that examines the meaning of God’s garden in Eden, that place where, according to the Christian story, human history commences, and the beginning of God’s grand theological narrative is revealed. If the two creation accounts in Genesis 1-2 extol God’s creative power and the glory of his creation, the record of Adam and Eve’s disobedience in Genesis 3 reveals the story’s tragedy. Following the breathtaking declaration at the end of Genesis 2, “And the man and his wife were both naked and were not unashamed,” the fall of the man and the woman from their original state of grace unfolds and in two discourses. The cunning serpent initiates the first (3:1-7).

Who is this despicable creature that appears in the garden unannounced? The text supplies no answer. What it does report is that he proceeds directly to interrogate the woman and challenge God’s earlier command. “Did God say, ‘You shall not eat of any tree in the Garden?,’” he asks (3:1b). In fact, God had intended for the man and the woman to eat of every tree in the garden, save one. The woman corrects the serpent’s false claim by reciting God’s prohibition verbatim (3:2-3). Determined to overturn God’s authority, the serpent then circumvents rational argument and appeals to desire. He invites the woman to doubt God’s command by misstating it, piques her curiosity regarding the fruit’s possible benefits, and intensifies her longing. She knew this fruit was forbidden, but now she is learning that it might be good to eat, a delight to her eye, and could even make her wise. Resisting its allure seemed impossible.

In Eden’s garden, LORD God was the perfect host. There the man and woman enjoyed remarkable freedom, though it was never unbounded. The first creation account in Genesis records God’s unqualified declaration that everything he has made is good, very good. But it did not follow that everything in the garden was good for the humans. The second account contains God’s clear warning that the man and the woman must neither touch nor eat fruit from the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, “For in the day that you eat of it you shall die” (2:17). Beyond any measure of doubt, they knew that they were disallowed from eating fruit from that tree. Even so, the woman partakes and invites her husband to do the same. “Then the eyes of both were opened and they knew that they were naked” (7a).

Two further observations warrant mention. First, Eve’s desire is present to her in her state of innocence. Notice that human desire is not inherently evil, rather, like the senses that so often trigger it, it must be regarded as good. Desire’s challenge is always its object. We may long to know God, but we may also desire to harm an enemy. Second, Eve’s desire must considered as separate from her act of rebellion. Her decision to touch, take, and eat the fruit was volitional.

LORD God initiates the second discourse (3:8-19). Like the serpent, he too enters the garden, but expects to meet both the man and his wife “at the time of the evening breeze.” On hearing him approach, they hid among the trees. If the serpent had met Eve in her innocent state, God now approaches the pair in their fear and shame. Like physical actions, moral and spiritual decisions have consequences and as this second discourse continues, God’s curse falls hard on the serpent, then the woman, and then the man (3:14-19).

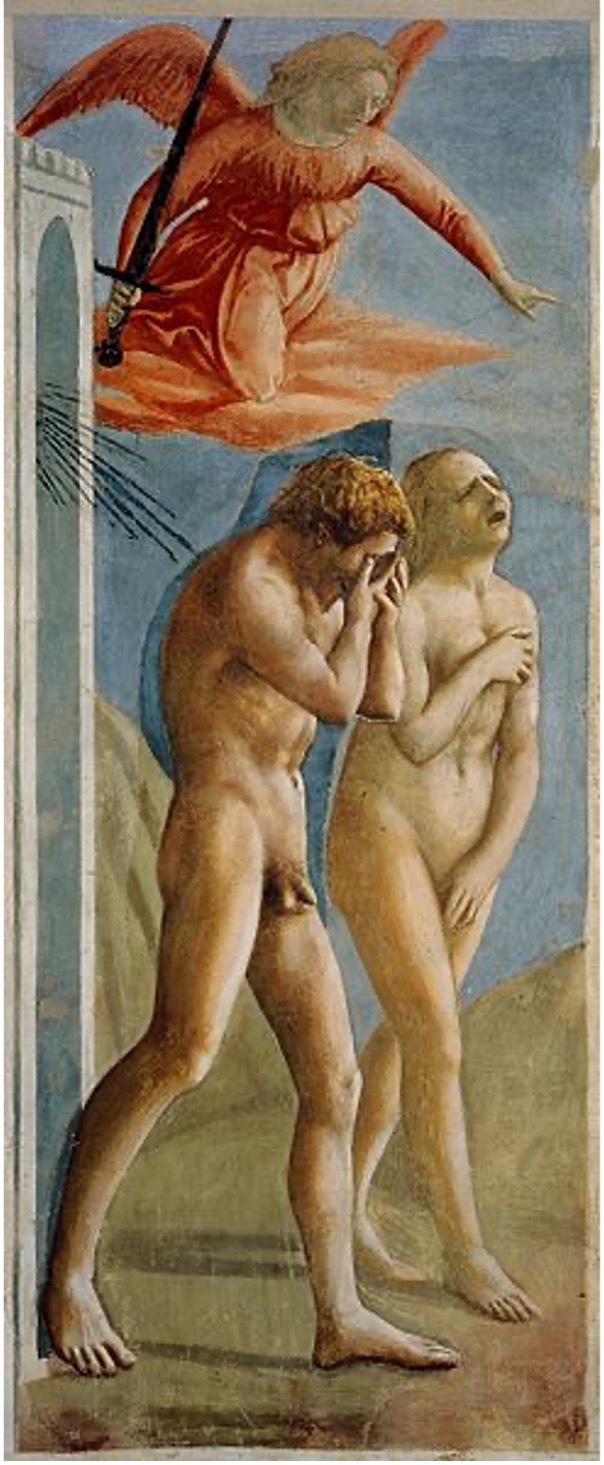

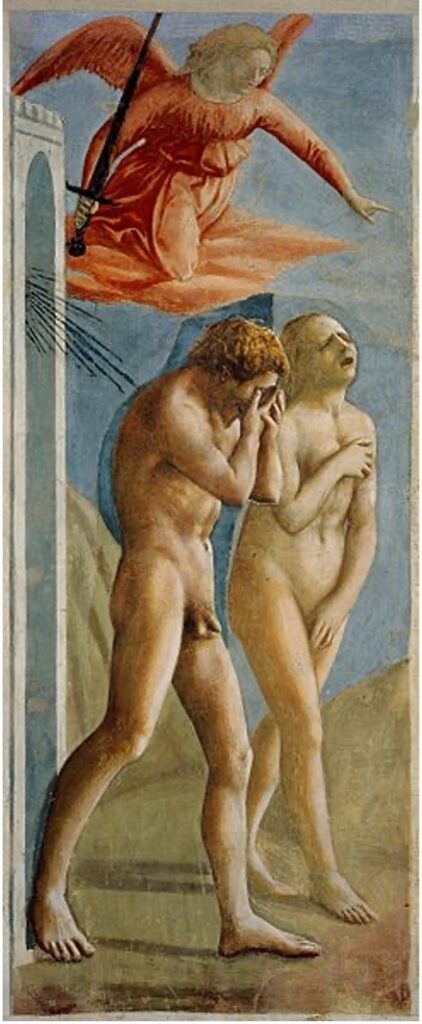

Masaccio’s Expulsion from the Garden (c. 1475) is a haunting depiction of that moment. It is the left-most panel in a larger fresco cycle located in the Brancacci Chapel inside the church of Santa Maria del Carmine in Florence. In Masaccio’s rendering, Eve’s hands cover her nakedness and her head tilts backward in despair. She is overcome with grief. By contrast, Adam’s hands cover his face, as his head bow beneath the weight of shame. Now banished from Eden, the garden’s gate stands behind them and God places “the cherubim, and a sword flaming and turning to guard the way to the tree of life” (3:24). Now they must create a life apart from the garden’s abundance. And for the first time, the life-giving work God had given them to do will encounter futility. The prospect they face is life with no telos.

Adam and Eve’s disobedience entirely disrupts the order of Eden. But could the whole of human history be altered by one women taking but one bite of one piece of forbidden fruit? This is a profound and consequential theological question.

What we can say is that the central principle of Christian piety holds: if there is a Creator God, then the wise woman or man will align his or her life to the material, moral, and spiritual design of his world. When we determine that we are better off without God, this ancient story becomes modern in every way. The point of the narrative is this, contained in this first act of rebellion is the whole of humankind’s desire to experience the forbidden and then to possess it. Life lived apart from God is the foundation of all human misery, and spiritual death is its outcome.

It takes but a little living to encounter the world as a fraught place. Arguments at home, annoying classmates or colleagues, difficult neighbors. Not to mention wars and revolutions raging around the globe. The list of human maladies and struggles, its own dark liturgy, is long. Hunger, homelessness, disease, and environmental degradation are ever present. For millennia, brilliant minds and generous hearts have sought to quell the impact of human evil. Even so, our baser nature prevails and, on occasion, even those seeking to guard the flame and keep the vision, succumb to it.

The opening chapters of Genesis record humankind’s movement from fidelity to infidelity, from life lived in the garden under God’s blessing to life lived east of Eden beneath his curse. This movement is captured in at least five binary pairs: truth and deceit; abundance and scarcity, presence and absence; and life and death. The contemporary mind is inclined to regard binaries as uncommonly harsh. We seek toleration, not absolutes. We prefer more nuanced private and public worlds. We inhabit the liminality that exists between these polarities. Perhaps some admixture of novel understanding, vulnerability, and emancipation will lead us to the good life? Perhaps it is freedom expressed as self-determination that we seek, but this existential scaffolding is not so sturdy. Besides, some bear wounds so deep they cannot be comprehended, they live for darkness, if only unwittingly. And then there is the condition of our own hearts, our malformed egos, our interior fragility, and our acting out. The hallmark of fidelity is presence and obedience, the evidence of infidelity is absence and self-emancipation.

Deep in the human soul is a longing to return to Eden’s garden, to recover what has been lost. Driven from the garden, Eden’s abundance and pleasure was no longer available to Adam and Eve. Neither is it available to us. How then shall we understand our origin and destiny if we cannot return home? Do we not, on occasion, sense the reality of God’s Paradise in art, or friendship, or worship? Do we not, in those moments, draw near? In every good homecoming, there is some sense of this. But we cannot return, not yet. Until then we pray as Jesus taught us: “Your kingdom come, your will be done, on earth as it is in heaven.”

Notes:

[1] The many questions raised during those formative years would become the framework of the book I wrote several decades later, see Cameron J. Anderson, The Faithful Artist: A Vision for Evangelicalism and the Arts (Downers Grove, Illinois: IVP Academic, 2016).

[2] Madeleine L’Engle, Walking on Water: Reflections on Faith and Art (Wheaton, Illinois: Harold Shaw Publishers, 1980), 16.