By Cameron Anderson

The heavens are telling the glory of God;

and the firmament proclaims his handiwork.

Day to day pours forth speech,

and night to night declares knowledge.

—Psalm 19:1-2 (NRSV)

Promoters described the 1969 Woodstock Music and Arts Fair as an “Aquarian Exposition: 3 Days of Peace & Music” and that August more than 400,000 concertgoers swarmed the fields of Max Yasgur’s farm in White Lake, New York to take it in. The festival featured bands and solo artists like Blood, Sweat & Tears, Grateful Dead, Jefferson Airplane, Jimi Hendrix, Joan Baez, Santana, The Who, and a host of others. Although Joni Mitchell did not attend Woodstock, she did write the music and lyrics for the song that famously commemorates the event. Her opening verse captures the spirit of that cultural moment:

I came upon a child of God

He was walking along the road

And I asked him where are you going

And this he told me

I’m going on down to Yasgur’s farm

I’m going to join in a rock ‘n’ roll band

I’m going to camp out on the land

I’m going to try an’ get my soul free

In 1945, Allied powers had defeated Hitler but accompanying this victory was the creation of a powerful military-industrial-complex. In the 1960s Vietnam became the exotic theatre in which that war machine was tested—an ill-advised and prolonged conflict in Southeast Asia that would come to be the “greatest generation’s” worst fruit. As the war raged on, their children demanded an end to the thrall of its greed, violence, and global domination. By the late ‘60s and early ‘70s, America’s youth culture, especially university students, were radicalized. Bitter racial divisions at home coupled with a growing awareness of environmental degradation added to the stress.

Sensing apocalypse on the horizon, the American counterculture yearned for innocence and freedom. In their view, it was time to recover a new vision of peace and harmony, to return to nature and community, to embrace Mother Earth. Mitchell’s refrain speaking of a return to the garden seemed prophetic. The American counterculture was romantic, even naïve, but in concert with Joni’s exquisite folk-rock soprano voice, its members found themselves longing for Eden’s Garden.

The opening chapters of the Hebrew Testament offer two distinct creation accounts; God’s garden is only described in the second. “The Lord God planted a garden in Eden, in the east” (2:8). Reading on we learn that a river flowed out of Eden and into four branches—the Pishon, Gihan, Tigris, and Euphrates—so that the spring from the garden watered the surrounding region in every direction (2:10-14). It was in this garden that God placed the man (2:15). By design, God intended Eden’s garden to be a place of sensorial delight, abounding with all good things. But the more important dimension of this Paradise was that all creatures living there would enjoy the real presence and blessing of God, its maker.

Mitchell was hardly the first to recognize the imprint of the garden-ideal on American consciousness. Sixteenth-century European explorers were overwhelmed by the unsettled beauty and bounty of the New World. It was to them a new Eden; majestic in scope, abundant in resource, and uncorrupted by human habitation.[1] Tragically, their colonization of the land drove out indigenous peoples who had occupied it for millennia. Many White European settlers regarded these First Nations people as heathen tribes in need of conversion to Christianity; total elimination appealed to others—recapitulating the sin of Cain, rather than the garden in its original beauty.

In the centuries that followed, recapitulations of the garden assumed manifold forms. For instance, in 1830 a philosophical movement, Transcendentalism, emerged, primary proponents of which included well-known figures like Henry David Thoreau (1817-1862) and Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803-1882). The movement gained further momentum in the writings of members like Margaret Fuller (1810-1850) and like-minded poet, Walt Whitman (1819-1892). Transcendentalists celebrated the divinity of nature and humanity, the unity of all things, and confidence in the virtues of subjective experience. They were romantics at heart, and often theologically aligned with Unitarianism.

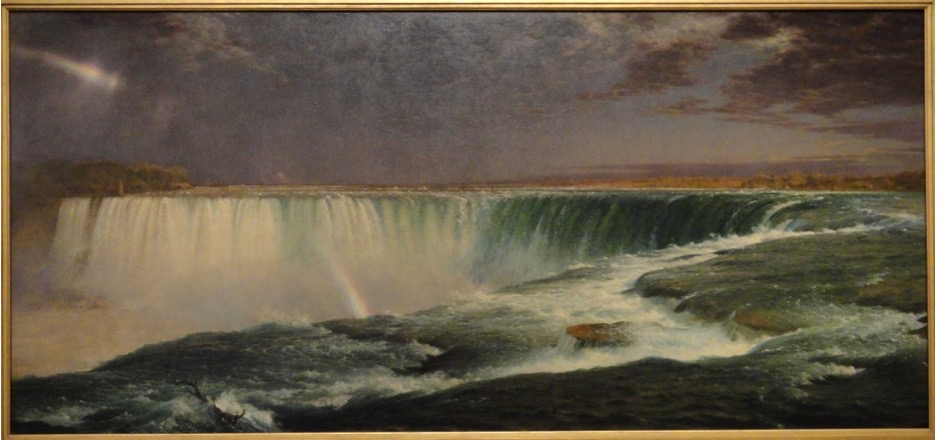

Important pursuits in the visual arts found common cause with the Transcendentalist frame of mind. In the 1850s New York-based landscape painters like Thomas Cole (1801-1848), Frederic Edwin Church (1826-1900), and Albert Bierstadt (1830-1902) formed the Hudson River School and in the decade to follow another related movement, Luminism, took hold. These artists fashioned monumental canvases in an effort to contain grand scenes like the sun rising and setting across panoramic landscapes, mountain peaks, thundering waterfalls like Niagara, and hidden bucolic valleys.

Regard for the natural environment was not the exclusive domain of American philosophers, writers, and artists. As early as 1872 Yellowstone was declared a National Park. By 1892 the Sierra Club had been formed and in 1905, the National Audubon Society. A growing number of citizens were recognizing—and alerting others—that natural habitats and the species they sustained needed protection. Among these was the 26th U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt (1858-1919), who was known as the “conservation president.”

“While in office he protected some 230 million acres of public land, including 51 bird reservations, four wild game preserves, 150 national forests, five national parks and 18 national monuments, including the Grand Canyon national monument.“[2]

President Woodrow Wilson officially established the National Park Service in 1916. The impressive story of these Eden-minded people is recounted in Ken Burns’ 2009, six-part, PBS documentary, The National Parks: America’s Best Idea.[3] Central to this forward-looking vision was the 26th U.S. President.

The research of environmental scientist Cal DeWitt confirms that Roosevelt was a devout Christian man who regularly attended Grace Reformed Church in Washington D.C. His determination to protect enormous tracts of land from rapid development and preserve them for the American people was informed by his reading of the Bible. DeWitt also notes that important naturalists like John Muir (1838-1914), Aldo Leopold (1887-1948), Rachel Carson (1907-1964), and Lynton Keith Caldwell (1913-2006) were all avid Bible readers. [4]

Even as the postwar period was a season of industry and prosperity, evidence of new environmental challenges was accumulating. Universities adjusted their science curricula to explore climate change, rapid population growth, development of vast cosmopolitan centers, and the alarming advance of environmental degradation. In 1970 the Environmental Protection Agency was formed, and the first Earth Day was celebrated—the ‘70s would come to be known as the Environmental Decade.

Fifty years later we are just now coming to understand how complex our Biosphere actually is and what that means of us as inhabitants. Equipped with more understanding, some are committed to become better stewards of this beloved world, but many remain unpersuaded and some even protest.

All that I have written thus far is but a sketch to establish the social, political, aesthetic, and spiritual significance of garden-thinking, all the while recognizing our tenuous connection to it. In modern life, for example, we head out to the country, lake, and sea hoping to recreate. Many of us sense that the natural world can be the only true human home, even though the spectacle and convenience of our built world continues to generate its own kind of awe. Inwardly, we find ourselves longing for the Arcadian ideal, for simple, even rustic places, places of innocence, places of remove, pastoral sites that allow us just to be.[5]

In theological terms, the garden image exists as a picture of fidelity with God. The psalmist insists, the “heavens declare the glory of God” (19:1). In his letter to the Romans, Paul echoes this conviction: “Ever since the creation of the world his eternal power and divine nature, invisible though they are, have been understood and seen through the things he has made” (1:20). As DeWitt explains it, in God’s created order we are best able to see the world through the eye of its maker. The garden, then, not only sustains us but is the site of personal spiritual renewal. When we witness the beginnings of a new day, the glimpse of mystery, any measure of wonder in the ordinary, then we have comprehended something of God’s glory. But there is a tragic corollary to this: when the glory of creation is diminished, so also is the glory of God.

In the end, the music that Mitchell penned and performed at age 25 was correct in at least in two respects. First, while many of the Woodstock generation would not describe themselves, in the orthodox sense, as God’s adopted children, they surely did bear his image. Second, many of us would affirm that our souls long for the garden that God first fashioned. We long to encounter the fidelity, bounty, and wonder it contains. And it seems to me that this longing explains, at least in part, the sense of melancholy that so often lingers. Like Moses, there are moments when we draw near to this land of Promise, even look in on it. That is its own kind of pleasure. But it is also a sign. We will return to Eden’s Garden when the second Adam ushers in the New Heaven and Earth, where we will encounter the beauty and glory that first spoke Eden into being.

Notes:

[1] Steve Nicholls, Paradise Found: Nature in America at the Time of Discovery (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2011).

[2] Calvin B. DeWitt, “The Bible and Environmentalism,” Paul Gutjahr, ed., The Oxford Handbook of the Bible in America (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2017).

[3] Dayton Duncan and Ken Burns, The National Parks: America’s Best Idea, Pap/Map edition (Knopf, 2011).

[4] Calvin B. DeWitt, “The Bible and Environmentalism.”

[5] Aaron Sachs, Arcadian America: The Death and Life of an Environmental Tradition (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2014).