By Cameron Anderson

Especially in recent months it’s been all the fashion to deconstruct one’s faith, to wake up to the Church’s many problems and incongruities and conclude that earlier theological and ecclesial commitments are now inadequate, even mistaken. Amid all of this unraveling, a workshop held at Upper House on Saturday, October 21,stimulated fresh insights.

The day-long event, entitled Beauty for Ashes, was led by visual artist and sculptor Marianne Lettieri. The challenge Marianne presented to each of us was to create a 24-page book and fill it with collaged images and designs. The book’s contents—arranged in three eight-page sections (called “signatures”)—would then be stitched into a spine, held fast between two hard covers. We were to accomplish this feat using only the materials (art papers and leftovers from other projects) and tools contained in a large envelope Marianne had placed on the table before each of us. We were constrained by her selections. Often, artmaking is about solving real problems in real time. The adage, “necessity is the mother of invention” proved true.

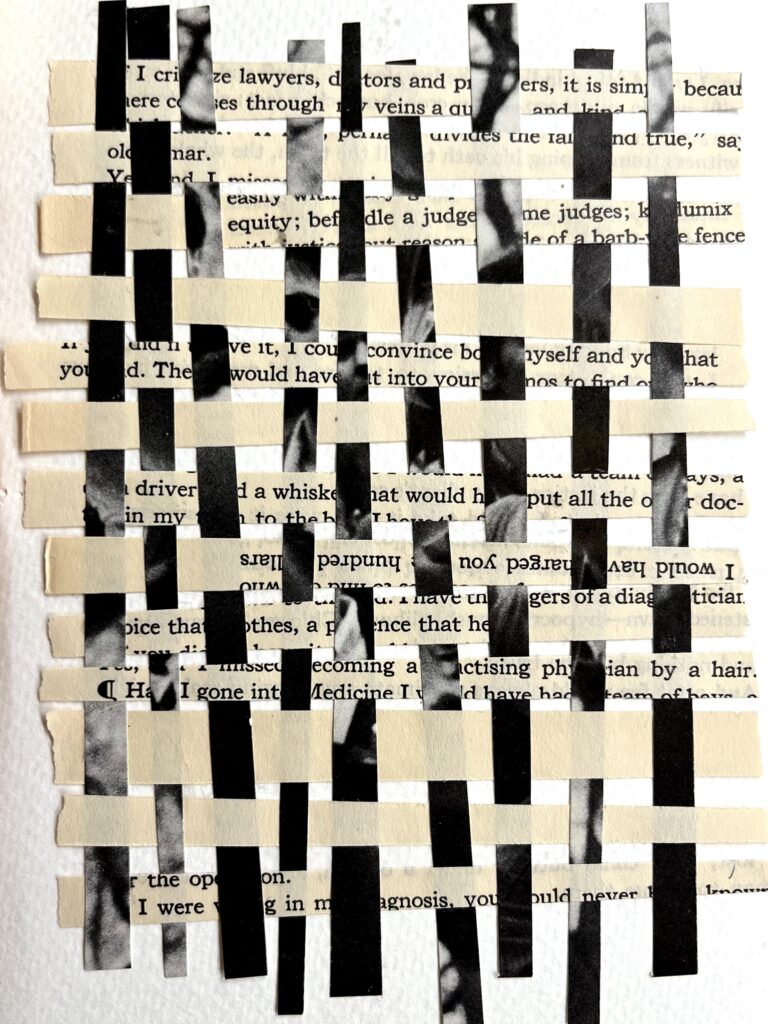

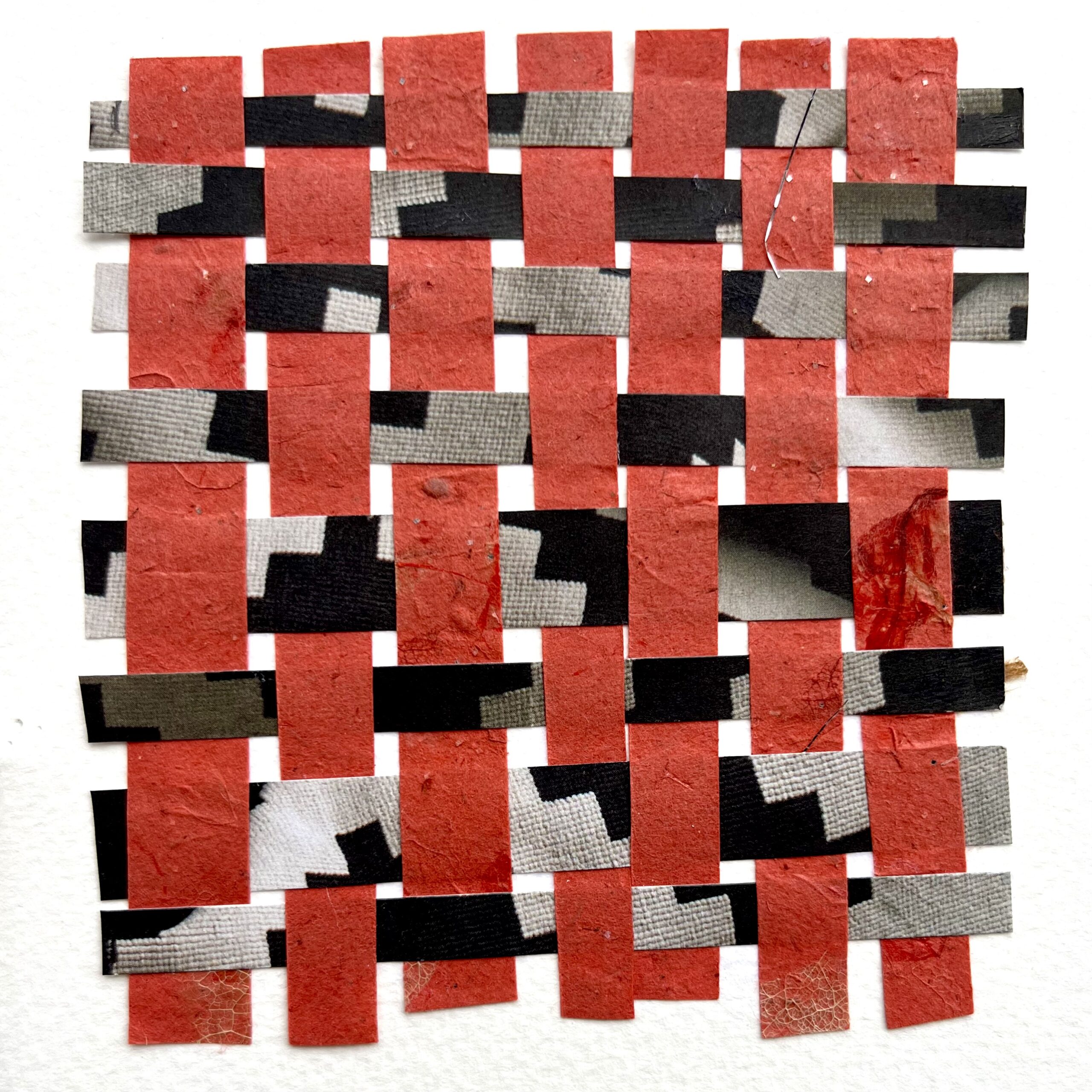

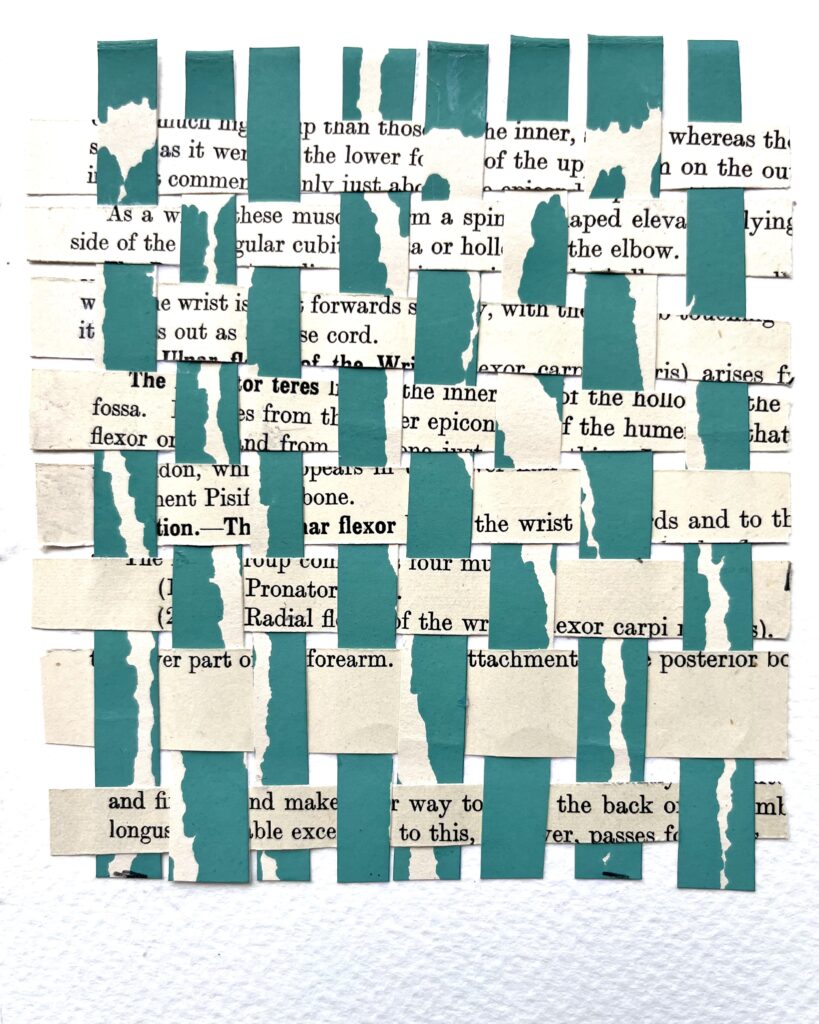

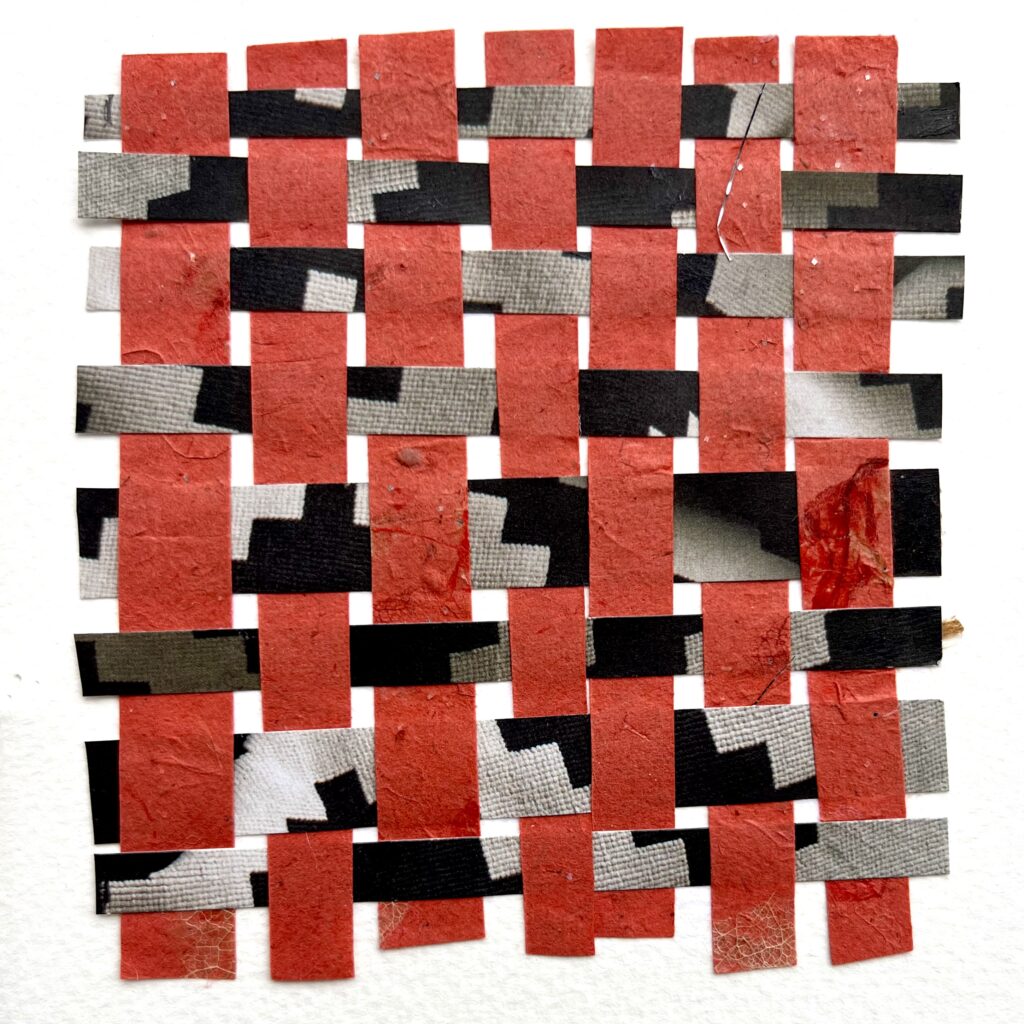

I decided to fill the pages of my third signature with simple grids woven from thin strips of paper I had hastily sliced from larger images and texts. To my surprise, these little makings—two papers quickly reassembled into a third, warp and woof—held up nicely.

Back to deconstruction. This philosophical construct, launched in the 1970s by French literary critics like Roland Barthes, Jacques Derrida, and Michel Foucault, has now made its way through academe. And constructs like “authorship,” “originality,” and “authenticity” (critiques of power) have been critically applied to every discourse one can imagine, chiefly within the humanities. Some argue that this ideational play helped an entire generation identify and listen to voices previously unnoticed. Naysayers believe this postmodern cloud of politically charged suspicion deconstructed the pleasure of reading itself.

Fifty years later, popular mention of deconstruction in Sunday sermons and social media mostly refers to the literal and figurative dismantling of things and ideas. Untethered from its philosophical and literary origins, the notion generally assumes one of two forms—a wrecking ball that indiscriminately bombasts until everything is razed or a surgical dismantling of something old or diseased that warrants renovation or repair.

During our daylong workshop, simple handiwork created space, the kind of flow and solace that is well-known to quilters and weavers.

In surprising ways, tasks like cutting, gluing, stitching, and the exercise of visual judgement opened up possibilities. Marianne knew this would happen. For many, juxtaposed visual fragments acquired meaning, pictures started telling stories. For a few, the experience was even cathartic, a sorting out of past losses or future uncertainties. From the gathered fragments we had received from Marianne, simple metaphors and small meanings emerged. Says the psalmist:

My frame was not hidden from you,

when I was being made in secret,

intricately woven in the depths of the earth. (139:13)

During boyhood I relished taking things apart. The story goes that at age six or so I entirely disassembled our toaster. Even now, I can recall the delight of turning those screws counterclockwise and unhooking springs and coils. But mind spinning and young hands gaining agility, I lacked a crucial skill: the ability to reassemble the appliance. For some time there was no toast at our breakfast table. Be careful little hands what you undo.

Our world is filled with mystery and wonder. Most every child knows this. It can also be confusing and cruel. If these realities generate a litany of questions, their presence does not confirm incoherence. In truth, the wise among us perceive the ever-emerging order of things to be coherent. There are choices to be made. One can abandon a difficult biblical text, or go back in for a deeper read. One can rightfully despair the brokenness of the world, or keep watch for signs of hope. One can lament life’s scattered pieces, or imagine a new season of reweaving.