By Cameron Anderson

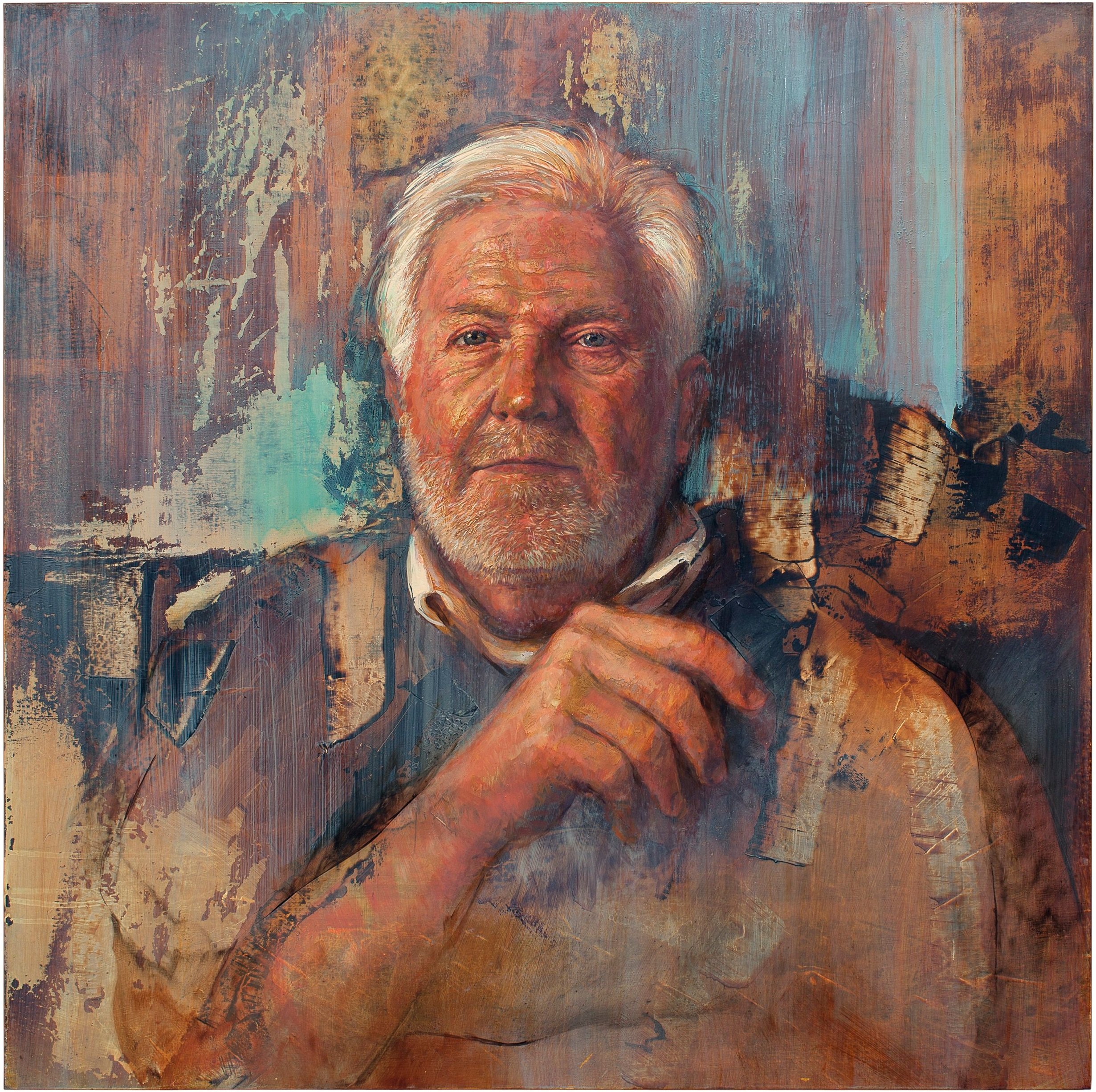

In 2009 the painter Bruce Herman’s father and mother, William and Ruth Herman, died without warning. As an act of tender remembrance he completed Painting of the Artist’s Father in 2010 and in 2011, Painting of the Artist’s Mother. Bruce explains, “Those paintings of my deceased parents opened a path for me to paint all of my loved ones and friends—and this resulted eventually in the collaborative project Ordinary Saints with the poet Malcolm Guite and composer J. A. C. Redford.” In 2013, Herman finished Portrait of the Artist: Bruce Herman and to my mind that work paired with the paintings of his mother and father anchor what has become an ambitious series: honest portraits of 25 persons with three more forthcoming.

Imagine having an artist study your face—every line, cavity, swell, and blemish—hour upon hour for many weeks. I can because, unwittingly, I became one of Herman’s subjects. But before describing what transpired, a thought or two about the disquieting experience of being a sitter, a self whose visage is being examined in such detail.

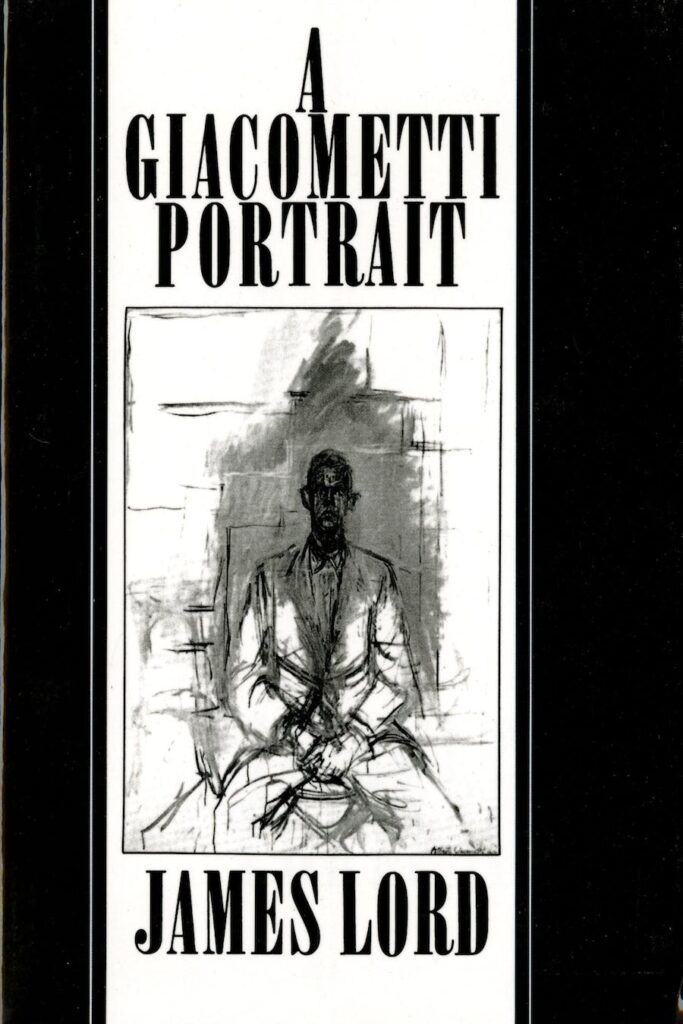

In 1964 journalist James Lord traveled from New York to sit for painter-sculptor Alberto Giacometti. Lord planned to be in Paris for a week, but Giacometti struggled to find satisfaction with the work. To accommodate the artist’s unpredictable temperament and habits, the writer canceled his return flight to New York and remained in Paris for nearly a month, drawn into Giacometti’s angst. Lord’s personal life and professional commitments were entirely upended. Recalling those days he writes:

The experience of posing for Giacometti is deeply personal. For one thing, he talks so much, not only about his work but also about himself and his personal relationships, that the model is naturally impelled to do likewise. Such talk may easily produce a sense of exceptional intimacy in the almost supernatural atmosphere of give and take that is inherent in the acts of posing and painting. The reciprocity at times seems almost unbearable.[1]

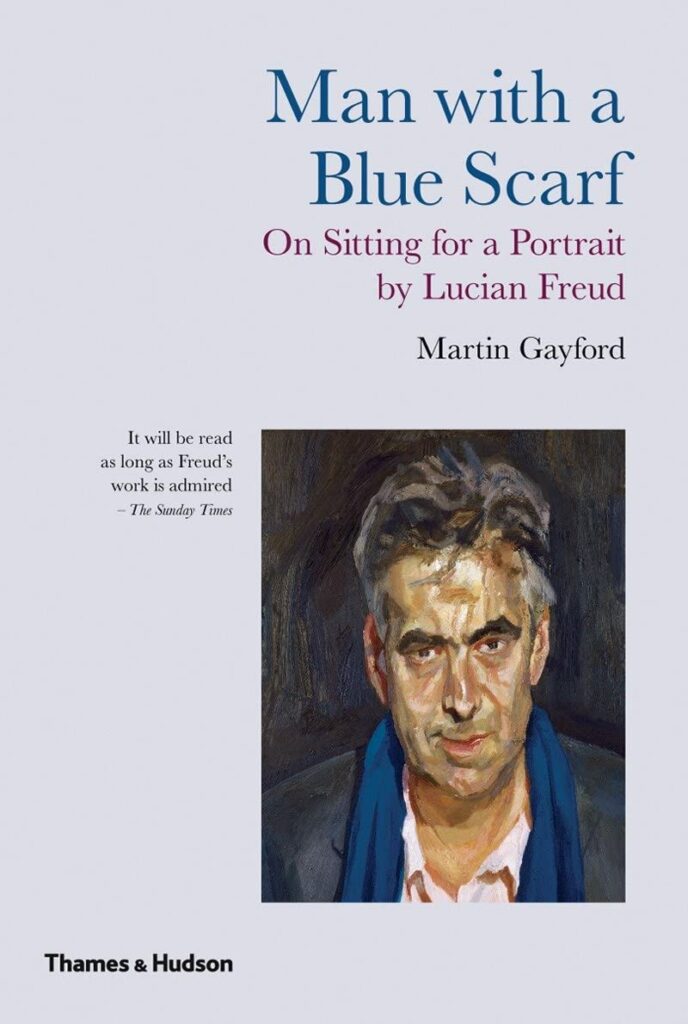

Forty-six years later, British art critic and curator Martin Gayford sat in Lucian Freud’s studio for two portraits—a painting and an etching. From November 28, 2003, onward, Gayford maintained a diary recounting the meals and conversations they shared, the critic’s own ruminations on art history, and the mental and emotional demand of being observed and painted. It took Freud (yes, Sigmund’s grandson) 18 months to complete the work.

Both Lord and Gayford penned accounts documenting the rigor and mercury of sitting for a portraitist. They are tales of model fatigue, changing light, talk about art and life between artist and sitter, shared meals and drinks, and more talk. Observes Gayford, “Sitting is a pleasure, an ordeal, and also a worry.”[2]

In October of 2018 and honoring the nine-year mark of Herman’s work on Ordinary Saints, Laity Lodge hosted an opening event. Bruce’s portraits had been installed in Laity’s Cody Center gallery, and on this evening the invited guests, including many of the portrait’s subjects, gathered to hear Malcolm Guite recite poems written in response to the portraits and listen to a small ensemble of musicians, conducted by Jac Redford, perform a musical score he had composed in response to the paintings. Portraits of Malcolm and Jac were in the exhibit. As night settled along the banks of the Frio River in the Texas Hill Country, enveloped in the hospitality of Laity Lodge, we were there together, ordinary saints gathered in paint and in person. It was a holy evening.

Here is how I became one of Bruce’s ordinary saints. In early May 2011, while staying at Bruce and Meg’s home in Gloucester, Massachusetts, one evening Bruce suggested we head downstairs to his studio. “I want to take your picture,” he announced.

Genuinely curious, I replied, “Whatever for?”

Grinning mischievously, he explained, “Oh, I’m starting a new project. I might paint your face.”

“Why?,” I wondered aloud.

“We can talk about that later. Take off your glasses,” he instructed, “and hop onto this stool.” Bruce snapped a fistful of images. Then, setting his camera aside, our conversation ranged across topics far and wide. I departed the next morning for Logan International, memories of the photo shoot already fleeting.

Seventeen months passed. Then, early one morning, I received a text message from Bruce. A text from him was not uncommon, but the attached image was. My face and right hand were emerging from a field of color applied to a gessoed panel. Through those long-forgotten photographs, I had been sitting for Bruce in absentia. Over subsequent weeks, updated images from him would find their way to my phone screen. I was becoming through the building up and tearing down of Herman’s painted surface.

Along with a later image Bruce started a text exchange that went like this, “I think I am nearly finished with your portrait, but something is missing.”

Interest piqued, I replied, “What’s that?”

“Oh, your inner conflict.”

Caught off-guard, I typed, “What conflict?”

His response, almost immediate, “The conflict between your self-doubt and your public confidence.”

In that rapid give and take, Bruce named something I had long intuitively known to be true. He stated it plainly and I took no umbrage. Even now, the insight of his gift holds fast.

Hang around Herman and you will hear frequent mention of Martin Buber’s I and Thou. True confession: I purchased a copy in college and thumbed through it more than once, but only recently have I read it in earnest. While Buber’s winding argument is a steep ascent, the Jewish philosopher’s central thesis is straightforward; the entire universe exists in relationship and our participation in it is best expressed by two word pairs, I-Thou and I-It. Buber asserts, “All actual life is encounter.”[3] I-Thou expresses our relationship with others: some sentient creatures, perhaps, but primarily human persons and divine beings. Comparatively, I-It represents our relationship with things. But an uncanny feature of Buber’s scheme is this; when an It is truly beheld, that It can become an I.

Again, Gayford: “A commonplace about portraiture is that the artist sees beyond the external appearance of the sitter, sees into their mind and—if there is such a thing—soul.”[4] It might seem that the portraitist’s task is to generate a likeness, but her greater work is to reveal essence. And so it follows then when an artist and sitter enter into the I-Thou couplet any It—a studied painting, print, photograph, or bust—that results bears witness to the encounter.

David Brooks’ newest book, How to Know a Person, is not about portraiture per se, but the candor, whimsy, and vulnerability present in I-Thou encounters animate his thinking. Says Brooks, “Wisdom isn’t knowing about physics or geography. Wisdom is knowing about people. Wisdom is the ability to see deeply into who people are and how they should move in the complex situations of life.”[5]

Again Buber, “Presence is not what is evanescent and passes but what confronts us, waiting and enduring.”[6] Since 2009, much of Herman’s studio practice has been a quest to locate wisdom and beauty in the faces of those dearest to him, and season by season more ordinary saints join those ranks. I am struck by the subtitle of Brooks’ book, “the art of seeing others deeply and being deeply seen.” I was seen by Bruce, and he also helped me to see.

Notes:

[1] James Lord, A Giacometti Portrait (1965, New York: Farrar Strauss Giroux, 1980), 37.

[2] Martin Gayford, Man with a Blue Scarf: On Sitting for a Portrait by Lucian Freud (New York: Thames & Hudson, 2013), 167.

[3] Martin Buber, I and Thou, trans. Walter Kaufmann (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1970), 62. Buber’s book was first published in 1923, and translated from German to English in 1937.

[4] Gayford, 116.

[5] David Brooks, How to Know a Person: The Art of Seeing Others Deeply and Being Deeply Seen (New York: Random House, 2024), 248.

[6] Buber, 64.