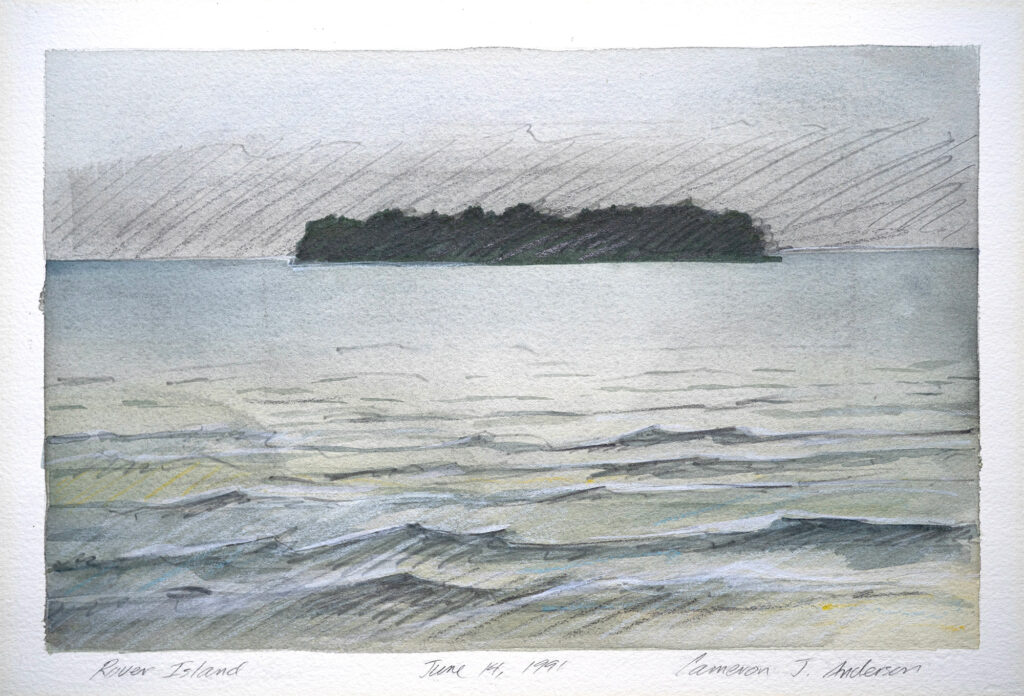

By Cameron Anderson

The watercolor sketch above is a plein-air rendering of Rover Island. I painted it on a rainy June afternoon in 1991. According to locals, Rover has never been settled. It belongs to an archipelago of 36 islands—the Les Cheneaux Islands—that string along the southward side of Michigan’s Upper Peninsula near the Canadian border. The regions’ indigenous people named these islands the “Onomonee” or “Anaminang,” that is, The Channels.[1] My composition places this small island on the outer edge of Prentiss Bay. The big water of Lake Huron, though not visible, lies beyond.

I first beheld Rover Island in 1972 while attending a week-long InterVarsity student retreat at Cedar Campus. From that summer onward, it struck me as a liminal place, though words like liminal and liminality had yet to summon my attention. In due course, those terms made appearances mostly in discussions about aesthetics and spirituality. I began to wonder, at least in the abstract, if liminal experience might be a ligament connecting the two.

These days the word liminal shows up in smart-sounding conversations as a way to account for homeless thoughts and experiences. Romantics like me might associate the liminal state with say, paddling onto a quiet lake in early morning mist. Neither notion is entirely wide of the mark, but both siphon off the more essential meaning.

Desiring to know more about the liminal state, I searched out wisdom and found two insights especially salient. The first appeared in an essay by John O’Donohue where the Irish poet reminds readers that liminality is a time or place existing between two thresholds (the Latin root for threshold being limin). A liminal space might be a physical location or a psychological or spiritual state. No matter its character, to enter it we must cross a threshold. Explains O’Donohue, “The crossing of a threshold is in effect a rite of passage.”[2] A promising business venture, the intrigue of a new relationship, a new home or homeland, or the prospect of an art commission could be fitting instances of a liminal place. Each is pregnant with potential, but what will actually transpire is unknown. O’Donohue expands the concept:

Often a threshold becomes clearly visible once you have crossed it. Crossing can often mean the total loss of all you enjoyed while on the other side; it becomes a dividing line between the past and the future. More often than not, the reason you cannot return to where you were is that you have changed; you are no longer the one who crossed over.[3]

Notice that we enter liminal space as pilgrims, not aimless wanderers. The pilgrim is on a quest to locate the second threshold and cross it. Notice also that these kinds of human dramas often get worked out in dreams, sleeping and waking. However we encounter liminal space O’Donohue’s mental model provides a useful way to account for the experience of navigating unfamiliar terrain.

Having sketched or painted Rover Island several times, and having paddled to the island, but never hiked through, I can only imagine what that traverse might require. In my mind’s eye I imagine this; I paddle out to the island, pull my canoe onto the stony beach, and set out to cross the island, reaching the other side to witness the crashing waves of Huron and to look out to the far reaches of the horizon. With Prentiss Bay to my back, I imagine entering a liminal place filled with cedar, birch, and spruce. There is no trail. I circle a granite boulder and cross a small meadow or bog. I watch the light. I listen for open water.

Nature and culture being adjacent, my imagined passage through Rover is not unlike the first time I entered Powell’s Books in Portland, Oregon, the Modern Wing at the Art Institute of Chicago, or the monumental fourteenth-century Duomo in Orvieto, Italy. Crossing the threshold of these places altered my point of view. Again, O’Donohue: “Looking back along life’s journey, you come to see how each of the central places of your life began at a decisive threshold where you left one way of being and entered another.”[4]

A second insight concerning liminality came to me while preparing lectures on the well-known story of Exodus. The People of Israel lived as captives in the Land of Egypt for 400 years when God appointed Moses as prophet to release them from their enslavement. They passed through the Red Sea to embark on what became a 40-year trek to a new land, one “flowing with milk and honey.” But that Land of Promise was nowhere in sight. In this same account, Moses’ life is laid out in three 40-year periods: first, his dwelling in Pharaoh’s court; second, his flight to Midian where, having murdered an Egyptian, he seeks refuge with Jethro, his father-in-law; and finally, leading the disgruntled Israelites through Sinai. We also learn that Moses ascended to the top of Mt. Sinai where for 40 days he met with God face to face. The compilers of Exodus deploy the number 40 with purpose.

In fact, the number 40 appears throughout the biblical narrative. A child raised in a synagogue or church will surely know the story of Noah, his family, the beasts of the field, and the birds of the air who spent 40 days and nights in the Ark to survive the Great Flood. Goliath, the Philistine champion, challenged the Israelites for 40 days before David, the shepherd boy, slew the giant with a stone from his sling. Kings Saul, David, and Solomon each ruled for 40 years. Petulant Jonah preached in Nineveh for 40 days. The pattern follows to Jesus himself who, at the beginning of his earthly ministry, was tempted by Satan in the wilderness for 40 days and who, after his resurrection from the dead and before ascending to heaven in a cloud, appeared for 40 days to his disciples and other followers in Jerusalem and Galilee.

In the biblical narrative, 40 behaves like a liminal number. In each of these stories the protagonists enter a place of consequential struggle, sometimes for life itself. The poignancy of this metaphor is amplified in personal and communal terms. In ancient Israel, 40 years was thought to be the span of a normal life. The People of Israel occupied the place between liberation and promise for 40 years.

We spend much of life preparing, risking, longing, and waiting. We choose stasis, but encounter flux. According to Catholic theologian Josef Pieper, “the status viatoris is, then, the ‘condition or state of being on the way,’” a state in which we remain until death.[5] Could it be that the wilderness sojourn is a picture of normal life? What conditions will we face on the journey? When, if ever, will we reach our destination? These questions will be answered, but we must first enter the journey. The metaphor only gains gravitas when one crosses the first threshold.

For artists, the studio, the practice room, and the writing desk are sites of toil and reward. They are liminal spaces. Artists enter each project understanding, at least intuitively, that failure is possible. And when failure greets us (it will), we must gather up our receipts of time, money, and missed opportunity, pause to lament, and start again. The arrangement feels untenable, even maddening, until you realize that creative work occurs in flux, until you grasp that liminality is the crucible of the beautiful.

Space between lies at the heart of art practice and religious devotion. There we encounter the traverse from womb to tomb, the gap between God and humankind, the distance between creative action and beauty. Practitioners—those who make, sacrifice, and pray—occupy this space and in lucid moments we understand that to be alive is to be on the way.

Notes:

[1] Frank R. Grover, A Brief History of Les Cheneaux Islands (Evanston, IL: Bowman, 1911), 14.

[2] John O’Donohue, “To Retrieve the Lost Art of Blessing,” To Bless the Space Between Us: A Book of Blessings (New York: Doubleday, 2008), 194. Admittedly, O’Donohue’s treatment of this concept is a popularization. Many credit Dutch-German-French ethnographer Arnold van Gennep as the one who first introduced this idea to the social sciences with the publication of his book, The Rites of Passage (1909, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1961). In it van Gennep outlines three stages of development: “separation, transition, and reincorporation—or, respectively, preliminal, liminal, and postliminal.” https://www.britannica.com/topic/rite-of-passage

[3] O’Donohue, 192-193.

[4] O’Donohue, 192.

[5] Josef Pieper, On Hope (Ignatius Press, 1977), 11-12. I thank Bobby Gross for this reference.