By Cameron Anderson

Our father was failing. So we, his six children with three spouses, quickly gathered at Congregational Home. It was a Sunday morning. Arriving in ones and twos, we signed in at the registration desk of his assisted living facility and made our way down the familiar hallway to Dad’s room. He was asleep; peaceful it seemed, but breathing weak and slow. He never woke to greet us. At age 89, the life of a truly good man expired and we were present.

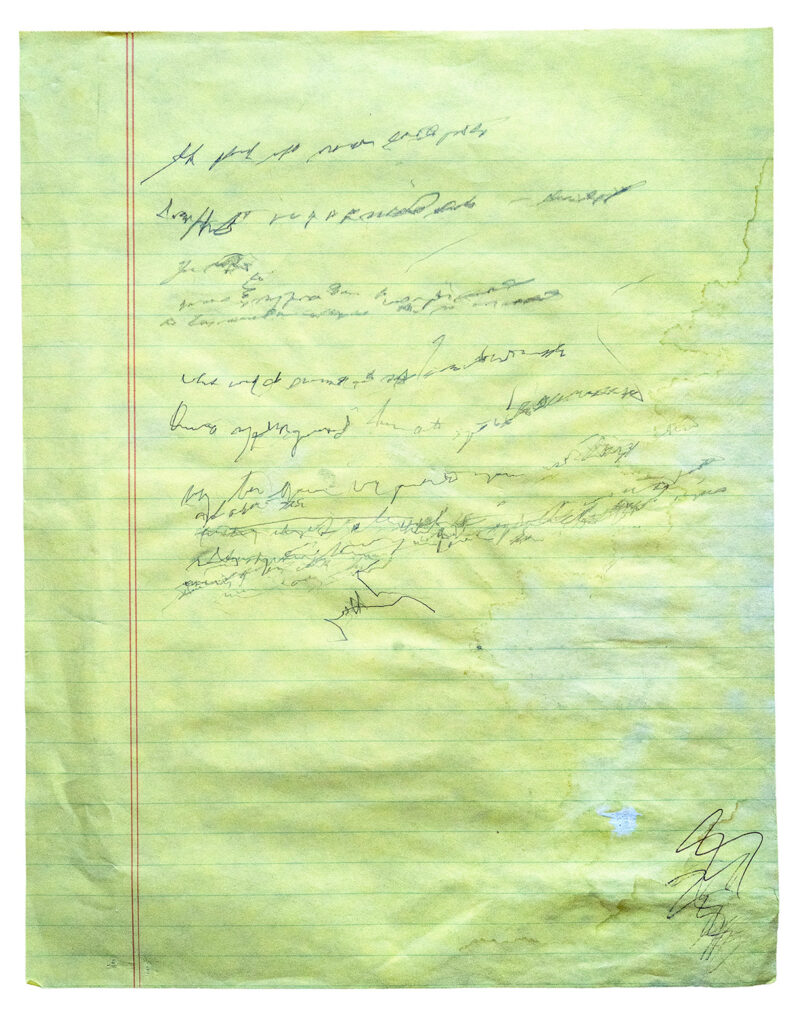

Sad in heart that mid-November day, we said farewell to our father and then to each other. Preparing to leave the room, I spotted a yellow legal pad on the nightstand. The tattered tablet half-filled with writing in pencil caught my attention. For as long as I can remember Dad kept one nearby. Early in the morning, coffee in hand, he prepared lessons, drafted meeting agendas, and while reading took notes on those blue-lined pages. I slipped it into my leather satchel.

A day or so later I pulled the pad from my bag eager to discover what my father had written. It was reasonable, I thought, to suppose his final words were memorialized on the yellow tablet. I hoped to read them but that desire was thwarted. Every line of Dad’s cursive scrawl was illegible.

A new sadness washed over me. What, I wondered, were the last thoughts of this thoughtful man? Prayers? He was devout. Perhaps memories of Carney, the small rural community in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula where he grew up? In his final months that home place seemed entirely real to him, as if he were there with older brothers Wes and Gil, two of eight siblings all of whom preceded him in death. But this patch of unreadable script might have been a list of worries, nothing more.

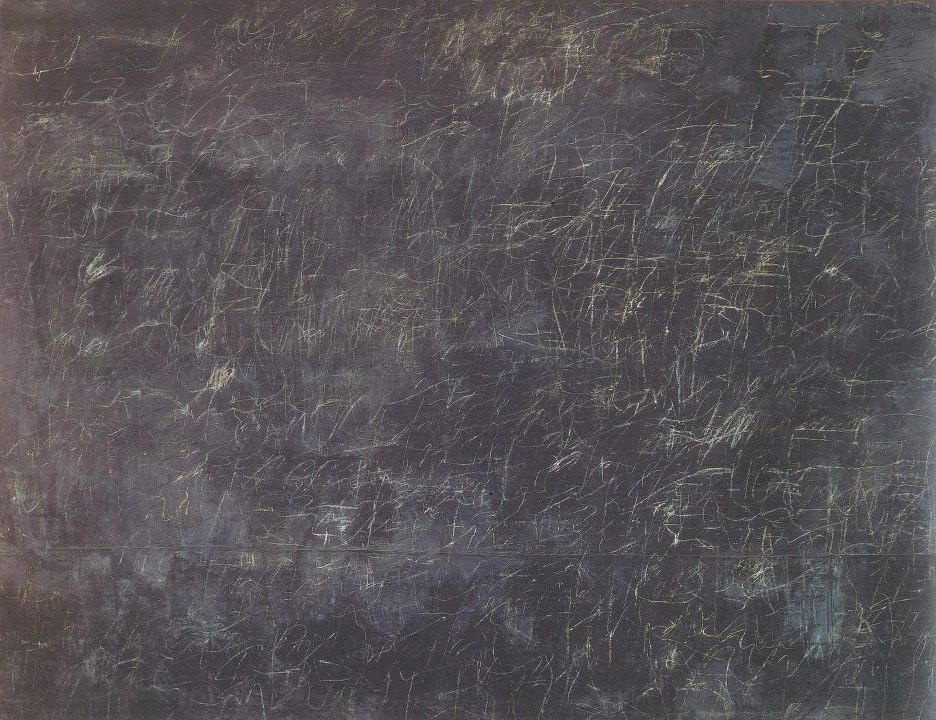

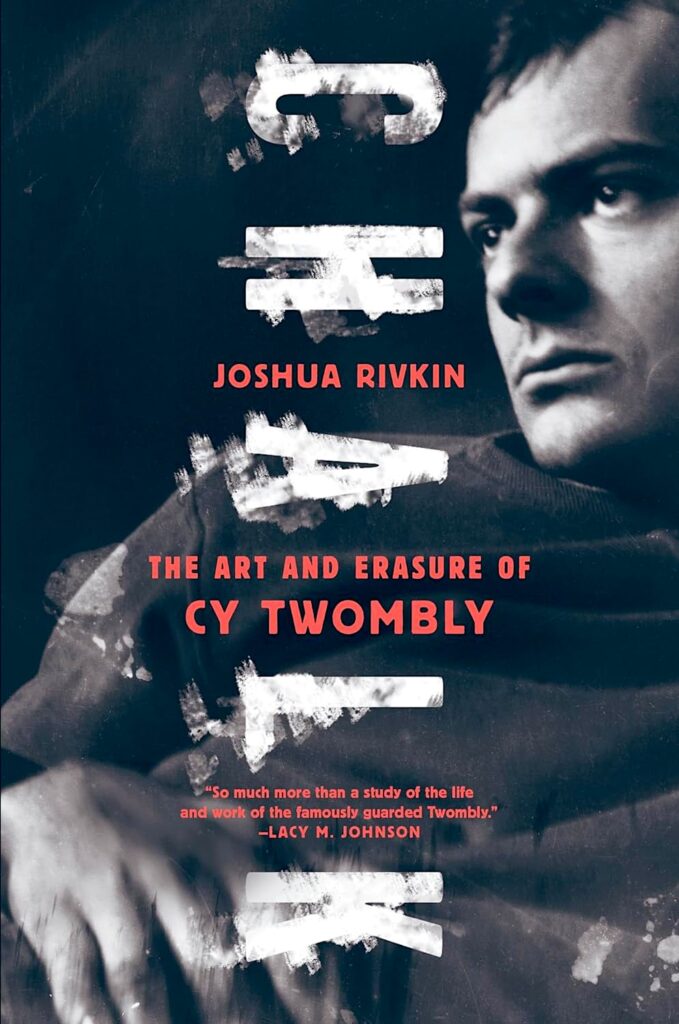

Studying my father’s illegible lines brought an early painting of Cy Twombly to mind, Panorama (the work displayed at the top of this essay). In his poetic book Chalk: The Art and Erasure of Cy Twombly, Joshua Rivkin writes: “Panorama, most likely completed in 1954, is all the more noteworthy for being one of six similar large-scale paintings done in [Robert] Rauschenberg’s Fulton Street studio, and the only one not destroyed.”[1] Like so many Twombly pieces this is a large canvas, measuring 100 x 134 inches. The artist used oil-based house paint, wax crayon, and chalk on canvas to make the work and it anticipates a later body of chalkboard paintings produced by Twombly in the ‘60s.

In the 1950s my father, a high school history and economics teacher, would have been well-familiar with classroom chalkboards; the soft white or yellow gypsum stroked against hard, dark gray slate. By the end of each school day marks and erasures filled those boards and in those days a night custodian using water and a rag would dutifully wipe them clean. Word constructions, math equations, world maps, and diagrams, learning’s ebb and flow washed away.

I suspect it is the speculative character of Twombly’s scrawling text and ciphers that draws me to his work. It might also be the temerity of his nonchalant gestures as he works out premonitions and recounts histories on the picture plane. “To collapse the very definition between a drawing and a poem, to ask if the boundary between them is more fluid, more uncertain, than we often think—this is Twombly’s ambition,” writes Rivkin.[2] Twombly’s body of work is no embrace of conventional ideas about beauty.

Born in Virginia, Cy Twombly studied at the Art Students League in New York during the heyday of abstract expressionism and later Black Mountain College in North Carolina. He began exhibiting work in New York but eventually relocated to Italy where he met and married Baroness Luisa Tatiana Franchetti. Cy and Luisa maintained a permanent home and studios in Rome, where they fraternized with artists and aristocrats. The artist also made regular trips to the U.S. to exhibit work. Twombly was avid reader, drawn to Greek history and mythology as well as modern texts. He was also athletic, some say elegant, and enigmatic to the extreme. “There is always mystery, concealment, at the heart of Twombly’s work and life.”[3]

To be clear, no part of my father’s rural world and Twombly’s far-flung cosmopolitan life ever touched, despite having lived at the same time except that now they do for when I noticed Dad’s late writing, I thought immediately of the inchoate and fleeting work of Twombly’s hand and mind. Comparing my father’s illegible pages (a treasure to me) to Twombly’s Panorama (an artworld treasure) prompts a thought or two about language. In some academic quarters the limits of language, its inability to plumb the depths of human experience or to offer a cogent account of our being in the world is extolled. For nearly a half-century the fashionable focus of literary criticism has been to deconstruct language, to highlight its fault lines and elisions. This effort underscores language’s lack but also notes its power. Theorists and activists alike are keen to engage in discourse on the latter – in this irony always lurks, not least in the striking use of language to outline language’s limits. The serpent, it seems, slithers quickly to grab hold of its own tail.

There should be easy agreement that written and spoken language is delimited, that there is territory beyond its reach: the ineffable and the imponderable, life’s great mysteries and deep sorrows. That said, is not the greater truth that written language is among humankind’s most remarkable achievements? Its fulsome capacity, fluidity, elasticity, and intelligibility endures and inspires.

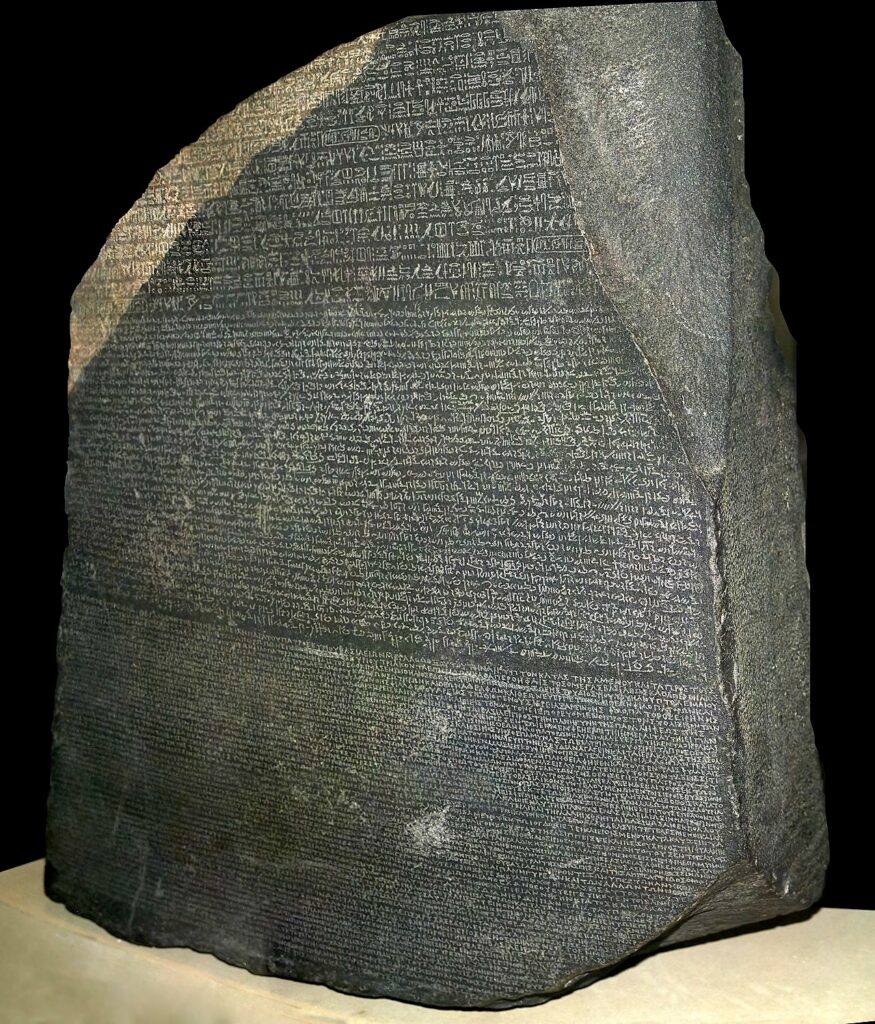

Anthropologists estimate that purposeful human mark making first appeared around 40,000 B.C.E., if not much earlier. Cave paintings lined out on rock walls and ceilings in softer clay bodies and charcoal. Petroglyphs, carvings and incisions made directly in stone. Ancient minds and hands generated symbols, letters, and alphabets. Writing evolved as a gesture and stroke. Hieroglyphs emerged in Egypt around 5,000 B.C.E. The famous Rosetta Stone (pictured below) boasts three inscriptions of the same decree issued in 196 B.C.E by King Ptolemy V Epiphanes: in ancient Egyptian using hieroglyphic and Demotic scripts and ancient Greek. It would be a pleasure, I think, to see the Rosetta Stone and Panorama on display in the same gallery.

In 1991 George Steiner made a bold claim: “[A]ny coherent understanding of what language is and how language performs . . . any coherent account of the capacity of human speech to communicate meaning and feeling is, in the final analysis, underwritten by the assumption of God’s presence.”[5] The biblical creation narrative, echoed profoundly in the prologue to John’s Gospel, sets the stage for Steiner’s claim: God speaks and makes a world. The power of that speech act—a Big Bang, perhaps—is beyond comprehension. Grace Hamman observes, in her fine little book, Jesus Through Medieval Eyes, “We are left with words crumbling in our mouths as the Word Incarnate, perfect marriage of form and content, leads us toward the ineffable, unspeakable face of God.”[6]

In early morning hours, coffee in hand and a yellow legal pad nearby, I remember my father with fondness. I marvel at the wonders of art and language. Remarkably, incomprehensibly, God’s image bearers also speak and write. And like Hamman, I believe there is a world beyond this world, that in some time above or beyond we will meet God face-to-face. What, I wonder, were my father’s first words in that new time and place? I trust that, having received a resurrection body, his hands are now steady and his voice strong.

Notes:

[1] Joshua Rivkin, Chalk: The Art and Erasure of Cy Twombly (New York: Melville House, 2018), 27.

[2] Rivkin, 80.

[3] Rivkin, 76.

[4] For more on deconstruction, see my blog Thickly Woven.

[5] George Steiner, Real Presence (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1991), 1. Steiner’s treatise challenged deconstruction. He claimed that meaning and coherence was impossible apart from theological or religious belief.

[6] Grace Hamman, Jesus Through Medieval Eyes (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2023), 109.

Photo Credits: Yellow Legal Pad, Scott Wilson, Rosetta Stone, Creative Commons © Hans Hillewaert.