A Story

“How do you like my collection?” Unsolicited, the man’s question is a bemused accusation. Stopping to grab morning coffee, I had parked next to a tired Malibu and he’d seen me peering through its windows. It was hard not to look. Save for a small clearing on the driver’s side, the faded blue Chevy was piled near to the ceiling with yellowed newspapers, unopened mail, shoes, shirts, and plastic containers. We both knew I’d made a judgment. The four-door sedan was his.

Heading toward the counter but a step or two before passing the man, he lightened the moment, “Nice morning, huh?” It was. June sunshine was burning off the early damp air and the cafe’s garage-style doors were open wide.

Our neighborhood cafe—a retrofitted butcher shop—is a morning way station for commuters heading to UW-Madison, the State Capitol, and downtown law and tech firms. “A medium latte with almond milk to go,” explains one customer. Another, a thirty-something, denim jeans cuffed and a pencil tucked behind his ear, barks into his mobile and pushes through the door, “Well yeah, but no, not really, I mean . . . you just need to deal.”

The espresso machine hisses. Baristas slip scones, blueberry and oat, into paper bags and moms enter with kids in tow. A four-year-old being hurried off to day care eyes a sugar cookie and a box of juice. “Good morning, Jordan,” says another parent to the counter help. “Get me a chocolate croissant and some green tea, hot.” Then looking back toward her two boys, “What do you guys want?” The mention of food wrests them from sullenness.

Minutes later a posse of Edgewood High School students drop their backpacks on a table and shuffle five chairs in close. My coffee now in hand, I settle into the worn upholstered chair next to my interlocutor. I take my first sip and he offers, “Yeah, my name’s Charley, Charles, really. But I am not a Chuck, no sirree, don’t call me Chuck.” Trailing off, “Yeah, just call me Charley.”

Mid-seventies, perhaps older, his bright gray eyes peer from behind a pair of dated wire rims, but his unbuttoned faded flannel shirt and hi-top black and white sneakers suggest attitude. There’s more—Charley has started his day not with tea or coffee but an IPA. Before COVID the cafe kept two or three seasonal brews on tap. He places his morning pint on the small metal table next to him and nurses it along. Around 7:45 he starts a second.

Like a character in a John Cheever short story, Charley has inverted the acceptable order: caffeine to launch the day, alcohol to wind it down. Unsolicited, I fashion a little purgatory, a forlorn place for hoarders and alcoholics, and make a place for him. My second judgment.

On a typical day the regulars begin to file in at 6:30, as the shop opens. Boyd, a local real estate developer, is often first. He sits for 30 minutes or less on the left side of the front window greeting those he knows and checking his cell. Will, always in a freshly pressed, button-down white Oxford, gets his to go, but perches on a stool facing the side street and spreads out his Wall Street Journal. And these days Charley has his spot, the left side of the gas fireplace. Not infrequently, on mornings when I stop in, he, like a rooster sticking his curious head from a cage, bids me good morning.

Charley’s pint is not all that occupies the blue-topped table next to him. He uses it to display a curious menagerie of things—twigs, stones, feathers, and keepsakes. I watch as Charley’s blue-veined forefinger nudges a porcelain dog toward a dark polished stone. Then he reaches for a spiral bound notebook and scribbles a sentence or two. Pausing, he directs his eyes up and to the right. Returning from that thought, he scoops up the miniature Dalmatian, stows it in his breast pocket, and takes another a sip from his pint. Then unfolds a newspaper, thumbs through it, and jots another line in his tattered notebook.

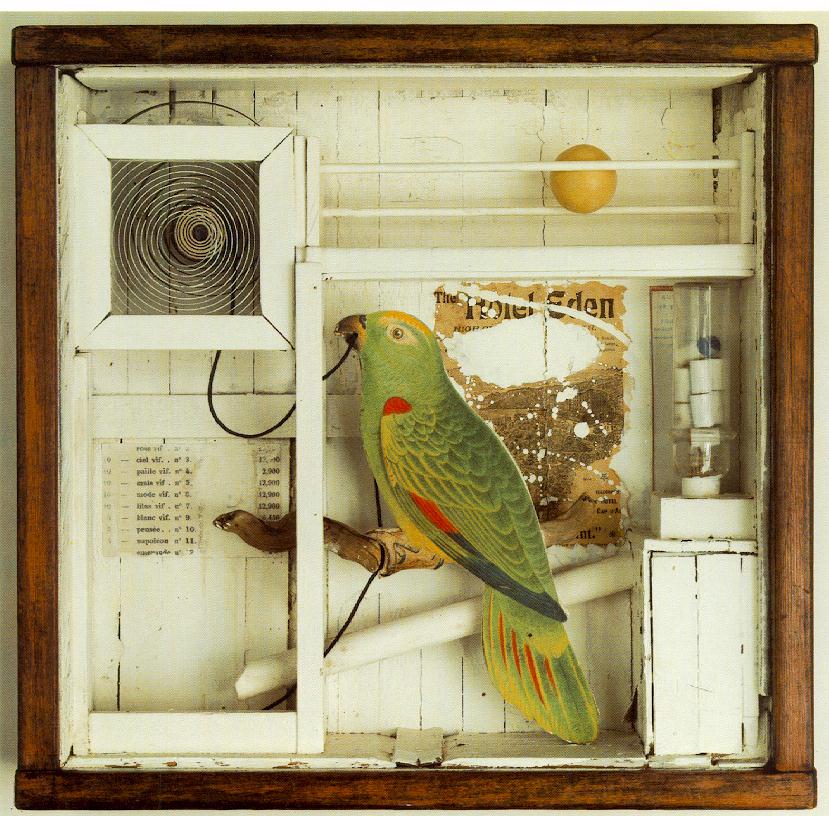

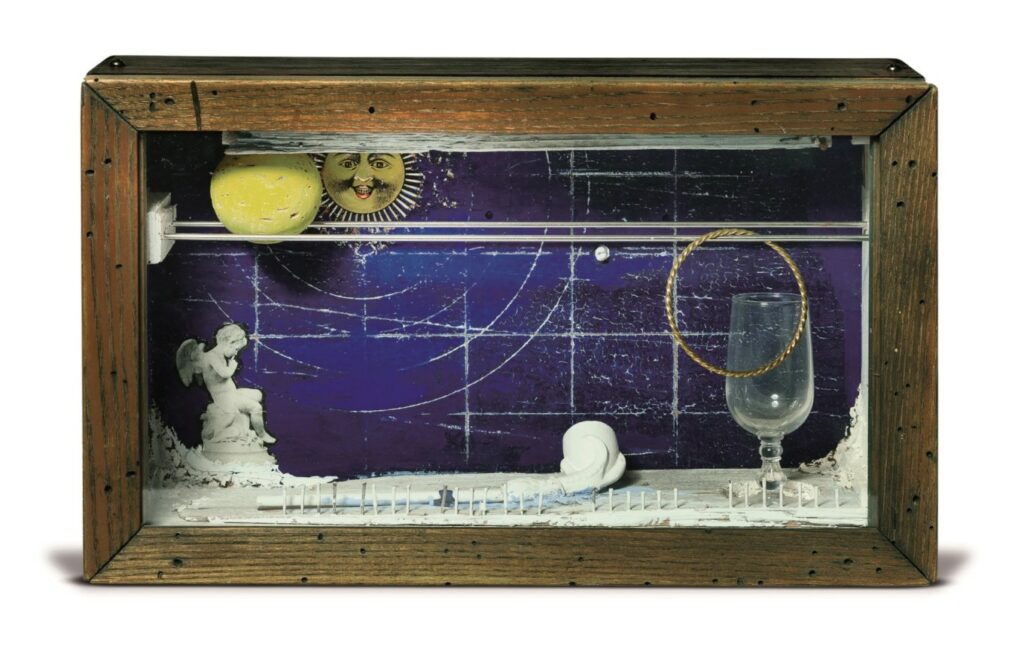

Charley rotates his collection. One morning there may be a dogwood twig, red and smooth, placed near to a robin’s egg. The next, a carved animal, fossilized something, and glass marble appear. I wonder, but don’t ask, if he knows of Joseph Cornell, the assemblage artist who gathered up objects he thought interesting and beautiful—Victorian bric-a-brac, dime-store trinkets, old photographs and magazine cutouts—gleaned from secondhand shops in New York. He arranged these to fashion glass-fronted boxes and dioramas—an artist’s wager, really, imagining that cast off curiosities could be assembled to form new meanings.

Joseph Cornell, Untitled (The Hotel Eden), 1945

During his teen years, Joseph attended the prestigious Phillips Academy in Andover, Massachusetts. But following the early death of his father, his schooling ended. From age 26 onward the artist lived with a demanding mother and his younger brother, who suffered from cerebral palsy, in their home at 3708 Utopia Parkway in Flushing, Queens. There he maintained a basement studio. For a decade or so, he worked in Manhattan as a textile salesman. His was a hard life and he battled long seasons of depression.

Though untrained, Cornell is regarded as one of the most important American artists in the modern period. In the 1930s and ‘40s he was often associated with the Surrealists and throughout his career he maintained connections, often through correspondence, with artworld luminaries like Salvador Dalí, Marcel Duchamp, Willem de Kooning, and Mark Rothko. In one letter, Rothko praised the “uncanny magic” of Cornell’s work. His fame notwithstanding, the assemblage artist and filmmaker spent most of his life as a recluse.[1]

Joseph Cornell, Untitled (Solar Soap Bubble Set Series), 1955

Now my thoughts drift. I recall the exotic things Uncle Gil and Aunt Grace brought home from Ethiopia while on missionary furlough during the 1960s and ‘70s, brightly colored stuffed songbirds, butterflies behind glass, hand-carved wooden gazelles, giraffes, and zebras.

I too am fascinated by objects. I’ve filled several cigar boxes with personal treasures. A half-dozen plastic tubs in my basement vouchsafe found or half-made things that, I wager, may someday appear in new work. I also have plans for the handsome planks of maple, oak, and walnut stacked so neatly in my garage studio. Last year I carefully sorted my dappled things—dozens of jars and bins of nails, screws, and other hardware.

“Thou hypocrite,” charges the Son of Man, using his best English. “First cast out the beam out of thine own eye; and then thou shalt see clearly to cast out the mote out of thy brother’s eye.” (Mt 7:5, KJV)

This morning I am sipping French Roast. Charley nurses his pint and pecks at a scone. What, I wonder, should I make of his small enchantments and odd habits? No doubt a well-placed question would unlock a secret or two. But, I reason, this is all wrongheaded. His answers are no business of mine. Rather, in this morning hour before the world opens wide, I am bound to Charley, Cornell too, so also an unnamed Ethiopian woodcarver, by a shared understanding: objects, found and made, are signs and wonders to guide us through our journey of days.

Notes:

[1] In 2023, collectors Robert and Aimee Lehrman made an historic donation to the National Gallery in Washington D.C.: twenty of Cornell’s box constructions and seven collages. National Gallery of Art Receives Major Gift of Works by Joseph Cornell

My thanks to friend and science fiction writer Susi Jensen for helping me through at least four drafts of this story, a new form for me. Thanks also to Scott Wilson for his photos of “Charley’s menagerie.”