By Cameron Anderson

Plant gardens, eat what they produce.

—From a letter to the exiles in Babylon, Jeremiah 29:5

The opening chapters of Genesis attempt nothing less than to describe the beginnings of the whole created order. But within this grand theological narrative we also gain insight into the blessing and burden of work. Genesis 1:1-2:4 and 2:5-25 features two accounts of creation. They tell us that the first man and woman were fashioned by God to bear his image and that they were given work to do. Genesis 3 goes on to describe Adam and Eve’s disobedience and the subsequent curse that fell on the serpent, their tempter, and them. If chapters 1 and 2 describe the blessing of Adam and Eve’s God-given responsibility to exercise dominion, be fruitful and multiply, name the animals, and tend the garden (these often termed the “cultural mandate”), then chapter 3 describes the burden of lives lived east of Eden.

Attentive readers may notice that the first creation account possesses a linear cadence; God speaks, creates, and then blesses. By contrast, the second does not follow this rhythmic pattern, nor does it repeat the ordering of the six-day creation. The first account describes the creation of vegetation on the third day and the creation of humankind on the sixth. Following that, God promises the man and woman that “every plant yielding seed that is upon the face of the earth, and every tree with seed in its fruit, you shall have them for food.” (1:29) The second account offers an alternate sequence. Genesis 2:5 tells us that “no plant of the field was yet in the earth and no herb of the field had yet sprung up—for the LORD God had not caused it to rain upon the earth, and there was no one to till the ground.” Had God withheld the completion of his verdant garden until the human was available to till it? This is what the second account proposes. Reading on in Genesis 2, we happen on the second telling of humankind’s creation:

Then the LORD God formed man from the dust of the ground, and breathed into his nostrils the breath of life; and the man became a living being. And the Lord God planted a garden in Eden, in the east; and there he put the man whom he had formed (2:7-8).

Having “formed the man” and “planted the garden,” God “put the man whom he had formed” there. In doing so, the Creator’s desire for someone to “till the ground” (2:5) is perfectly met. Genesis 2:9 goes on to tell us that “out of the ground the LORD God made to grow every tree that is pleasant to the sight and good for food . . .” Then Genesis 2:15 recaps the entire sequence, “The LORD God took the man and put him in the garden of Eden to till it and keep it.”

The import of this ancient creation story is not lost on our modern situation. The agency that God lavishes on his first image bearers is the means by which they will both enjoy the Creator’s generous provision and discover his purpose for their being in the world. This picture of reciprocity between God and humankind depicts something more than responsibility, something more than the provision of God’s blessing paired with the obligation his creatures have to do his bidding. It plumbs greater depths, it depicts fidelity.

Professor Cal DeWitt, mentioned in last week’s blog, points to the critical placement of the word “till” (as translated in the New Revised Standard Version) in the second creation account. “Till” is first mentioned in Genesis 2:5 and then again in 2:15, where it is paired with the word “keep.” The New International Version translation offers “work it” and then “take care of it.” But I find John Goldingay’s translation more in keeping with the narrative. He translates “till” in 2:5 as “to serve the ground,” and “till” and “keep” in 2:15 as “to serve it and keep it.” [1]

While the two creation accounts differ in detail, their rationale is aligned. The first account seeks to establish God as Creator and to outline the ordered nature of the cosmos. Meanwhile, the emphasis of the second is to describe the nature of humankind and their relationship to the Creator and all that he has made. Both accounts tell of God’s generous provision—the greens and grains, nuts and fruit that will sustain the man and woman. The second confirms something more—God charges the humans to be stewards of the very garden that will nourish them.

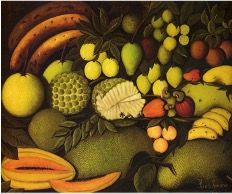

This biblical image of abundance brings to mind Henri Rousseau’s (1844-1910) Still Life with Exotic Fruit. Living in Paris, Rousseau sought the affirmation of post-impressionists like Paul Gaugin, Camille Pissarro, and Edgar Degas. But for most of his career, he remained an impoverished outsider. Only late in life did he receive some critical attention, but even then the work of this untrained artist was thought to be primitive or naïve. Eden-like tropical plants and wild animals made frequent appearance in his oeuvre and, on occasion, depictions of Adam and Eve. Though Rousseau was hardly a student of the human form, I think that the brightly-colored, succulent fruit depicted in this late, lesser known, work wonderfully showcase the superabundance of Eden. [2]

The human (adam) is to serve the earth of the ground (adamah), the very ground from which he was fashioned and the same ground that will sustain the plants, herbs, and trees that provide him with food “that is upon the face of all the earth.” The dwelling place that God has provided the man and the woman is Eden’s garden. This place will require their attention, but we should not imagine that, in their prelapsarian state, the humans are God’s conscripted labor. Rather, they are invited to co-labor with him so that every facet of their work will bear ongoing witness to God’s goodness. In the most literal sense, their vocation is situated within and building up the ecology of paradise.

The pathos of Genesis 3—Adam and Eve’s disobedience—entirely disrupts the fidelity described in Genesis 1 and 2. As mentioned, the serpent, the woman, and the man are destined to live beneath God’s curse. But notice that even amid all of this tragedy and alienation, the cultural mandate is never rescinded. In mercy, Adam and Eve’s efforts still count for something. Though frustrating, their daily work will be evidence of their continued agency in the world and, at least in part, at the core of their purpose.

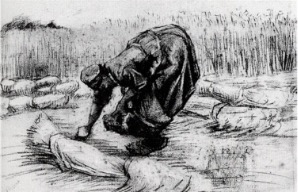

Vincent van Gogh (1853-1890) rendered this drawing, Peasant Woman, Stooping Between Sheaves of Grain, five years before his untimely death. It depicts the dark image of a solitary woman and the great bend of her back as her right hand reaches low to gather a bit of grain. Her face is hidden in shadow and her labor is the kind that causes young bodies to grow old. In effect, van Gogh’s solitary labor as an artist confirms the woman’s humanity as a fieldhand. In his early twenties, van Gogh was an itinerant Christian evangelist serving miners and their families in Borinage, Belgium. Having suffered greatly, he understood the woes of the peasant class.

The extent of humankind’s dominion is broad. Godlike, we possess the capacity to direct and consume the life of world. In fact, we are permitted to usurp Creation’s self-regulating ecology by exploiting and eliminating species of plants, fish, reptiles, birds, and animals and toxifying its land, water, and air. Our distressed global environment is prima facie evidence that we have defaulted on our obligation to tend God’s garden. When dominion is exercised as domination, humankind ceases to serve the ground.

Yes, east of Eden, Adam and Eve’s work is a great labor—the torturous labor of birth for the woman and the grinding labor of tilling for the man. Their living will be wracked with angst and sorrow. And yet hope is never entirely absent. Even beneath the curse, the humans would—as do we—enjoy life, learn to love, celebrate, and worship. God’s mercies prevail until his kingdom comes, first as the glimmer of messianic light on history’s horizon, and soon in fullness.

Notes:

[1] John Goldingay, The First Testament: A New Translation (InterVarsity Press, 2018).

[2] Roger Shattuck, “Object Lessons for Modern Art,” in Henri Rousseau (Museum of Modern Art, 1986), 11-22.