A Letter to My Sister-in-Law*

Dear Dawn,

Detritus, the word, has attitude, and I am confident you introduced the term to me. The way I remember it is you spending a week or so at your cozy Northwoods cabin on Petticoat Lake. Looking about, you spot something out of place. Detritus. Beaming a welcoming smile, you approach. “Hi. Have we met?” That smile now fading, “Hmm, you don’t belong here, do you?” One of two outcomes is certain: the item in question will be returned to its proper place—a drawer, basket, or closet—or swept away.

Recently, I learned about asàrotos òikos (unswept floor) mosaics. Pictured above is a detail from one that decorated the floor of a villa dining room on the Aventine Hill in Rome that I think will amuse you. It was discovered in 1833 and is now on view in the Gregoriano Profano Museum in the Vatican. Works like these have been discovered in the domiciles of other Roman elites. Mosaics first appeared in late fifth century B.C.E. Greece. To create them, artisans painstakingly produced tesserae—tiles or cubes of colored stone, marble, ceramic, and glass—which they assembled in puzzle-like fashion to form patterns and scenes. This asàrotos òikos is a second century B.C.E. work completed during the reign of Emperor Hadrian. With unusual whimsy and skill, Heraklitos, the artist, enshrined the remains of a feast strewn about the villa’s dining room floor. Daniel Colin offers this inventory:

You can clearly see remains of leafy vegetables (perhaps endive and artichoke leaves?), fruit (grapes and what appear to be cherries), lobster and crab claws, a fish head and skeleton, clams, oysters, and various other mollusk shells, sea urchins, snail shells, chicken feet, bones, and nut shells. The artist even added a little mouse who has snuck into the dining room and is quietly gnawing on a walnut shell.[1]

Finely rendered and radiating charm, this asàrotos òikos also embodies excess and decadence. Imagine the conversation between household slaves tasked to clean up the mess as they sweep away the evening’s debris from the artfully depicted detritus beneath? And, Dawn, I realize that cabin owners like you may not find the little mouse so endearing.

While detritus can be scatological, when you call out a bit of birch bark or a dark-hued moth (and maybe a couple of mouse droppings) on your cabin floor, I believe you bestow dignity (albeit brief) to castaways. An unshelved, faded green Modern Library book, a black Sharpie, the ceramic mug abandoned after morning coffee—wastrels requiring your attention. But surely you will preserve for a while the pinecones your young grandson, Basil, gathers while hiking with you. And speaking for my brother, Gar, and myself, in the pleasant world of ordered things, please grant another day to any Dave Brubeck CD you find lying about.

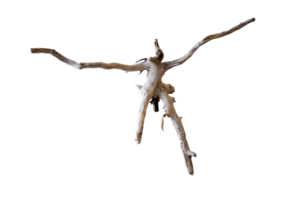

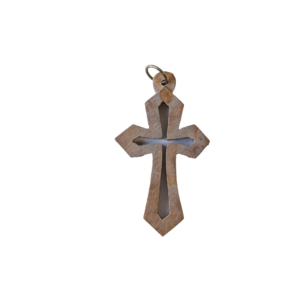

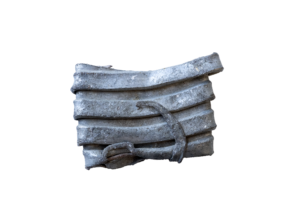

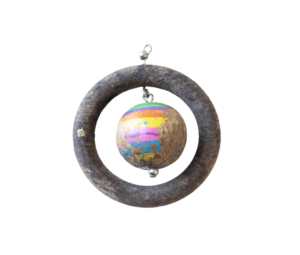

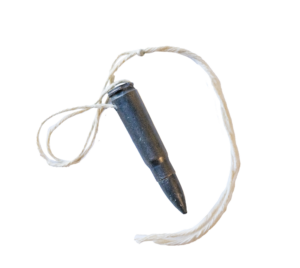

By now you realize I am writing to defend detritus, that species in the genus of unremarkable things. Indeed, I have stowed such a congregation in the upper right drawer of an inherited chest of drawers in my bedroom. Years pass and this collection of small things rests mostly undisturbed. It contains a handful of foreign coins, two retired pairs of eyeglasses, a pocketknife dull beyond use, my high school diploma (but no others), and several bottle openers, one in a brown leather sheath. Also a few anniversary cards from C.K. and a pair of black shoelaces. A pulpboard coaster from Cuchi Cuchi memorializes the night two friends pledged, with some delight, 25K to a project I was working on. All these temporary keepsakes and no treasure, save perhaps a polished black onyx egg given to me in my middle teens by a young woman with whom I was smitten.

The one tasked to sort this cherrywood drawer after I depart will likely keep the black egg, but the memory it summons will slip away. Alas. Cabinetmaker Peter Korn is right to observe, “Once it enters the world, an object gathers history and associations on its own.”[2] How can one object be so freighted with meaning—55 years have passed—and not another? The remains of that drawer? Detritus.

Photographs of my detritus by Scott Wilson

Dawn, you may know that I am a fan of Yale poet, Christian Wiman. In his latest book, Zero at the Bone: Fifty Entries Against Despair, he writes, “One grows so tired, in American public life, of the certitudes and platitudes, the megaphone mouths and stadium praise, the influencers and effluencers and the tsunami of slop that comes pouring into our lives like toxic sludge.”[3] Echoing Wiman, I am desperately concerned about our present cultural condition. Anxiety and loneliness have crested to epic levels. Somehow, we have wandered into a world unsuited for human life. Have you noticed the spectacle? Grandiosity piled atop grandiosity. Bombast provoking bombast. Desire stirring desire. It’s a kind of cultural hyperthyroidism and the decibels of its mostly hollow promise increase with each new post and performance. By design, we are becoming precisely what we consume.

In some instances, detritus poses an existential threat. There is now an island of plastic microparticles, jetsam in the Pacific Ocean. It is known as the Great Pacific Garbage Patch (GPGP) and is twice the size of Texas. Horror enough that this exists, is it not also a metaphor for the vitriol and rage that pools about us?

Meta. Mega. Maga.

I propose a more virtuous “M” word. Mere.

The world I long to live in is a merely good, merely kind place, well-suited to mere humans. In the shadow of mighty Rome, a Jewish teacher from backwater Galilee instructed those with ears to listen. “Consider the lilies in all of their loveliness, marvel at the birds of the air,” he enjoined. “Invite the little children to come to me . . . so also the beggars, lepers, and blind.”

Things matter. But in the Christian tradition we share, material things have posed a perennial problem. For instance, hoarding wealth (building extra barns to store one’s bounty) is condemned. So, also, idol worship (deifying objects fashioned by one’s hands) is forbidden. The former disrupts fidelity with our neighbors and the latter fidelity with God. To escape these perils, more than a few Christians have become functional Gnostics. They draw a bright line to separate the material from the spiritual. Simple enough in theory, but if you count on daily food and safe shelter, this binary can’t be sustained. It’s false. It’s also heresy.

Have you ever noticed how on some fleeting summer afternoon a small found thing with the barest being can, for a moment, become treasure or talisman? Or how in autumn a just-fallen oak leaf clatters down the sidewalk until the light breeze at its back becomes a great gust? That leaf and 100 brothers now caught up in a sweeping whorl. Small glories. And that light breeze, a sudden bluster. Mere things are subject to short seasons. But that is enough: mere being the seed of greatness.

Having lived with Gar in the Deanery of Nashotah House Theological Seminary for nearly seven years, the Church calendar paces your life. The Lenten season just past reminded us that we come from dust and to dust we shall return. Some of us received the cruciform mark of black ash on our foreheads. This is the Lenten labor, the emptying out, darkness pending, kenosis. Humbled beneath star-filled skies, the psalmist’s rhetoric obtains. What is humankind? A passing glory, except for love divine.

As you know, I too love a tidy cabin. So here is what I am thinking, Dawn. As we sweep out bits of bark and dead moths, so also let’s fill the dust bin with meta, mega, and maga. Treasure Basil’s pinecones (for a while), rescue any Dave Brubeck CDs lying about, and I will join you in holding fast to all that is mere.

With affection,

Cam

Notes:

[*] It is unusual for me to write in epistolary form, but in this case it seemed appropriate given my musings and the topic. This same format is one that colleague and dear friend Bruce Herman expertly employs in his forthcoming book Makers by Nature (IVP Academic). I have read some early chapters and am eager to have an actual copy in hand.

[1] Daniel Colin, “Remains of an Ancient Feast.”

[2] Peter Korn, Why We Make Things and Why It Matters: The Education of a Craftsman (Boston: David R. Godine, 2015), 65.

[3] Christian Wiman, Zero at the Bone: Fifty Entries Against Despair (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2023), 30.